Main Line payday lender Hallinan may have to forfeit $491M

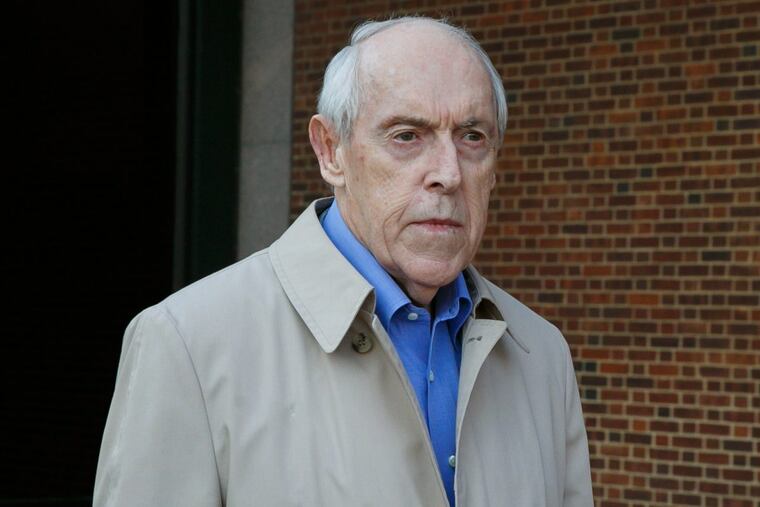

Federal prosecutors in Philadelphia hope to recoup more than $491 million from Charles M. Hallinan, the so-called "godfather of payday lending," next month in one of the largest criminal forfeiture proceedings ever in the Philadelphia region.

How much should a racketeering conviction cost a man who for years flouted state laws and preyed upon cash-strapped Americans to build one of the nation's largest illegal payday-lending empires?

More than $491 million, if the government has its way.

That's the sum federal prosecutors in Philadelphia hope to recoup next month from Charles M. Hallinan, the so-called godfather of payday lending, in one of the region's largest criminal forfeiture proceedings.

In addition to cash from 18 bank accounts – including more than $484,000 from Hallinan's personal coffers – the government has laid out a staggering wish list of additional items to forfeit.

Among them: Hallinan's $2.75 million lakefront condo in Boca Raton, Fla.; his family's $1.8 million, 8,000-square-foot home in Villanova; and a small fleet of luxury vehicles including a $142,000 Bentley Flying Spur.

But a month after a federal jury convicted the 76-year-old former investment banker and Wharton grad on 17 counts including conspiracy, international money laundering, and fraud, Hallinan's lawyer says it is the prosecutors who now are driven by greed.

Defense attorney Edwin Jacobs is expected to argue at forfeiture proceedings before U.S. District Judge Eduardo Robreno in the new year that a more appropriate figure, taking into account Hallinan's business expenses, would be closer to $9.5 million – roughly 2 percent of what prosecutors are seeking.

"A forfeiture judgment which exceeds $450 million would be … grossly disproportionate to the offense committed," Jacobs wrote in court filings earlier this month.

Federal law requires prosecutors to seek forfeiture in racketeering cases like Hallinan's in order to financially penalize wrongdoers and to lessen the economic power of organized crime. The RICO forfeiture statutes are especially sweeping, allowing the government to seize any money or property derived directly or indirectly from a criminal enterprise.

Traditionally, those laws have been used to strike back at the financial clout of the Mafia or large drug-trafficking organizations.

But Hallinan's case is one of a handful brought by the Justice Department in recent years to apply the same thinking to large-scale payday lending operations. Prosecutors have successfully argued that there is little difference between the exorbitant fees charged by money-lending mobsters and the annual interest rates approaching 800 percent that are standard across much of the payday lending industry.

"When crimes are motivated by a desire to make money, the criminal committing those crimes should be deprived of the proceeds of his or her crimes," Assistant U.S. Attorneys Sarah L. Grieb and Maria M. Carrillo wrote in court papers this month.

In Hallinan's case, jurors concluded in November that he made millions by illegally offering low-dollar, high-interest loans to financially desperate borrowers with limited access to more traditional lines of credit. Interest rates on many of the loans he issued ran far in excess of rate caps instituted by the states in which borrowers lived, like Pennsylvania, which imposes a 6 percent annual limit.

Hallinan entered the industry in the 1990s with $120 million after selling a landfill company, offering payday loans by phone and fax. He quickly built an empire of dozens of companies offering quick cash under names like "Tele-Ca$h," "Instant Cash USA," and "Your Fast Payday," and originated many of the strategies to dodge regulations that were widely copied across the industry.

As lawmakers in dozens of states sought to crack down on exorbitant fees charged by payday lenders, Hallinan instituted sham partnerships with licensed banks and American Indian tribes to serve as fronts for his businesses.

In all, prosecutors concluded, Hallinan's Bala Cynwyd-based lending empire brought in more than $491 million between 2008 and 2013, the period covered by his indictment.

They now say they are entitled to every penny.

Hallinan "collect[ed] hundreds of millions of dollars in unlawful debt … knowing that these businesses were unlawful, and all the while devising schemes to evade the law," Grieb and Carrillo wrote.

But Jacobs maintains that the government has willfully misinterpreted how both Hallinan's business and racketeering forfeiture laws work. Although he does not dispute the gross revenue brought in by his client's companies, the lawyer argues that the vast majority of that total was Hallinan's own money paid back to him after it had been lent out to borrowers.

Forfeiture laws, he argued in a recent court filing, only allow prosecutors to seize the financial gains a convicted racketeer made through their criminal acts – a figure, that in Hallinan's case, Jacobs puts at just under $69 million.

When legitimate business expenses like advertising, promotion, and lead generation are taken into account, Hallinan's profit margin was closer to $9.5 million, Jacobs wrote. What's more, he argued, the government has failed to consider that many of the loans Hallinan issued were entirely legitimate and issued to borrowers in states without the usury laws that prosecutors used to convict him.

"The central issue before the court is whether direct expenses are properly deductible for the purposes of calculating [criminal] proceeds," Jacobs wrote, "or whether the court should adopt the government's figure … without taking into consideration any expenses whatsoever."

Still, the $491 million bill the government is issuing to Hallinan is not even close to the largest sum Justice Department lawyers are seeking to forfeit in its string of cases against payday lenders. That distinction belongs to the $2 billion that prosecutors in Manhattan hope to wring from Scott Tucker, a professional race car driver and former business partner of Hallinan's who was convicted in October on a similar racketeering indictment.

Their list of forfeitable property in that case includes six Ferraris, four Porsches, and a Model 60 Learjet.

Others convicted in payday lending cases face substantial potential penalties. Jenkintown lender Adrian Rubin, a former Hallinan partner who pleaded guilty to racketeering charges in Philadelphia in 2015, faces potential forfeiture of $7.5 million. Prosecutors hope to take $161 million from Richard Moseley Sr., a lender convicted in Manhattan just 12 days before Hallinan.

And Hallinan's longtime lawyer, Wheeler K. Neff, of Wilmington, who was tried alongside him and convicted of devising many of the faulty legal strategies that allowed Hallinan's businesses to continue to rake in profits – faces his own potential forfeiture bill of more than $360,000.

Like Hallinan, Neff and the other lenders could be ordered to pay additional penalties in the form of fines and court-ordered restitution to victims.

Hallinan faces a possible decade in prison or more at a sentencing hearing scheduled for April.