Chinese come to Philly to learn the logic of our legal system

A masters of law degree brings Chinese lawyers and prosecutors to Philadelphia

Sun Liting traveled all the way from northeast China to North Philadelphia, only to find herself being questioned on the witness stand — of a Temple University law class.

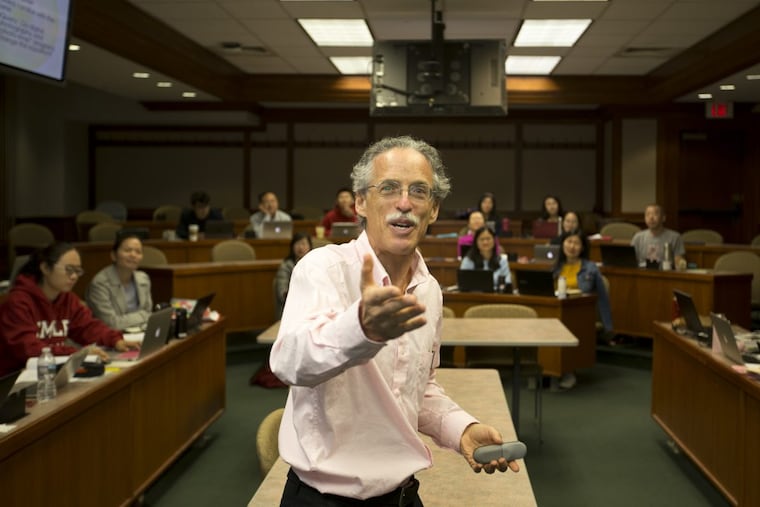

"What is this?" professor Jules Epstein demanded, brandishing a small dark tablet.

"It's a notebook," Sun answered.

"Whose notebook is it?" he asked.

"It's mine."

"How do you know it's yours?" Epstein persisted.

"It has my name on it!" Sun exclaimed, as her classmates broke up in laughter.

Those five minutes on the stand provided a nervy, personal lesson in the concept of authentication — that is, the legal method of proving that a piece of physical evidence is genuine. It was part of an ongoing summer's worth of instruction for 45 Chinese lawyers, legal aides, prosecutors, judges and students, here to learn about that baffling and ever-shifting beast known as the American legal system.

East meets West? No. More like East meets Boston Legal. With a dash of To Kill a Mockingbird.

At home, the students work in a legal system where the right to remain silent is a foreign concept, and lawyers who take on unpopular causes can wind up in jail. In 2015 nearly 250 lawyers, aides, and activists were taken into custody during a nationwide crackdown, according to Amnesty International.

At the same time, before anyone starts pointing fingers, consider the city where they're studying American law: Philadelphia, where the top law-enforcement official is under federal indictment, and judges have been sent to jail for fixing cases.

"I'm not trying to give them a perspective that the U.S. justice system is the right system, or the best system, or better than China's," said Sara Jacobson, the director of Temple Law School trial advocacy and an associate professor of law. "I want them to see — and draw their own conclusions."

That visual examination includes on-site visits to local criminal court, federal immigration court and the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington.

"It gives me a lot of inspiration," Sun said of her Temple learning.

She's 30, for five years a province-level prosecutor in Jilin, which borders North Korea and Russia and is known for its bitter winters. More than half the students are women, and most are in their 30s.

They are working toward a master of laws degree, known as an LL.M., in a collaboration between Temple and the law school at Tsinghua University in Beijing. They spend two months in Philadelphia as part of their learning.

Temple is known for producing skilled trial advocates, and that's a big part of the instruction — the thrust and parry of direct and cross-examination, the framing of questions and arguments, the outlines and headlines of forming a case. In classes, students take on the roles of witnesses and lawyers in cases as generic as an apartment robbery and as specific as a bicycle accident on Montgomery Avenue in Elkins Park.

"I learned a lot," said Lei Tian, 35, an in-house, Beijing-based counsel to a Danish pharmaceutical company.

Classes are taught in English, requiring students to understand not just everyday conversation, but the nuances of complicated legal concepts. Not everything translates. The word "sequester" is a stumper.

Oversized cherry-and-white Temple sweatshirts are the standard uniform.

In China, the classmates hold all kinds of legal jobs.

Yachao Hao is a partner in a Beijing firm that has branch offices from Shanghai to Silicon Valley. Yan Guo directs the Division of Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters for the Chinese Ministry of Justice.

Here on the streets of the United States, they worry about crime. And shootings. People in China are forbidden to own firearms. Few of the students venture outside at night.

"They're smart as whips," Epstein said.

He, too, found himself on the witness stand last week, portraying the victim of a bicycle accident near the Creekside Coop in Elkins Park.

Wang Sui, a 30-year-old prosecutor from Jiangxi Province, wanted to show Epstein a map of the area where the mock accident occurred, but first had to move through the laborious American process of introducing evidence.

She marked the exhibit, showed it to a pretend opposing council, asked an invisible judge whether she could approach the witness, presented him the map, and sought to have it admitted into evidence.

Then, finally, a question:

"Can you look at this map and show me where the food store is located?"

He could.

Introduction complete. And lesson learned.

"I'm here to learn about evidence," Wang said, "to do a better job."