A story of Pa. casinos, corruption and the greatest mobster you've never heard of

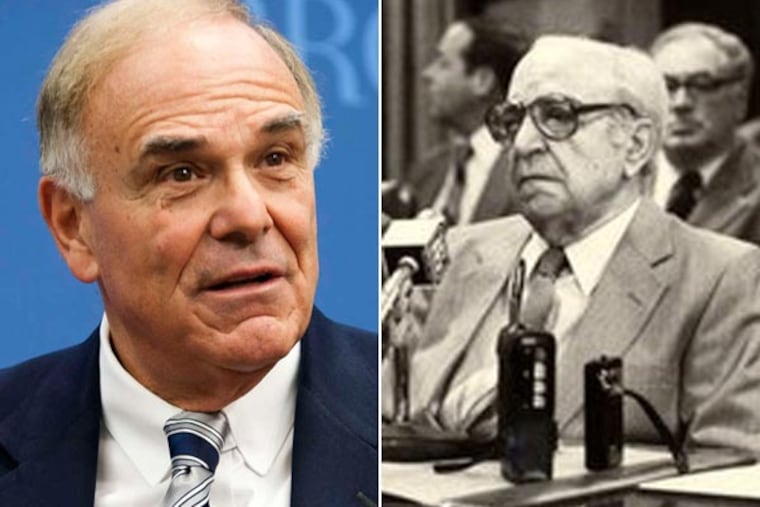

In "The Quiet Don," Matt Birkbeck weaves together the stories of two of the most powerful men to emerge from Pennsylvania in the late 20th century.

Firstly, it's a gripping biography of the little-known Russell Bufalino, a crime boss with the uncanny ability to pop up, like a malevolent Forrest Gump, at crucial moments during post-World World II history.

It's also the near-fantastical tale of how Gov. Ed Rendell pushed through legalized gambling in the state, allegedly steering contracts to favored campaign contributors and derailing state police efforts to investigate mob-tainted applicants for casino licenses. (Read Chapter One of the book here.)

Close followers of La Cosa Nostra may recognize Bufalino's name. Up until now, the mild-mannered mobster, who died in 1994, was best known for racketeering in the northeast part of the state. But Birkbeck, after years of poring through reams of legal documents and conducting dozens of interviews with those close to Bufalino, paints a revelatory picture of the man.

Birkbeck says it was Bufalino who organized the first big get-together of the La Cosa Nostra crime bosses at Apalachin, N.Y. in 1957. The book also says Bufalino participated as a mob representative in the botched Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1963; collaborated with the CIA in a plot to assassinate Fidel Castro; and ordered the hit on the Teamsters' Jimmy Hoffa because of concerns the one-time union kingpin might spill details of his involvement in the Castro plot.

Birkbeck finds a link between Bufalino and Rendell through the influential Scranton businessman Louis DeNaples, who escaped a conviction on a federal fraud charge after one of Bufalino's henchmen bought off a juror with $1,000 and a set of car tires. DeNaples, Birkbeck alleges, was initially granted a casino license to operate a slots parlor in the Poconos after corralling business associates to donate $600,000 to Rendell's campaign coffers.

Rendell did not immediately respond to a Philly.com request for comment on the allegations. In an interview with the Allentown Morning Call last month, Rendell said he was not part of the Gaming Board's decision-making process and told his appointees to pick the best candidates for gaming licenses.

Philly.com spoke with Birkbeck a few days before the Oct. 1 publication of "The Quiet Don: The Untold Story of Mafia Kingpin Russell Bufalino" (Penguin).

Q: Where does Rosario "Russell" Bufalino rank in the pantheon of major mob figures?

Birkbeck: He's clearly one of the top five mobsters in the history of the Mafia in the U.S. Given the influence he had in the Teamsters Union, the garment industry, local and national politics - he had deep ties to senators and state representatives. What you need to realize is that even though he was from Kingston near Scranton, he spent three or four days every week in New York City conducting business. From there he'd be going back and forth to Philadelphia, Florida, and Cuba. Given his very lengthy career, and who he mentored under (the ruthless crime lord, Stefano Magaddino in Buffalo), he ranks close to the top, which is remarkable because people don't know who the heck he is.

Q: So why isn't Bufalino a household name?

Birkbeck: Bufalino learned his craft under Magaddino, who was bootlegging and bringing in booze from Canada during Prohibition.

What Russell learned from Magaddino was the art of remaining in the shadows. You don't wear the fancy silk clothing, live in a big home, buy the nicest cars. At the same time you establish connections with local media and law enforcement so you'll rarely see your name in the newspaper or get in trouble. That's how Russell lived as an adult as he was building his empire.

Since he lived in Kingston, he was a long way from the major media centers. He may have been noticed every now and then. In the early 1960s he was described by a U.S. Senate committee as one of the most violent and influential members of the mob in the country. But because he was from the Scranton area he wasn't even a blip on the radar. He was able to operate in a vacuum and flew most of his life under the radar.

Q: How did you first learn about Russell Bufalino?

Birkbeck: When I was covering the Louis DeNaples trial for the Morning Call I'd written a number of investigative pieces. We had pretty much led the reporting on the gaming fiasco and during that lengthy reporting I had developed a number of sources. Ralph Periandi, the former deputy commissioner of the State Police, had contacted me right after the grand jury had begun its investigation. I had also developed contacts in the Bufalino family and they helped ID people who were testifying at the grand jury. Once (Scranton businessman and Pennsylvania powerbroker) Louis DeNaples and Father Sica were indicted I had developed other contacts.

I had not known about Bufalino until the DeNaples indictment. His name kept popping up. Then I was thinking, who is this Bufalino? I started doing some digging. I FOIA'd his FBI file, dug into senate and house organized crime investigations and the house and senate assassination reports from the 1970s. As I'm going through it, I came across the New York state attorney general's report on the Apalachin Mafia summit.

When you dig into thousands of pieces of paper it's tedious at times, but the nuggets started to pop out - names I'd previously covered, their fathers, other family members. You start seeing this information about Russell Bufalino and who he was with. In one instance, the FBI had Russell with (Angelo) Bruno in Philadelphia. According to the FBI, it wasn't Russell who was paying homage to Bruno, it was Bruno who was always deferential to Bufalino. The same thing in New York. Russell had a restaurant in the city, the Vesuvius, and New York mob guys would be seen going in there. It was the mob guys who were always paying homage to Russell. That speaks volumes.

When you go through the Apalachin report, you learn it was Russell who organized (the historic 1957 mob summit). When Russell was caught by police leaving the meeting he was with (New York City mob boss) Vito Genovese. Apalachin was the famous meeting that introduced the Mafia to America. (The meeting was called because Genovese was behind the assassination of Albert Anastasia and he wanted to broker a peace between the crime families.)

It all started to come together. Then I found people who knew Russell and did business with him. They confirmed certain other allegations, particularly Russell's involvement in the Hoffa killing, but now I knew the real reason why. I was getting this picture of this mob leader who was far more powerful than anyone ever imagined.

I was reading old FBI reports about Russell's cousin William in Detroit - he went out there out of the blue to work with Jimmy Hoffa and do some business with juke boxes, and then later became the chief counsel for the Teamsters under Hoffa.

That didn't just happen accidentally. That had been planned out, by Russell. All those pieces came together. It became a remarkable story about one of the most powerful people in the country who, at any given time, could use his immense power with Hoffa and the Teamsters and bring the country to its knees.

Q: In the book you reveal that it was Russell Bufalino who ordered the killing of Jimmy Hoffa. How did you learn that?

Birkbeck: Frank Sheeran (a labor union official and mob hit man) worked for Russell. He claimed later he shot Jimmy Hoffa under orders from Bufalino. But the problem was there was no one else who supported his story. Then I hear that Russell had a friendship with Batista, the Cuban dictator. They were so close that Batista would send his kids to the Poconos for the summer to vacation under Bufalino's protection.

I learned that Frank Sheeran's claim that he killed Hoffa under orders from Russell was true. Sheeran was a dark figure, he killed dozens of people, many under Russell's orders. But Sheeran claimed the reason why (Hoffa was hit) was there was so much pressure on Russell from other mobsters to OK an execution on Hoffa, because Hoffa was seeking to regain the presidency of the Teamsters. They were afraid if Hoffa didn't get his way he would spill all their secrets. Russell and Hoffa were very good friends. Russell never for once believed Hoffa would ever talk. He thought Hoffa was just blowing off steam.

Then the Time magazine article came out about the Senate Committee's investigation of the CIA/Mafia plots. The Church Committee was looking at the Agency's plots to depose foreign leaders, including Fidel Castro, and Time magazine identified Russell and three other mobsters as being involved in the plot to assassinate Fidel Castro.

Russell was very publicity-shy. After the story ran, he quickly took action. There were three remaining mob figures who were part of the CIA plots, (Chicago mob boss Sam) Giancana, Hoffa and (Los Angeles mob kingpin, "Handsome Johnny") Roselli. Giancana dies in 10 days. Hoffa disappeared in six weeks. And Roselli was tortured and murdered the following summer.

The FBI, after investigating Hoffa's disappearance for a year, circled around six suspects and two of them were Bufalino and Sheeran but they could never get one to flip on the other. They ended up going after them for other crimes.

A lead prosecutor in a subsequent Bufalino trial in another case said to me that Russell had a favorite saying that he had inscribed on a plaque: "There is no conspiracy when only one remains."

Q: Russell Bufalino was involved with the disastrous 1961 invasion of Cuba. How did that come to pass?

Birkbeck: Bufalino felt burned by Castro. The mafia enjoyed a very close relationship with Batista, the Cuban dictator. That's been well-documented. The mob built these great hotels. Havana was the Las Vegas of the 1950s. It was a cash cow. They were practically printing money there. Fidel Castro had apparently told them he would not close the casinos when he came to power. Russell worked out a deal with him. They were running guns to Batista, and when that tide turned they hedged their bets and sent guns to Castro. Some of this is in the FBI files. Castro later reneged on the deal and kicked them off the island. So a huge cash stream was cut off.

Jimmy Hoffa was the one who had mob contacts. The CIA reached out to him. Someone there came up with the brainstorm, l bet we can get some mob guys to help us out there. But after they botched the Bay of Pigs invasion, the anger went from being directed at Castro to being directed at Kennedy.

But I purposely didn't address Russell's possible involvement in the Kennedy assassination. Maybe there's something to it. He was furious after the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Q: How did you start investigating corruption in Pennsylvania gaming?

Birkbeck: As I said, I was following the DeNaples investigation while I was working with the Morning Call. When he applied for a casino license it was questionable from Day 1. I knew several state representatives and they were complaining to me and they were telling me how this vote to approve the casino legislation took place on July 4, 2004 and it was forced on them. Initially it was a small bill, 37 words, with no mention of slots. Suddenly, it was 140 pages long.

(The law, which was labeled the Pennsylvania Race Horse Development Act, referred to commonly as Act 71).

In most states, including Nevada and New Jersey, if you're a convicted felon you can't be part of the gaming industry. DeNaples had pleaded no contest in 1978 to defrauding the federal government of $525,000. That was after his first trial was fixed by James Osticco, who was Russell Bufalino's underboss. Conveniently for DeNaples, someone put in a 15-year rule which meant he could apply for a gaming license.

Immediately after the legislation was approved, DeNaples announced he was buying Mount Airy Resort to build a casino, so clearly something was up.

Through the years, Pennsylvania had tried to introduce gaming to the state starting in the late '60s. Every time there was a referendum Pennsylvania voters would say "no." Those referendums were usually prompted by owners of the Pocono resort hotels and many of those resorts had mob ties.

The one thing I found at the time that was mind boggling: The amount of money that was going to Ed Rendell from people associated with DeNaples. DeNaples himself was barred from contributing, but there were people associated with him who out-of-the-blue were kicking in $50,000 to $100,000 to Rendell. From a handful of DeNaples's friends, Rendell got over $600,000. There was clearly a flow of money going to Rendell at the time.

When he first ran for Governor, Rendell sold this casino law as a cure for rising real estate taxes. That's how this thing was sold to the public. That was the lure. But my taxes haven't gone down, not significantly anyway. Have yours? It was a scam from Day One.

Contact Sam Wood at 215 854 2796 or samwood@phillynews.com