Vets frustrated by the way the city treats their fallen friends

Vietnam veteran Ari Merretazon was on a mission last week when he went to City Hall: Find the gravesites of his war buddies Carl Brabham, Tyrone Green, and Bobby Williams.

At a first-floor office called the Veterans Advisory Commission, he was directed to a table covered by dusty shoeboxes crammed with scores of burial records dating back decades. Some of the faded index cards were alphabetized, some were not. Some were organized by year, others were in a jumble.

No luck.

Then he asked Scott Brown, the office's director, to look up the three fallen friends on a computer. Each search ended with Brown shaking his head and quietly announcing he'd found nothing.

It's not the first time Merretazon has looked in vain for the resting place of Williams, a soldier he served with in 1967 and 1968.

"I couldn't even find his gravesite to pay homage to him," Merretazon said. "My heart is broken. This guy saved my life on several occasions, as I did his."

According to state law, each of Pennsylvania's 67 counties is required to account for the burial places of veterans — it's called the Veterans' Grave Registration Record. The records are public and open to inspection during business hours, according to the law.

Officials from Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery Counties said they maintain such public records as the law requires.

The city has made strides to serve its veterans, says Jane Roh, spokeswoman for City Council President Darrell L. Clarke, whose office oversees and funds the advisory commission. When Clarke became Council president, he moved the commission to a first-floor office, and has increased its personnel and funding. Before 2012 it had a single staffer.

But compliance with the records law remains a work in progress.

"Dirty, raggedy boxes with cards in them, all scattered," Merretazon said, shaking his head in disgust after leaving Brown's office. "It's embarrassing to the city, it's totally disrespectful to the veterans who served this country."

Brown, who has held his job since 2014, referred Merretazon and a reporter to Roh for comment. "If the records are incomplete, that happens. It is government," she said.

But it's not supposed to happen, and it's not happening in neighboring counties.

"I deserve this, my brothers deserve this," said Lawrence Davidson, Chester County director of veterans affairs. "I think it's a big deal."

"We just want to have accountability of where these folks are," said Sean Halbom, director of veterans affairs for Montgomery County, which, like Chester County, is computerizing its burial records.

A statement from Clarke's office said that he was aware of the grave registry backlog and had directed the commission to make complete recordkeeping a priority.

"Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for city employees to discover misfiled or misplaced records of all kinds in offices throughout City Hall," the statement read, adding that the commission had enlisted the help of volunteer veterans and Project HOME. "Council President Clarke is deeply sympathetic to those who are personally affected by the city's incomplete record-keeping, and is committed to doing better by those who have served our country."

For Merretazon, the spotty records speak to a lack of respect. He is 69, a leader of the Pointman Soldiers Heart Ministry, a religious-based veterans group. The Wyncote resident was born Haywood T. Kirkland in South Carolina and raised in Washington. He moved here in 1997. His experiences in the military and afterward partly inspired the 1995 movie Dead Presidents, about a group of black Vietnam veterans who steal worn-out federal currency from a mail truck.

At Virginia's Lorton correctional facility, where he served 5½ years for armed robbery and kidnapping, he became a leader of fellow inmates. Ultimately he would testify before Congress on the plight of incarcerated Vietnam vets and meet with former President Jimmy Carter.

He and another member from his veterans group are suing City Council over the records and contending that the advisory commission falls short of a full-blown Office of Veterans Affairs, which state law requires each county to have. Merretazon had previously applied to lead veterans services for the city.

The city says the suit is without merit.

Joseph Butera, spokesman for the Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans Affairs, said Philadelphia's Veterans Advisory Commission qualifies as a state-mandated department of veterans affairs.

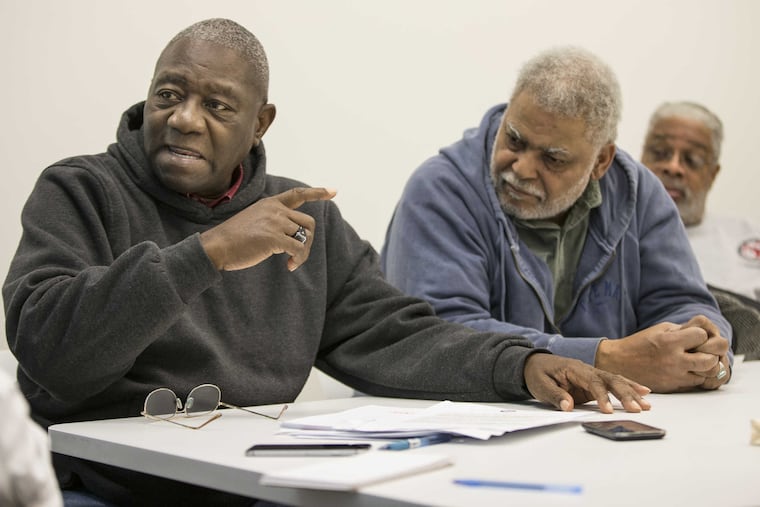

The Pointmen group, most of them Vietnam vets, seethe and tear up when speaking about their struggles with the city. They complained in an interview that the Veterans Advisory Commission is not effective in helping them get benefits from the federal Department of Veterans Affairs.

"We got families, we work, we've retired from jobs and done things for this country, and for Philadelphia to sit on their [behinds] like we don't exist...," said Vietnam veteran Reginald Strange, 71. "I'm almost ashamed to be a citizen here."

Charles Levere Sr., 70, who served in the Army's 25th Infantry Division during the Vietnam War, said: "I remember when I first applied for my benefits. They told me I was dead. I got a letter: 'Fill out the death certificate and send it in and we'll see if he's entitled to benefits.' Damn!"

Fellow Vietnam veteran Dwight James said that just two years ago, he started getting correspondence from the VA informing him that he did not serve in the Air Force. "I got back letters that I never existed. I said, this is unreal. This is when I came upon Mr. Abram," he said, referring to Pointman Soldiers president James Abram, 71, who served in Vietnam in 1966-67 but endured nearly 30 years trying to convince the VA that he served in combat.

"Look, bro, I came home from Vietnam with a rash over my whole body and with a 10 percent profile – disability. But yet, I wasn't in Vietnam," Abram said incredulously.

Merretazon said these examples of shoddy VA service are evidence that the city's veterans office is not doing its job.

Added James: "There are a lot of veterans who need help and we have been denied for so long. The city should be a liaison between the VA and the soldiers, but they are not. That's why so many veterans are dying. My brother was a veteran – he's dead. My good friends are veterans – they're dead. They never were served by the VA. Why is it that we served our country, protected our country, but come back here and fight the real war?"