This Congress has been mired in inaction

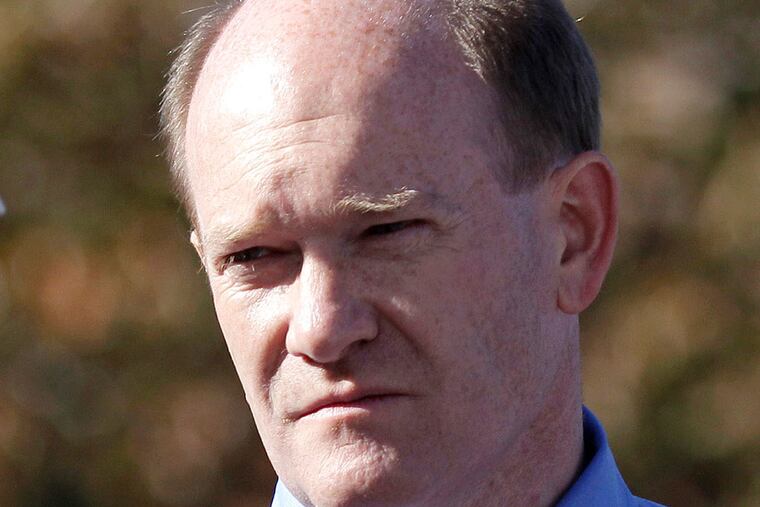

WASHINGTON - Early into his tenure in a rancorous Congress, Sen. Chris Coons (D., Del.) asked the chamber's longest-serving member, Patrick Leahy, if things had ever been this bad before.

WASHINGTON - Early into his tenure in a rancorous Congress, Sen. Chris Coons (D., Del.) asked the chamber's longest-serving member, Patrick Leahy, if things had ever been this bad before.

Yes, said Leahy, a Vermont Democrat who has been in the Senate since 1975.

When? Coons wondered.

"Well, there was that Civil War," Leahy replied, according to Coons.

The younger Democrat, a former county official in Delaware with a wry sense of humor and disarming honesty, told the story with a laugh.

But sitting with reporters in July, as Congress sped toward summer vacation, Coons, 50, also hinted at dire long-term consequences if Congress can't get past the infighting that has made for months of sputtering inaction.

In another conversation, one "very conservative" Republican, Coons said, worried that this might be the last functional Congress.

"Given the reputation we're developing as a place where nothing happens except filibusters and shutdowns, the only people who are going to want to come here are ideologues or hacks," said Coons, a freshman senator. "That's not a very compelling vision."

Congress' impotence has been underscored by a series of crises: thousands of Central American children arriving at the border, a Syrian civil war, Iran's nuclear ambitions, fighting in Gaza and Ukraine.

Lawmakers and President Obama have seemed like characters in old episodes of Star Trek: haplessly flung from side to side by outside forces more powerful than anything they can muster.

Last week's final days of work before a five-week summer break won't change the perception Congress earned over months of procedural brushfires, a government shutdown, political messaging, and general legislative misery.

On Wednesday, House Republicans voted to sue Obama for overstepping his authority, reflecting the acrimony in Washington, and deepening it.

Rep. Bill Pascrell (D., N.J.) said Congress has "a lower approval rating than head lice."

The next two days were a picture of discord.

With a humanitarian crisis building on the border, Congress opted for the worst of possible solutions, either on the right or left: nothing.

The Senate and House put up proposals, but neither pretended their bills could become law, because there was no hint of compromise with the other side.

Instead, both parties covered their political flanks with show votes and scrambled for the exits.

Obama now expects to run short of the resources needed to handle the young migrants this summer. Congress can't approve more money until it returns Sept. 8.

Even on urgent domestic issues - addressing the veterans' care crisis and keeping highway projects rolling - it took last-minute breakthroughs to pass plans that are either obviously popular or routine.

This Congress has passed fewer substantive bills in its first 19 months than any other in the last 20 years, according to the Pew Research Center.

(The count doesn't include the last-minute action Thursday and Friday, but even with those measures, this Congress lags behind most recent sessions.)

Behind the numbers is a toxic atmosphere.

In the House, the GOP's most conservative bloc has repeatedly seized control from more centrist leaders, forcing legislation farther right (and away from the middle ground), derailing critical bills, stifling debate on a bipartisan immigration-reform bill passed by the Senate, and bringing on last fall's government shutdown.

On Thursday, conservatives stalled a border bill that had support from more moderate Republicans, then reshaped it.

"Why are we having difficulty getting things done?" Coons asked: "Because there is a war within the Republican Party between two wings, one of which is opposed to the fundamental enterprise of the federal government, and the other of which wants to work with Democrats to get things done but is afraid of the electoral consequences."

Of course, Senate Republicans say Democrats have choked off compromise in the "world's greatest deliberative body."

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D., Nev.) has unilaterally blocked GOP amendments, allowing only 10 to get a vote this year in a body that is supposed to give the minority a say.

When Sen. Pat Toomey (R., Pa.) finally got a vote last week on his transportation bill amendment, he said, "At least on this bill, the Senate is functioning." The second-longest-serving senator, Orrin Hatch (R., Utah), has decried the institution's deterioration.

"In my 38 years of service in this body, I have never seen it weaker than it is today," Hatch said Thursday in a floor speech. "The majority today has engaged in this hostile takeover of the Senate for one simple reason: aggrandizing power."

(Democrats, in turn, say Republicans have abused the Senate's minority rights by threatening filibusters and requiring 60 votes on nearly every bill.)

Fueling the fight is deep animosity between Reid and the Senate's top Republican, Mitch McConnell of Kentucky. Neither will permit the other even a small victory, the Washington Post reported.

The Senate's narrow divide means party leaders have been driven by the political aims of either taking or holding the Senate, Coons said.

"There are many senators, both relatively new and seasoned, who are frustrated by this," he said, "and who think our job is to take tough votes and to legislate." So they try to fend off gloom by rejoicing in small victories (a job-skills bill, passed, 95-3, and signed by Obama, for example) and drawing up bipartisan amendments, no matter how small, "just to keep our chins off the table," Coons said.

But no one expects significant lawmaking until after Election Day.

Then comes a test: With the races over, does partisanship ebb? Or will the political artillery just turn to the next target?

"That is the question," Coons said. "Whether in January of 2015 we begin the 2016 elections, or whether we have a period when we actually legislate."

@JonathanTamari