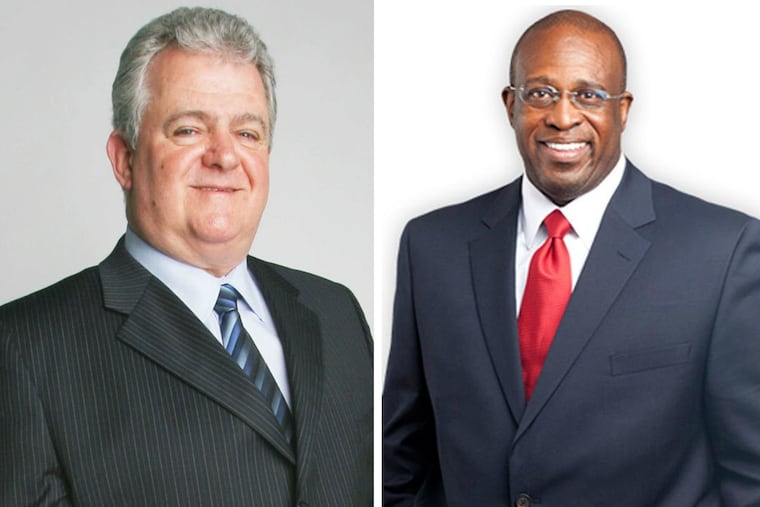

Need a job? Bob Brady and the art of the political buyout

Prosecutors' allegations last week that U.S. Rep. Robert Brady's 2012 campaign paid a challenger $90,000 to drop out of the race may seem like a particularly brazen power play. But it's all part of the art of the political buyout - sometimes illegal, sometimes just politics.

In Philadelphia, a mayoral candidate dropped out of the race, handed his campaign operation to the eventual winner, and later landed a lucrative no-bid contract from the administration.

In New Jersey, a Democratic governor appointed a Republican senator to a government agency, helping flip Senate control to Democrats.

And in Virginia, Republicans persuaded a Democratic state senator to resign, dangling a lucrative job offer on a state tobacco commission and a judgeship for his daughter — and leading to a GOP takeover of the Senate.

Prosecutors' allegations last week that U.S. Rep. Robert Brady's 2012 campaign paid a challenger $90,000 to drop out of the race may seem like a particularly brazen power play. But it's all part of the art of the political buyout — sometimes illegal, sometimes just politics.

When candidates seek exit strategies or see the writing on the wall, they often seek some kind of help from the candidate they endorse. Such transactions may look like backroom dealing, but campaign-finance experts agree that the line between the simply unseemly and the outright illegal can be difficult to determine.

The losing candidate's friend might get appointed to a government board, for example. "Those discussions are not uncommon," said G. Terry Madonna, director of the Center for Politics and Public Affairs at Franklin and Marshall College.

"Sometimes you give people a job to shut him up," Madonna added. "All that stuff is commonplace."

The documents unsealed last week showed a campaign aide for Jimmie Moore, then a former municipal judge and Brady's rival in the 2012 Democratic primary, pleaded guilty to falsifying Moore's campaign-finance filings to hide the source of the $90,000 payment.

For weeks, prosecutors had sought to keep their plea deal with Moore's campaign manager, Carolyn Cavaness, under wraps, citing an alleged attempt by Brady to influence the testimony of another potential witness, whom three sources familiar with the investigation have identified as former Philadelphia Mayor W. Wilson Goode Sr. Documents say that witness brokered the 2012 meeting between Brady and Moore that led the challenger to drop out of the primary race.

Neither man has been charged with a crime. Lawyers for both say they have done nothing wrong.

Authorities have signaled that their investigation continues and have indicated in court filings that Cavaness is cooperating with the probe.

Brady's attorney, James Eisenhower, says Brady's campaign paid the $90,000 for valuable polling data and to hire Cavaness as a subcontractor.

"Rarely are these situations an explicit quid pro quo: 'I'll give you money so you'll drop out,' " said Kenneth A. Gross, who heads the political law practice of the Washington-based firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. "But there are many shades of gray. There are often agreements to help a candidate retire [campaign] debt."

Even the White House can get involved.

In the 2010 Pennsylvania Democratic primary for U.S. Senate, for example, the Obama administration dispatched former President Bill Clinton to try to persuade Rep. Joe Sestak to drop his campaign against Sen. Arlen Specter, the longtime Republican who had just switched parties to keep his seat. Clinton offered Sestak a seat on a presidential advisory board. The congressman declined the offer and defeated Specter in the primary before losing the general election.

Democrat Joe Torsella briefly ran in that same primary, dropped out early, and was later appointed by President Obama to a job at the United Nations. Torsella is now Pennsylvania state treasurer.

Political buyouts aren't limited to campaigns. Savvy operatives pull the levers of government to advance an agenda or eliminate potential threats.

In 2003, New Jersey Gov. Jim McGreevey, a Democrat, appointed Republican State Sen. John Matheussen as CEO of the Delaware River Port Authority, then a $195,000 post. State officials also ensured Matheussen would be able to stay in the New Jersey pension system, even though he was moving to a bistate agency.

The Senate was split 20-20, and Democrats won Matheussen's old seat in November to take control of the upper chamber. But it was a close race, and when it appeared to be headed for a recount, the McGreevey administration began publicly considering the Republican candidate for a judgeship.

More recently, in 2014, Virginia Republicans sank Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe's plan to expand Medicaid to 400,000 low-income individuals under the Affordable Care Act by persuading a Democratic state senator to resign and taking control of the Senate.

The GOP's leverage? A job on the state tobacco commission for the senator, Phillip Puckett, and a judgeship for his daughter.

For their part, Virginia Democrats tried to persuade the senator to keep his seat with similar enticements. Puckett resigned but withdrew his name from consideration for the tobacco job amid a public backlash.

After Puckett left the Senate, the legislature approved his daughter's appointment to the bench.

Federal prosecutors investigated the matter but did not file charges. But some think these kinds of deals are ethically dubious.

"When you talk about holding up a job that somebody might want for their livelihood as a way of getting partisan gain, that seems a little bit less like regular how-the-sausage-is-made and a little bit more like appealing to people's self-interest and material gain, which is I think more of a problem," said Noah Bookbinder, executive director of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, which tries to reduce the influence of money in politics.

Philadelphia has had its share of questionable arrangements, too.

Former City Solicitor Ken Trujillo ran a brief campaign for mayor in 2015. He endorsed then-Councilman Jim Kenney; a political action committee affiliated with Trujillo gave a research book valued at $4,200 to Kenney's campaign, as well as $10,000 to a PAC that supported Kenney; and Kenney scooped up some of Trujillo's campaign staff. Kenney entered the race shortly after Trujillo dropped out.

Last year, the Kenney administration awarded Trujillo's law firm an $800,000 no-bid contract to defend the city's sweetened-beverage tax. Mayor Kenney said at the time that the contract wasn't a political favor, calling Trujillo a "great lawyer." The mayor also said that some of the city's big law firms had conflicts of interest, and that the contract was awarded by the Law Department, not him.

Trujillo defended the contract, saying he hadn't personally contributed to Kenney's campaign.

Then there's Brady. In addition to his campaign allegedly paying his 2012 primary challenger, a former Moore supporter says Brady offered her a job to silence her.

Paula Brown, the former mayor of Darby Borough and a current candidate for that office, said she received the unexpected offer in a call from Brady in 2012, shortly after she had posted her support for Moore's campaign on Facebook.

When she declined Brady's offer, she said, the congressman pressed: Did anyone in her family need work?

"I said, 'No, everyone in my family is fine.' So I turned him down," Brown said in an interview last week.

Eisenhower, Brady's attorney, didn't dispute the phone conversation with Brown occurred but said the congressman didn't offer any jobs. He said that Brown actually apologized for having distributed Moore's petitions and that she offered to throw away those petitions and to collect signatures for Brady (the congressman said that wasn't necessary).

Told of Brady's account of their conversation, Brown laughed. "Alternative facts," she said.

— Staff writers Tricia L. Nadolny and Chris Brennan contributed to this article.

A previous version of this story incorrectly stated when Democrat Joe Torsella was appointed to a United Nations job.