How 3 Pa. towns joined forces to save money … and land

The longest operating joint zoning council in Pennsylvania, based in Bucks County, is discussing amending their agreement to prepare for the possibilities of medical marijuana growers and dispensaries and gas and oil drilling and the regulation of residents who rent their homes using Airbnb.

Towns across Pennsylvania are confronting hosts of new challenges, such as how to regulate medical-marijuana growers, oil-and-gas drilling, and residents who want to rent their homes through the Airbnb service.

What is different about three towns in Bucks County is that they are tackling these issues together. Newtown, Upper Makefield, and Wrightstown Townships, pioneers in a trend that has been slow to gain traction in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, are working up a common set of regulations to add to their joint zoning ordinance.

The concept of consolidation has been debated for over a decade in New Jersey, which some legislators and others say has way too many towns. However, Pennsylvania is far more balkanized. The Garden State's 565 municipalities have a median population of 22,000; Pennsylvania has 2,561 with a median population of 1,900, according to Census figures.

While consolidation is hardly the rage west of the Delaware River, at least a small percentage of towns are collaborating formally and informally in a key mission of local government — planning for land use and development. In all, 42 municipalities participate in 14 joint zoning ordinances, according to a survey of county planners by the state's Department of Community and Economic Development in 2015.

"It has the potential to be a really good tool, particularly in those parts of the commonwealth that are seeing a great deal of growth," such as southeastern Pennsylvania, said James Cowhey, president of the Pennsylvania chapter of the American Planning Association.

The first such agreement in the state was the Newtown Area Joint Municipal Zoning Ordinance. It covers 41 square miles of Bucks County and the 31,000 people who live in Newtown, Upper Makefield, and Wrightstown. That combined population is lower than that of 17 municipalities in Philadelphia's collar counties.

The joint council has received an environmental award from a governor and a pat on the back from the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

Why collaborate?

In the 1970s, under court orders, Upper Makefield had to create a mobile-home-park zoning district and was looking for an out-of-the-way place for it, according to Michael Frank, a retired Bucks County planner and a former consultant for the municipalities. The proposed site was on the boundary with Newtown Township, where officials objected to the potential for an increase in traffic in their town.

Officials in Upper Makefield and Newtown decided they should cooperate, Frank said, and neighbors Wrightstown and Newtown Borough joined them. The communities already shared a school district, traffic, and some commerce.

In 1983, the towns adopted a joint comprehensive plan and then a joint zoning ordinance that aimed to protect farmland and natural resources, control commercial growth, limit quarries, and preserve the region's history. They did so under the Pennsylvania Municipalities Planning Code. The key was to manage development.

How does it work?

Typically, each township, borough, and city in the state has to allow for all types of lawful zoning uses, even ones they may consider undesirable, such as junk yards. However, the planning code permits municipalities with joint zoning to act as one large municipality. Thus, not every community has to provide for all uses.

The Newtown area joint ordinance built on the strengths of the individual towns, land uses already in place, and the desires of the partners. It focused business districts and population growth in Newtown Borough and Newtown Township, which had the infrastructure to sustain it. Wrightstown already had quarries, so zoning there focused on those and light business uses. In Upper Makefield, zoning was tailored to medium- to low-density development.

The boards of supervisors of the municipalities make up the joint zoning council, which meets monthly. If members want to alter the joint zoning ordinance, each board takes the changes to its respective community and votes. Each community then uses its one vote to accept or reject the alterations at a joint council meeting. Each is responsible for enforcing the zoning districts it contains.

Chester Pogonowski, chair of the joint zoning council and of Wrightstown's board of supervisors, compared the collaboration to a family. "And sometimes the siblings of the family disagree and we may shout at one another," he said, but they are united in protecting their agreement.

What’s in it for them?

Together, the municipalities are in a stronger position to defend challenges to their zoning ordinance than they would be individually. They share the costs, with the municipality at the center of a challenge paying the majority, and the others splitting the rest.

The joint zoning council has successfully fought challenges through the years, including one by Toll Bros. and eight farmers in the Dolington Land Group. The developer wanted to build 1,200 homes in a district designated for rural residential uses in Upper Makefield and argued the zoning code did not adequately allow for new housing. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled in favor of the joint zoning ordinance and the council's practice of constantly studying and updating it at the end of 2003.

The communities also get a say in what development happens around them. A formal arrangement forces municipal officials to maintain a dialogue on all sorts of local issues.

"A lot of municipalities will put undesirable uses on their borders so the impacts affect their neighbors," said Maureen Wheatley, a senior planner for the Bucks County Planning Commission and adviser to the joint council. "These municipalities are looking beyond their borders."

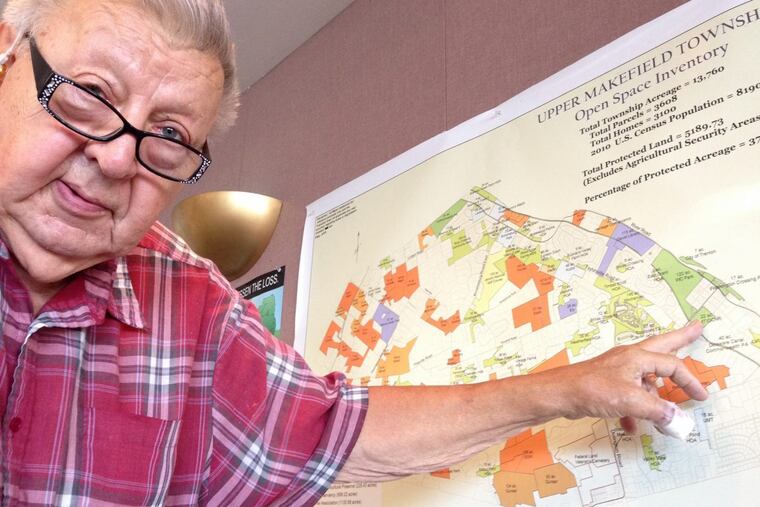

Keeping most of the growth in Newtown Township and the borough slowed sprawl; preserved more open space in more rural Wrightstown and Upper Makefield, and, according to officials in Newtown Township, saved the surrounding communities more than $30 million in costs for roads and sewer improvements.

Why doesn’t everybody do this?

"You give up a little control," said Pogonowski, joint council chair. "If Wrightstown wants to make a change, it needs to get buy-in from Upper Makefield and Newtown Township and vice versa."

Collaboration doesn't work if municipalities don't share a vision for the future of a region, if cultures clash, or if one or more of the communities does not benefit.

Newtown Borough left the joint zoning agreement in the mid-'90s. The borough, which is less than half a square mile, was mostly built out, so officials weren't worried about the future plans of developers.

"It got to the point where the other municipalities were looking toward the borough to provide greater money toward maintaining the jointure than what the borough thought was in our best interest," said Charles Swartz, the borough's mayor.

The townships still in the agreement also acknowledge changes to their joint ordinance take longer than in an individual community, since more people have to sign off on it.

At this month's meeting in Wrightstown, Pogonowski said that since no one from Upper Makefield was present, that's where the municipalities would zone for a hypothetical "adult bookstore." He was joking, of course.

But the issue of how to regulate any potential "adult entertainment" enterprise will be on the agenda for a future meeting.