Extorting sex with a badge

Hundreds of police officers across the country have turned from protectors to predators, using the power of their badge to extort sex, an Inquirer review shows. Many of those cases fit a chilling pattern: Once abusers cross the line, they attack again and again before they are caught. Often, departments miss warning signs about the behavior.

Clearing the Record

This article on police officers who extort sex gave an incorrect neighborhood for a police stop at Torresdale Avenue and Levick Street, which is in the Tacony section of the city.

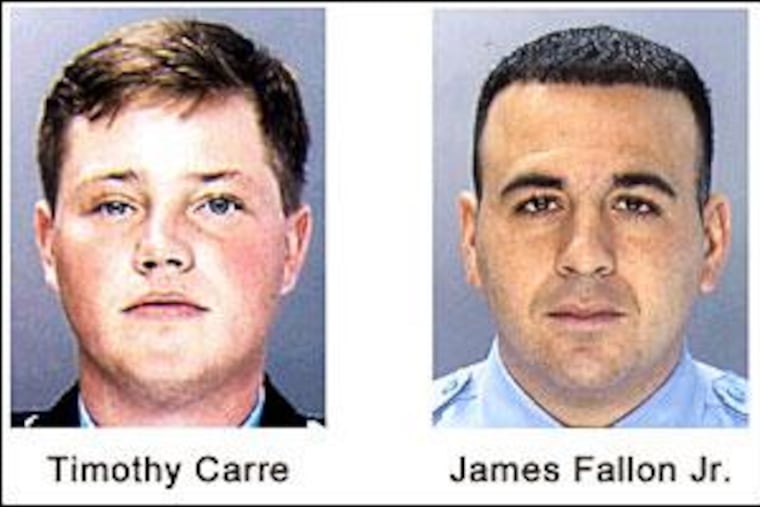

Philadelphia Police Officer James Fallon spent many midnight shifts on patrol - not for crime, but for sex.

His partner, Timothy Carre, says he tried to warn their bosses, but nobody paid attention - not until the night Fallon and Carre stopped a stripper getting off her shift, forced her into their patrol car and, she says, took turns raping her in the darkness near I-95.

The officers are now off the force, convicted of sex crimes, but the city is still confronting the consequences of that 2002 attack.

Investigators found a string of other women who say they were victimized by the pair, and a lawsuit filed by the dancer recently brought to light dozens of other accusations of sexual misconduct involving Philadelphia police from 1992 to 2002. The department dismissed most as groundless, or unprovable.

In another, still-open case obtained by The Inquirer, the department allowed an investigation into a complaint of a forced sexual display in a police lockup to languish for years. No one has been disciplined.

Philadelphia isn't unusual. Hundreds of police officers across the country have turned from protectors to predators, using the power of their badge to extort sex, an Inquirer review shows.

Many of those cases fit a chilling pattern: Once abusers cross the line, they attack again and again before they are caught. Often, departments miss warning signs about the behavior.

Most police departments do little to identify the offenders, and even less to stop them. Unlike other types of police misconduct, the abuse of police power to coerce sex is little addressed in training, and rarely tracked by police disciplinary systems.

This official neglect makes it easier for predators to escape punishment and find new victims.

Lawyers for Philadelphia's 7,000-member department say in court papers that sexual-misconduct complaints are "extremely rare" and that commanders move swiftly to discipline offenders.

Though the number of abusive officers in any one department is usually small, the damage they leave behind is often devastating - to their victims, to taxpayers and to the reputations of their colleagues.

The Inquirer found nearly 400 reports of police sexual misconduct across the country in the last five years, including dozens in the Philadelphia region:

In Baltimore last month, a detective was suspended after a 16-year-old girl picked up for prostitution said he assaulted her at a police station. Three other Baltimore officers allegedly raped a woman in a station house in December, and are facing criminal charges.

A Glenolden, Delaware County, officer was convicted of raping a woman in 2002 after he answered a domestic-dispute call. "He had his police uniform on, his gun, his nightstick," the woman said. "I did exactly what he asked me to do."

In small-town Edgewater Park, Burlington County, a police officer bought a Burger King meal for a female prisoner in 2002 - then forced her to have sex in a police van. He went to jail.

A San Bernadino, Calif., officer preyed on prostitutes and drug addicts, attacking them in dark lots or abandoned buildings. By 2003, the city had paid a total of $300,000 to 18 victims. "I was scared beyond speech," said one woman who was raped by the officer while handcuffed.

The abusive officers who are caught and charged are likely only a fraction of the real number, policing experts say.

Many victims, ashamed and intimidated, never report the crimes, The Inquirer review shows. As in the case of Fallon and Carre, victims often don't surface until the offenders are caught and taken off the street.

"The women are terrified," said Penny Harrington, the former police chief of Portland, Ore., and founder of the National Center for Women and Policing. "Who are they going to call? It's the police who are abusing them."

When women do come forward, their complaints are often ignored.

Indeed, experts say, culprits tend to target vulnerable women such as prostitutes, drug addicts or drunks, knowing they likely won't be believed.

"You don't pick the mother of three, the soccer mom. You don't pick the prom queen," a prosecutor said during a 1997 trial of a Norristown police officer convicted of sexual assault.

"You pick the delinquent kid. You pick one of the street crawlers, people out there at 4 in the morning."

The extent of the problem remains concealed from the public - and police chiefs - because departments often lump sex-abuse allegations into such categories as "conduct unbecoming."

In one study, researchers dug into case files in Florida and found that when police abused citizens, sexual abuse was the most common violation.

In Pennsylvania and New Jersey, where complaints against police remain shrouded in secrecy, those statistics aren't available.

Other than the cases released as a result of the lawsuit, the city won't disclose any other sexual-misconduct complaints, and won't say whether any sexual allegations are currently under investigation.

Police Commissioner Sylvester M. Johnson, citing the suit, wouldn't discuss how the department handles sexual abuse by police.

"He doesn't want to talk about it," said Capt. Benjamin Naish, a police spokesman.

'Deal with it'

Timothy Carre says he told his bosses more than once that his partner, Fallon, was abusive toward women and obsessed with sex on the job.

"All he wants to do is f- and sleep," he says he told supervisors. Their response: "Deal with it," he said.

Carre, 32, declined to talk to The Inquirer. His account comes from lawsuit depositions and from someone familiar with his version of events.

In the three months they were partners in Northeast Philadelphia in 2002, Carre says, Fallon's behavior toward women left him cringing.

In interviews with The Inquirer, Fallon, 36, conceded that he'd had sex on duty, but claimed that he never harassed or assaulted anyone.

"Don't get me wrong, I wasn't an angel," Fallon said, adding that he is now faithful to his wife. "You've seen the pictures of me... . I'm built. I work out five days a week. I was a Marine. I'm the pretty boy. I have the image."

Fallon now claims that the dancer voluntarily had sex with him and Carre and that he pleaded guilty to assault only to avoid a trial.

"Why would I have to threaten anybody? I have the looks. I always did. I don't need to force myself on anybody for anything.

"Being honest with you, women do like cops," he said. "Women love guys in uniform."

Carre also disavows his plea, saying he did nothing more than touch the woman's leg and make a sexual remark.

Carre said he couldn't reconcile his behavior that night with his disdain for Fallon's past treatment of women. "I don't know," he said. "I just went with it."

'Power and control'

It can start with a police officer punching a woman's license plate into a police computer - not to see whether a car is stolen, but to check out her picture.

If they are not caught, or left unpunished, the abusers tend to keep going, and get worse, experts say.

In Philadelphia, an officer was convicted in 1997 of extorting sex from a teenager, saying that she could either give in or be arrested for a carjacking.

At trial, the prosecutor argued that a police officer doesn't need to use handcuffs or a gun: He could use the "moral, intellectual or psychological" power of his job to get what he wants.

"He was the detective," the girl testified. "He had all the power. I had no choice. Who was I? He had his badge."

After a Pennsylvania state trooper from a Montgomery County barracks pleaded guilty in 2000 to assaulting six women and teenagers, investigators learned that his attacks grew worse while supervisors shrugged off warnings, according to documents gathered in a lawsuit.

In a recent interview from state prison, former trooper Michael Evans says he began by making suggestive remarks and got bolder. Evans was confident that his targets wouldn't talk.

"If it's a former stripper or a prostitute, they might think no one will believe them," he said. "Most of these people don't have the highest self-esteem. That's why they become preyed upon."

For Evans, 39, a big part of the thrill was what he called "the power and control piece" - typical for officers who cross the line into sexual misconduct, experts say.

"I asked women to expose their breasts to me - expose your breasts and you're out of trouble," he said. "That was my rush."

For two years, until one teenager finally confided in a teacher, Evans assaulted women with increasing abandon. Once, he visited the hospital bedside of a pregnant woman who had attempted suicide, and groped her breasts and masturbated.

Even as his behavior grew worse, Evans said, he found ways to justify it.

"I would see women that were vulnerable where I could appear as a knight in shining armor," he said. "I'm going to help this woman who's being abused by her boyfriend, and then I'll ask for sexual favors."

A buried complaint

Several months before the attack on the dancer in Philadelphia, there was another complaint about Fallon, which was never investigated, according to interviews.

In the fall of 2002, a woman reported that Fallon, in uniform, came on to her in a Wawa parking lot.

Carre says he saw scrawled notes of the woman's allegations on the desk of a supervisor. She didn't want to make a formal complaint, Carre said.

" 'I bet you really look sexy in a teddy,' " Fallon said, then followed her home and blocked in her car, according to Carre's account of the notes he saw.

In an interview, Fallon acknowledged that the woman complained and that one of his bosses - he said he couldn't recall which one - asked him about it. But he said the truth was that "she came on to me." She wanted to pretend he was responding to a 911 call, he said, and she would answer her door in a teddy.

Fallon said he didn't know the woman's name; she could not be located for her version of events.

Her complaint was tossed out after another officer said the same woman had made sexual overtures to him, Fallon said. That officer didn't respond to a request for comment.

Philadelphia's police manual says all citizen complaints must be forwarded to Internal Affairs - even anonymous ones. Only the police commissioner may reject a report as frivolous and not worth investigating.

Capt. Mark Everitt, who ran the 15th District at the time, said in a court filing that he never heard even a rumor about any sex-related complaints against Fallon.

Whatever happened to the Wawa report, Carre insists that he warned several bosses - not Everitt - about Fallon's sexual misconduct. "He should have got transferred or fired," Carre said. "... They were supposed to take care of it. They didn't."

Once, Carre says, he and Fallon were 45 minutes late to a homicide scene because Fallon was visiting a girlfriend.

" 'He was in there banging some broad,' " Carre says he told an irate supervisor, Sgt. Patrick Lamond.

Lamond told The Inquirer: "It may have happened and I would have snapped out at the time, but I don't remember."

Fallon and Carre said it was easy for officers to chase women on the night shift because the city doesn't have enough sergeants watching.

Naish said the city tries to keep an "appropriate" number of sergeants on duty. "Are there times when there's not enough supervision? It can happen."

As for the suggestion that on-duty sex is routine on midnight patrol, Naish said: "For anyone to say that there's sex happening all the time, that is not happening."

Driving while female

Sex abuse by police has received little of the attention or urgency given police brutality or shootings.

A handful of studies suggest the magnitude of the problem. In one of the earliest, Roger L. Goldman and Steven Puro of St. Louis University examined Florida cases from the 1970s and 1980s in which officers lost their law-enforcement certifications.

To their surprise, the researchers found that sexual misconduct was the most common type of police abuse of citizens, more prevalent than thefts or beatings.

That statistic was buried in the records and had to be teased out. In some cases, they found, police demands for sex had been labeled as a form of bribery.

A 2003 analysis found that sexual misconduct was the leading reason that officers lost their badges in Utah. Of 80 officers removed over a two-year period, 25 were disciplined for sex offenses, the Salt Lake Tribune reported.

Another study - called "Driving While Female" because so many cases begin with traffic stops - argues that the problem "parallels the national problem of racial profiling."

Their research documented the failure of some victims to come forward, and the official skepticism that greets many who do.

As a result, "there is good reason to believe that these [reported] cases represent only the tip of the iceberg," said the 2002 study, by Samuel Walker and Dawn Irlbeck of the University of Nebraska.

'Like a brotherhood'

One woman who kept quiet was Dannielle Bellerjeau, a culinary school graduate from Abington who says she spent two hours trapped in the back of Fallon and Carre's patrol car hours before they attacked the dancer.

Her story came to light when Internal Affairs tracked her down by methodically contacting women the two officers had stopped. Bellerjeau says she didn't come forward earlier for fear of police retaliation.

"It's like a brotherhood," she said in an interview. "You do something wrong to one of them and they're all over you."

The night of Dec. 11, 2002, Bellerjeau encountered Fallon and Carre when they pulled over her Dodge Neon for running a red light at Levick Street and Torresdale Avenue in Mayfair. After finding marijuana in a cigarette pack, the officers handcuffed Bellerjeau and a female friend and put them in the patrol car.

Bellerjeau, then 23, said the officers offered a way out: " 'You can either get a ticket or you can go to jail or you can come hang out with us in a dark place and not get either one.' "

For about two hours, Bellerjeau said, she and her friend parried suggestions that they "party" at Magnolia Cemetery, a block away.

"I'm like, 'What good things could happen in a cemetery?' Not many," she said.

At one point, she remembers, Fallon said: " 'You need to willfully make a decision.' " That struck Bellerjeau as meaning that "if I agreed to it, it was consensual."

Finally the officers let them go. "Get the hell out of my car," one said.

The officers give different versions of that encounter. Fallon said that nothing sexual or improper took place during what he said was a routine stop.

Carre says his partner did try to lure the women to the cemetery. In his version, Carre cursed Fallon and told him to back off.

Bellerjeau said the two officers acted in concert. "Never did Carre try to stop him or try to be the good guy," she said.

Little action

Criminologist Timothy Maher, who has surveyed chiefs and rank-and-file officers about sexual abuse, said the profession recognizes the issue but has not done much about it.

"Chiefs consider it a problem, but are taking no proactive steps," said Maher, a former police officer who now teaches at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. "It's all reactive."

Maher and other experts say police supervisors need to target sexual misconduct in the same aggressive way they have tackled police shootings and racial profiling.

These problems dwindled once commanders put in place better screening of recruits, improved training, increased street supervision, and more rigorous handling of complaints.

In Philadelphia, recruits get ethics training in a class that includes some mention of sexual misconduct. There is no course devoted solely to the problem, according to the department's training curriculum.

Eugene, Ore., was forced to confront the issue after two police officers assaulted 20 women, leading to their arrests and costing the city millions in payments to victims.

Greg Veralrud, one of the victims' lawyers, said departments need to root out a backslapping, locker-room culture that can lead to supervisors laughing off women's complaints.

"There was a tolerance that had developed, a kind of boys-will-be-boys, shrug-your-shoulders attitude," he said.

City Manager Dennis M. Taylor said Eugene police now thoroughly investigate all complaints - making no judgment about "who is believable and who is not."

Before, Taylor said, "There were reports of sexual misconduct, reports of sex crimes, and they were not taken seriously. Many of the officers discounted them. This can't be done."

A final victim

Fallon and Carre's next encounter with a woman on the street would be their last in a police uniform.

It was about 3 a.m. when the partners ran into a 25-year-old woman who danced at the all-nude Daydreams club in the neighborhood.

The sole daughter in a family with four boys and a high school dropout, the woman had been stripping since she turned 19. (She has since quit.) The two officers found her at a 7-Eleven two blocks from where they had allegedly held Bellerjeau.

The dancer was nervous because she was driving without a license - she couldn't get one because of a history of seizures. She had pulled in to buy cigarettes when Fallon and Carre pulled up next to her, and demanded to know whether she was high or drunk. In fact, she had been drinking and smoking marijuana laced with PCP.

The woman said she tried to fend them off. If they had any questions, she told them, "You can ask me right here."

"No," one said, "You have to get in the back."

They pulled the car into an empty lot in the shadow of I-95 where, she said, they took turns holding her down and raping her.

"They were both yelling and screaming that I'm a whore. I'm a dirty dancer. I'm going to take care of them," she testified.

She said Carre raped her while Fallon held her down with one hand and masturbated with the other. Fallon raped her next, she said.

She did her best to fight back - "fighting, screaming, hoping someone would hear me. There wasn't no one around."

As soon as they let her go, she reported the assault. The same day, police took away the officers' guns and got a court order to seize their uniforms and underwear. Tests found semen containing Fallon's DNA. None of Carre's DNA was found.

They were arrested and fired a month later.

When Internal Affairs began combing through their paperwork, Lt. John Echols later said, he was "sort of in awe" by what he found: a string of other women who said they were abused or harassed by one or both officers.

On the eve of a trial, Fallon and Carre struck a deal with prosecutors and pleaded guilty to indecent assault and official oppression - using their police powers to commit a crime. Rape charges were dropped and they avoided jail.

In spite of their guilty pleas, both now insist that they are innocent. Again, their stories differ.

Carre says he only watched while the woman voluntarily had sex with Fallon. Fallon says that he and Carre had sex with her, but that it was her idea.

"She goes, 'Is there any way you can lose your partner?... I think you're cute,' " Fallon said.

Both men remain bitter. "The whole case is a joke," Fallon said. "I took the deal to get on with my life. For 10 minutes of pleasure, I've been suffering since 2003."

In court, the woman she said she has never shaken her memory of the attacks.

"I'd like you to know that they did rape me," she told the judge as he sentenced the officers to probation. "They took my life away from me."

Contact staff writer Nancy Phillips at 215-854-2254 or at nphillips@phillynews.com.