The 'impostor' syndrome of first-generation Penn students: Uneasy among privileged, distanced from family

Even as we speak grandly in this country of kids doing better than their parents, the emotional cost of rising is rarely acknowledged. And places like Penn are where the often unseen drama of being class-mobile plays out.

First in an occasional series that follows a group of first-generation college students through their freshman year at the elite University of Pennsylvania

On Move-In Day at the University of Pennsylvania this summer, parents unloaded cars filled with boxes, suitcases, and their most precious cargo: teenage scholars who bested 91 percent of some 40,000 applicants to enter the Class of 2021.

Penn helpers in blue "Move-In Team" T-shirts hopped to like bellmen at the Ritz, offering rolling bins and muscle to moms and dads installing their children in one of the most elite institutions in the world.

Unnoticed by the blue shirts, freshman Carmen Duran, 18, carried her own suitcases to her room.

"I was jealous of people with parents helping them move stuff," said Duran, a working-class Mexican American from tiny Maiden, N.C., whose family couldn't afford the trip. "I did it alone."

Duran, who graduated high school with a 5.09 grade-point average, is a first-generation college student – neither of her parents earned a four-year degree. She's one of around 300 first-generation students in her class of 2,457.

Kids whose parents have college diplomas know how to apply to a university, have a greater sense of belonging once they get there, and possess the means to enjoy an enriched college experience.

Students whose parents didn't matriculate often arrive at Penn's privileged 302 acres thinking of themselves as impostors — stowaways on a steamship. Most worry that their acceptance letters and financial-aid packages were cruel hoaxes soon to be reversed. Minnesota psychologist Barbara Jensen calls them "crossovers," voyagers from the working class who are advancing — with difficulty — into the sanctified territories of the middle and upper classes.

As it happens, crossing over is a relatively rare event.

A federal study released last month showed that among 2002 high school sophomores, nearly half with a parent who earned a B.A., and 60 percent with a parent who earned a master's degree, obtained a college degree or higher at least a decade later. Just 17 percent of students who had parents who didn't go to college earned B.A.s in that time frame, U.S. Department of Education figures show.

Complicating the crossover journey, many first-generation students feel guilty about using precious family resources to be at school. Although not all first-generation students are low-income, often they had to quit jobs that were helping to keep their families afloat.

And college education itself distances kids from their families, because freshman year at Penn is Rung No. 1 on the ladder of social mobility, an ascent that leaves mom and dad behind.

Uneasy among the privileged at school, and estranged from the very people who launched them, these students find themselves in "parallel universes," said Pam Edwards, director of the Penn College Achievement Program, which serves first-generation and low-income students. Ultimately, said Edwards, herself a first-generation student, "they don't fit in at home or at school."

With decent-paying blue-collar jobs evaporating, college becomes essential as a tool to battle widening income inequality. In the past, schools used race as a primary criterion to diversify their campuses and reach out to students with meager life chances. Recently, however, class has become a major factor in these calculations.

But even as we speak grandly in this country of kids doing better than their parents, the emotional cost of rising is rarely acknowledged. And places like Penn are where the often unseen drama of being class-mobile plays out.

The difficulties of being first-generation at Penn are becoming clearer for Duran.

"I love Penn, but sometimes I feel I'm at a disadvantage here," said Duran, so sought-after a student that she was offered a potential $2 million in scholarships from universities and foundations.

"I'm from low economic status in a rural area. My father's incarcerated. And Penn kids are saying the best ways to stay warm in winter are $900 Canada Goose jackets!

"But I can't talk about things like that to my mom. I already feel disloyal to her." Duran said, crying. "I feel like I'm leaving her behind. My friends, too. We're in different worlds now.

"It's already hard to tell them what's going on in my life. And how can I complain when I'm at an Ivy League school?"

‘I don’t know why I’m here’

Crossover kids feel tremendous pressure to do well.

"They are looked on by their families and communities as the ones who got out," Edwards said. "They need to represent."

Yet what they're doing – moving away from the cramped apartment, the ailing grandfather – is sometimes seen by overwhelmed working-class parents as selfish.

"The predominant middle-class culture at Georgetown and Penn teaches you to grow up to be independent of your family," said Sherry Linkon, director of the Georgetown Writing Program and a leading working-class studies scholar. "But it's working-class to take on family responsibility ahead of your own needs."

Embodying the latter notion, Penn first-generation freshman Tiffany Wong, 17, from a low-income family in Oakland, Calif., is so accustomed to helping her father, a refugee from Vietnam, and her mother, a Chinese immigrant, that, before leaving for college, she gave them half of the $2,000 she earned from a summer job so they could pay bills and "treat themselves to go out and eat."

With the stakes to excel so high, crossovers worry about measuring up.

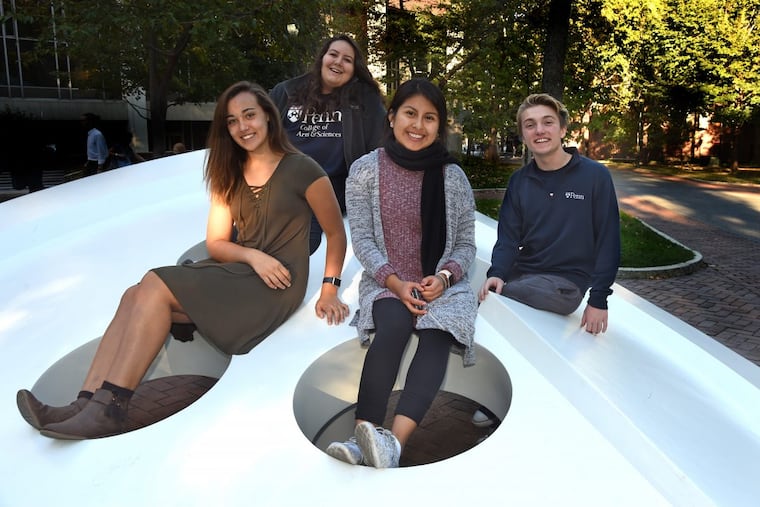

"How am I supposed to manage here with kids from better schools?" asked Daisy Angeles, 18, a first-generation freshman from Yakima, Wash., and the oldest of seven children of immigrant parents from Oaxaca, Mexico.

Angeles confessed that she feels like an impostor. "These other Penn students went to private schools, had SAT prep. All first-generation students say, 'I don't know why I'm here.' It's a struggle that goes unacknowledged."

When she shares her worries with her parents, they're loving but ineffective, exhorting her to sleep more.

"It'd be nice to have a parent who can say, 'Oh, when this happened to me in college, I did this or that to fix it,' " Angeles said.

As tough as academia can be, for now, Angeles said, her biggest worry is finding a job.

Even with generous financial aid to first-generation students defraying much of the cost of four years at Penn — nearly $300,000 — Angeles and other first-generation students still need cash.

When dining halls are closed during breaks, some first-generation students have trouble finding meals. Campus organizations such as the First Generation, Low Income Program (FGLI), and Penn First can help. Penn also has a food pantry for students.

But the stigma for utilizing such services on a rich campus can be damaging.

‘Don’t think you’re smarter’

Things are not dire for first-generation Penn student Haley Carbajal, 18, from Belle Fourche, S.D. But some extra cash would help, so she sat outside the David Rittenhouse Laboratory one morning searching the web for a babysitting job. "I'm used to work," said Carbajal, who started her own iced-coffee vending business when she was 15.

Before classes began, Carbajal's parents sat with her at a Starbucks, fretting.

"My biggest worry is she'll never come home," said Carbajal's father, Anthony, 43, who makes digital maps. "Things are changing permanently."

Carbajal's mother, Trista, 42, who works for an insurance company, recalled her daughter's old job at a Subway shop. "She said she was going to work there forever. That was OK with me," Trista said, tearing up.

Already morphing from Republican to Democrat, Carbajal explained: "The East Coast opens your mind, and South Dakota is very conservative. Now, my parents and I don't discuss politics anymore. And my old friends – I'm changing at a faster pace than they are."

Like older first-gen sisters with wisdom to impart, Penn juniors Candy Alfaro, 19, from Soledad, Calif., and Anea Moore, 20, from Southwest Philadelphia, know the perils and perks of mobility – and how education alters family dynamics, from minor disagreements to bridge-burnings.

Alfaro, the daughter of Mexican-born farmworkers, said her mother complains that college is turning her into someone new. Crying, Alfaro said: "My folks started to tell me, 'Don't think you're better or smarter than us.' "

Sitting beside Alfaro in the FGLI office, Moore, who is African American, began crying in empathy.

Moore's parents both worked in nonacademic jobs at Penn, where they met. "My mother was afraid of Penn, and felt like she didn't belong" as a working-class African American, Moore said. "It was heartbreaking."

But when Moore got accepted, her father exclaimed, "My daughter belongs!" Still, the two would clash in "terrible" arguments when it became clear Moore preferred to think more like her teachers than her dad, and to spend time away from the family to study. "You want to go to college and make your parents proud," Moore said, tears streaming down her face, "but all the while you're distancing yourself from them. I started assimilating to the middle class early."

While she was still acclimating to Penn, Moore suffered overwhelming tragedy: Her father died of lung disease, and her mother died of a heart attack not long after. Sorrowful but ambitious, Moore's class battles continue — with an aunt who accuses her of acting "better than everybody," and with her sister in Southwest Philly, who dismisses Moore for "sitting with these white kids on that campus and not coming home."

No such dramas have befallen Anthony Scarpone-Lambert, 18, of Chalfont, whose unconventional first-gen life includes having been on Broadway in The Miracle Worker and Mary Poppins when he was younger.

A video of his exuberant reaction to getting accepted at Penn went viral, making him a minor campus celebrity. Despite that, Scarpone-Lambert shares a crossover's lament: "Sometimes, I feel everyone here is better than me."

But he inspires admiration among students whose parents have degrees, like new study partner Lucy Stinn, 19, the daughter of a Texas oil executive: "First-gen students meet people here who always got everything they wanted," she said. "But I think they have a better work ethic and better sense of self. And they're more humble."

Still, as of early October, many first-generation students continue to feel like outsiders. And, Duran said, when she tries to impart her story of being the first in her family to attend college, "some people here can't relate to it. They're almost bewildered."

Neither can her mother grasp the nuances of her new, middle-class days.

It all leaves Duran with a sense that she has a lot to learn in her still-developing life:

"I have to worry about a lot of things the other students here don't. I was always an underdog," she said. "But I'll never let any of the hard stuff stop me."