Singer and actress Lena Horne dies at 92

Over her dazzling five-decade career, Lena Horne soared from Cotton Club showgirl to the screen's "bronze bombshell" to one of Broadway's grandest dames. She made her remarkable flight while toting the expectations of two races on a thrush's fragile wings.

A shorter version of this obituary appeared in the final edition of Monday's Inquirer.

Over her dazzling five-decade career, Lena Horne soared from Cotton Club showgirl to the screen's "bronze bombshell" to one of Broadway's grandest dames. She made her remarkable flight while toting the expectations of two races on a thrush's fragile wings.

The 92-year-old actress, activist, and vocalist, honored with Grammys, a Tony, and the NAACP's highest award, died Sunday night at New York-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City. The cause of death was not disclosed.

In 1943, when she made her name in the Hollywood musicals Cabin in the Sky and Stormy Weather, Miss Horne became the first African American movie star. Studio moguls worried that the 26-year-old singer might be too exotic for the white public. By 1963, black-pride leaders thought her too assimilationist.

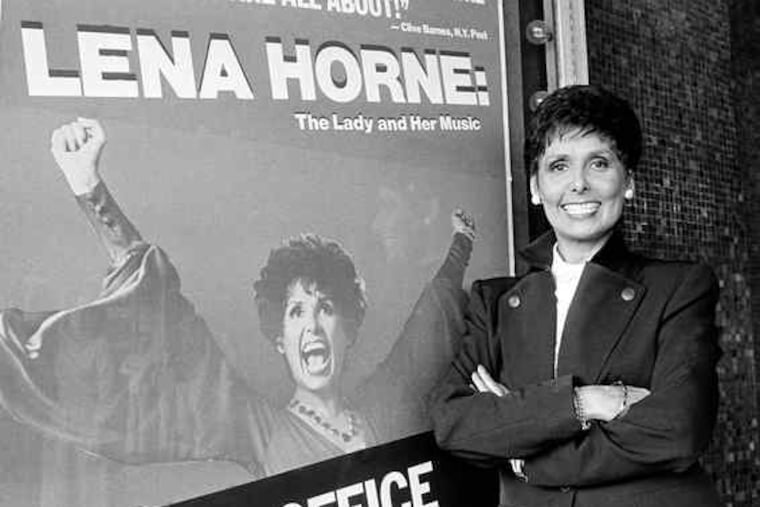

It is a measure of the glacially self-contained performer that she prevailed despite stormy weather from both sides. She used her experience in Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music, a 1981 one-woman Broadway show, to sing the history of the civil rights movement, over two hours thawing from iceberg to roaring river. She won a Tony Award for a triumph that was both social statement and coup de théâtre.

Lena Calhoun Horne was born June 30, 1917, in Brooklyn, N.Y. One of nature's flawless creations, she embodied the contradictions and confluences of race in the United States. Among her forebears were both slaves and a vocal proponent of slavery, Vice President John C. Calhoun. The black descendants of Calhoun traced their ancestry to Senegal; the Hornes were descended from British adventurers, American Indians, and freed slaves.

Miss Horne's paternal grandparents, Edwin and Cora, bought a brownstone in Brooklyn in the 1890s. Edwin was a teacher and political lobbyist, Cora a suffragist and founding member of the NAACP.

The entertainer's parents, Teddy and Edna, split when she was 3, leaving her with grandmother Cora. Cora Horne imbued her granddaughter with high ideals and debutante manners. Lena attended the private Ethical Culture School and later studied at Brooklyn's Girls High. Cora, a college graduate, expected her charge to become a teacher, but Lena's mother, an aspiring actress, balked.

By age 10, Lena was a shuttlecock being swatted between her grandmother's proper home and her mother's increasingly squalid arrangements. Frequently when on the road, Edna farmed out her daughter to acquaintances. For many years, Lena's father was out of the picture. Looking back in 1974, the entertainer observed that it seemed every time she became close to a caregiver, she was snatched away.

When Lena was 16, Cora died of an asthma attack, and Edna won the battle of wills by default. Miss Horne quit Girls High and began her show-business apprenticeship at the Anna Jones Dance School.

Edna "had the unrealistic idea that she could become a star on the stage, a generation before any Negro woman could do that," Miss Horne wrote in her 1965 memoir, Lena. With her own ambitions snuffed, Edna shoved her daughter into the limelight.

Miss Horne was only 16 when she joined the chorus of the Cotton Club, the legendary Harlem nightspot nicknamed "the plantation" for its black performers and audience of white swells. Wearing a costume that consisted of a smile and three strategically placed feathers, she helped provide decor for headliners such as Cab Calloway.

Eager to break from a punishing routine of three shows a night, the chorus girl auditioned as a vocalist for the bandleader Noble Sissle in Philadelphia. He hired Miss Horne, rechristened her Helena, and bought her a chic dress at John Wanamaker. Thus the Cotton Club runaway came to tour the country with one of the black bourgeoisie's favorite bands.

On the road, she reconnected with her father, a Pittsburgh civil servant and numbers runner, who introduced her to Louis Jones, a preacher's son. They married in 1937, and the following year, Miss Horne gave birth to a daughter, Gail. The couple's son, Edwin, known as Teddy, was born in 1940.

To supplement the family income, Miss Horne made her screen debut in the 1938 Duke Ellington film The Duke Is Tops, also known as The Bronze Venus. She returned to Broadway - where she first appeared in the 1934 musical Dance With Your Gods - in the short-lived revue Blackbirds of 1939.

When her marriage dissolved in 1944, mother and father fought for child custody. Jones won Teddy; Miss Horne got Gail.

It was while job-hunting in New York that Miss Horne first heard what was to be a career-long refrain: She wasn't anyone's idea of a "black" entertainer. She wasn't dark-skinned. She didn't sing the blues. And she didn't swing, though she learned to. An impresario at the Latin Casino, then in Philadelphia, advised her to pass for Latina.

Then bandleader Charlie Barnet hired her as a vocalist in 1940, making her one of the first black performers to sing with a white band. While she ran the gauntlet of racist hotel clerks and bookers, Barnet treated Miss Horne with care, writing special arrangements for songs, such as "Good-for-Nothing Joe," that accentuated her ability to playfully tease the lyrics. From the beginning, she could cut to the heart of a song. Over time, she would learn to deliver its soul.

Because she wanted a stable home life for her daughter, Miss Horne quit Barnet after six months. She was hired by Barney Josephson at his Greenwich Village nightspot, Cafe Society. There she met the singer-actor Paul Robeson, a former protégé of her grandmother's, who cultivated her emerging racial pride. She also enjoyed a romance with the prizefighter Joe Louis.

Of the many men in her life, said Miss Horne, only one was her "soul mate": Billy Strayhorn. A composer-arranger for Ellington, Strayhorn was openly gay - and was the courtly Galahad figure about whom she had always dreamed. For decades after his death in 1967, she kept his photo by her bedside.

In 1941, when Miss Horne got a job offer in Los Angeles, the NAACP head, Walter White, encouraged her to accept, hoping her cabaret appearances would lead to movie work and open Hollywood to other black performers.

Within months, she was offered a contract at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. To avoid being typecast as a domestic or a jungle princess - the usual roles for women of color - Miss Horne asked her father to negotiate terms. He deadpanned, "I'm going to get you a maid, because that's the role you'll be playing." To mogul Louis B. Mayer, he insisted, "My daughter has a maid, why should she play one on screen?" Her deal stipulated that she "would not have to do illiterate comedy or portray a cook."

The strategy worked - to a point.

"They didn't make me a maid," Miss Horne recalled in her memoirs. "But they didn't make me anything else, either." After playing a torch singer in Stormy Weather and a temptress in Cabin in the Sky, she was limited to musical interludes in movies such as I Dood It (1943), Two Girls and a Sailor (1944), and Ziegfeld Follies (1946). These solos, which often featured Miss Horne in elegant repose, could be cut when the movies played the South. Miss Horne was, she memorably wrote, "a butterfly pinned to a column, singing songs in Movieland."

During the war, she entertained troops for the USO. In Arkansas, she was scheduled to give two performances, one for white GIs, the other for black soldiers. When she inquired about the sea of white faces at the "black" show, she learned they belonged to German POWs, who, according to the Southern custom of whites-first, were given preferential seating. She refused to perform and filed a complaint with the NAACP, only to be censured by the USO for declining to sing.

Back in Hollywood, she was caught between the expectations of the NAACP and the confused racial attitudes of show business, where she was widely regarded as too light-skinned for the black roles and too black for mixed-race roles. To Miss Horne's horror, Jeanne Crain, who was Caucasian, was cast as the octoroon who "passes" in Pinky (1947). And Ava Gardner, Miss Horne's good friend, was cast as the mixed-race Julie in Show Boat (1951), a role Horne hoped to get. For their part, though, studio brass thought that an obviously black actress was wrong for roles in which the disclosure of the character's mixed race was a major plot point.

The director Billy Wilder, an admirer, hoped she would star in his updated Camille. He envisioned her as a Harlem courtesan beloved by naval officer Tyrone Power, whose father, unbeknownst to him, is black. It never came to fruition.

The happiest thing to come of Miss Horne's Hollywood experience was her 24-year marriage to MGM conductor and arranger Lennie Hayton, who was white. Because interracial marriage was illegal in 30 of the 48 states, they wed secretly in Paris in 1947, and did not make public their troth until 1950. Miss Horne credited Hayton with widening her vocal range and taste.

As a result of her friendship with Robeson, a communist sympathizer, and her support of antifascist causes, Miss Horne was blacklisted in 1950. That this luxury-loving actress could be a communist struck her intimates as improbable. Her friend Ludwig Bemelmans, creator of Madeline, observed that the impeccably coiffed and coutured performer made her entrances as though she were the former queen of a Balkan country.

Still, to obtain work in nightclubs and on television, Miss Horne was pressured to denounce communism. In a prepared statement that must have caused her extreme pain, she said, "Paul Robeson doesn't speak for the American Negro" - which mollified the rabidly anti-communist gatekeepers of show business.

During the '50s, Miss Horne and her husband were gypsies, working in clubs from Las Vegas to Paris. After she was cleared of communist ties, Miss Horne signed a contract with RCA and made Lena Horne at the Waldorf-Astoria, which broke the label's record for biggest-selling album by a female.

After a Broadway hiatus of almost 20 years, she returned to New York theater in the 1957 musical Jamaica. No one much liked the production, but everyone loved her. It ran 18 months.

Though she was a card-carrying NAACP member from age 2 (Cora had taken care of that), Miss Horne was at first reluctant to join the civil rights movement. "How can I stand there in a $1,000 dress and sing 'Let My People Go?' " she asked a journalist.

But after four black children died in the 1963 bombing of a Birmingham, Ala., church, Miss Horne called the NAACP to ask what she could do. She sang at rallies in Jackson, Miss., where she befriended Medgar Evers, who was assassinated shortly afterward. Her old classmate Betty Comden wrote anti-bigotry lyrics to the Jewish song "Hava Nagila," and Miss Horne sang the work, titled "Now," at a Carnegie Hall benefit for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in 1963. It became her first hit, and she became the embodiment of radical chic.

Her activism caused friction in her marriage, and for most of the 1960s she and Hayton lived on opposite coasts. Although she attended the 1968 funeral of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. alone, she reconciled with her husband shortly afterward. The following year, she starred as a madam opposite Richard Widmark in Death of a Gunfighter. It was her first nonstereotyped film role.

In the 12 months that began in April 1970, Miss Horne buried her father; her son, who died of kidney failure; and Hayton, who suffered a heart attack. Her grief was immobilizing. She emerged slowly from her emotional paralysis, first touring with Tony Bennett, then appearing as Glinda the Good Witch in the 1978 movie The Wiz (directed by her son-in-law Sidney Lumet), finally appearing in a Los Angeles stage revival of the musical Pal Joey. When it failed, she did what was to be a farewell tour, but enjoyed herself so much she got the idea for a one-woman show.

The Lady and Her Music ran for 333 performances, setting a Broadway record at the time for a one-woman production. For the first time in her life, Miss Horne was able to revel in her contradictions: There she was, elegant in a flowing Greek-goddess gown, performing a field-hand shuffle.

The pinnacle of Miss Horne's public life may have been in 1983. That year she received the Spingarn Medal, the NAACP's highest honor, from the group cofounded by her grandmother. It was followed in 1984 by the Kennedy Center's lifetime achievement award.

At the Kennedy Center ceremony, Hollywood's first black star was heartily embraced by Lillian Gish, the lead of the race-baiting 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, a movie Miss Horne had vociferously protested. For some, their hug signified a national reconciliation between black and white America. For others, it was just two showbiz vets paying mutual tribute. Either way, it was a testament to the cultural change wrought by Miss Horne during over five decades in the public eye.

Miss Horne's survivors include her daughter, Gail Lumet Buckley, and six grandchildren.