Ali made us think he would never die

He is hunched over a bowl of soup in a Las Vegas diner, and each spoonful is delivered hesitatingly, with slight tremors, the price of pugilistica dementia, the price of all those brain-pan-rattling punches in all those fist fights, the price of giving the people what they have paid for: Entertain us, Muhammad. Give us a show.

He is hunched over a bowl of soup in a Las Vegas diner, and each spoonful is delivered hesitatingly, with slight tremors, the price of pugilistica dementia, the price of all those brain-pan-rattling punches in all those fist fights, the price of giving the people what they have paid for: Entertain us, Muhammad. Give us a show.

And at the heart of it, that's what Muhammad Ali, who died Friday at the age of 74, was. A fighter, of course. A boxer, to be sure. But a showman, in the ring and even more so out of it. He was, in many ways, the most remarkable man of the last century. The pope asked for his autograph. Ferdinand Marcos looked at the assemblage of the millions in Manila gathered for his epic duel with Joe Frazier, and told him: "Good thing you're not a Filipino or I'd have to shoot you."

There never was a completely satisfactory explanation of what it was that drove the people to him, like little steel magnets.

He inflamed much of the populace with his stand against the Vietnam War, but over the years that flame waned, and his popularity ascended. He became the Pied Piper. He loved to take a seat in a public place, unannounced, and sit and wait. For what? For the crowd, and it formed in twos and threes.

And they smiled.

And they giggled, here in the audience of a man who once claimed to be the most recognizable face on the planet. There was an innocent, childlike manner about him. For a long time, before the disease locked his fingers in rigidity, he delighted in performing magic tricks.

And how appropriate that was, because that's what he was, wasn't it? A magician. Made you see what wasn't really there. Or was there?

In the early days, much of the magic was in the ring, where he was so adroit at escaping that he made you believe that he was impossible to hit. That, we would learn later, turned out to be cruel deception.

Dancing between raindrops we called it, and he was elegant and flowing, such a glorious sight, so mesmerizing, that the ballet genius George Balanchine once was moved to speak in awe: "His legs . . . he fights with his legs."

But that magic is no more. The magician walks in a shuffling, unsteady gait, and those legs, that once propelled him around the ring, round and round and round, until you swore he was dancing on the ceiling, ah, those legs, they are gone, taken by that merciless disease and by the battering.

Was there, way back, a pact of some sort reached, and where was bestowed on him magical powers, some sort of bargain arrangement that offered oh so tempting things almost supernatural but carried a terrible counterbalance?

For starters, those fists swift and surgical. Was the counterbalance hands that struggled to navigate a spoonful of soup into his mouth? And that voice, so quick with quip and wit, became a slurring, rasping whisper. And those legs, the ones the ballet maestro swooned over, they betrayed him, enfolded him in an unyielding paralysis.

He faded in and out, in a vacant gaze, and when he forgot his medicine or skipped his nap, he had what they used to call on a rice paddy patrol in Vietnam the Thousand Yard Stare. And yet for all of this, despite this daunting medical directory, he slogged on. Can anyone equal such staying power? He refused to leave, to succumb, to yield.

Hunched over that Vegas soup, he smacks his lips and nods in approval.

I leaned in so he could see me smile as I ask: "Didn't they have you dead by now?"

"Fooled them," he said.

Yes, yes you did. Fooled us all. It's been years and years since that conversation I had with him. So I repeat: Can anyone match such a ferocious refusal? There was the inevitable, of course, but he had us wondering whether he was going to be the exception.

And in my mind's eye I see him once again looking down the counter. He has had his eye on a slab of cherry pie all along.

One night at his Deer Lake training camp I watched him make a midnight raid on the kitchen. He had a notorious sweet tooth, and training for the next fight was always a struggle.

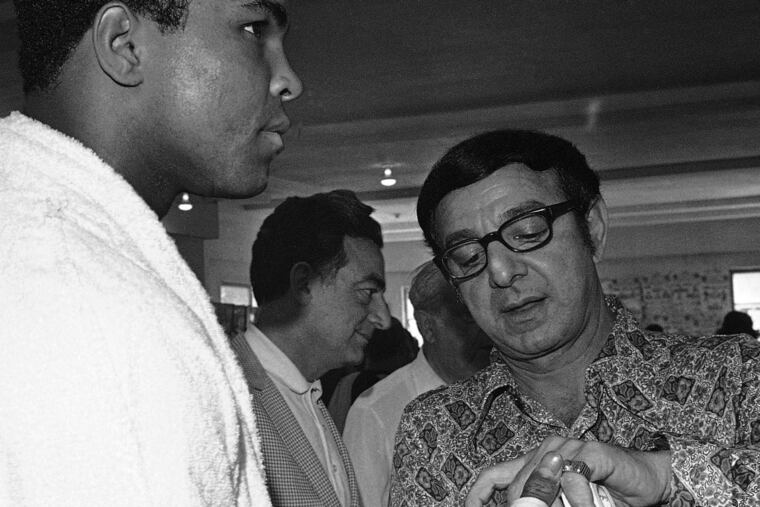

So we sat there, the three of us - Ali; Angelo Dundee, the legendary trainer; and me. Ali ate a cherry pie. The whole thing.

"Run an extra mile tomorrow," he promised.

Angelo rolled his eyes and asked: "How would you like to have his dreams tonight?"

My very favorite Ali story: Preparing for a flight, Angelo and Ali are seatmates. The attendant comes by and orders, "Please buckle your seat belt, Mr. Ali."

Ali, grinning: "Superman don't need no seat belt."

Attendant, sweetly: "Superman don't need no plane, either."

Bill Lyon is a retired Inquirer sports columnist. lyon1964@comcast.net