This election, sponsored by...

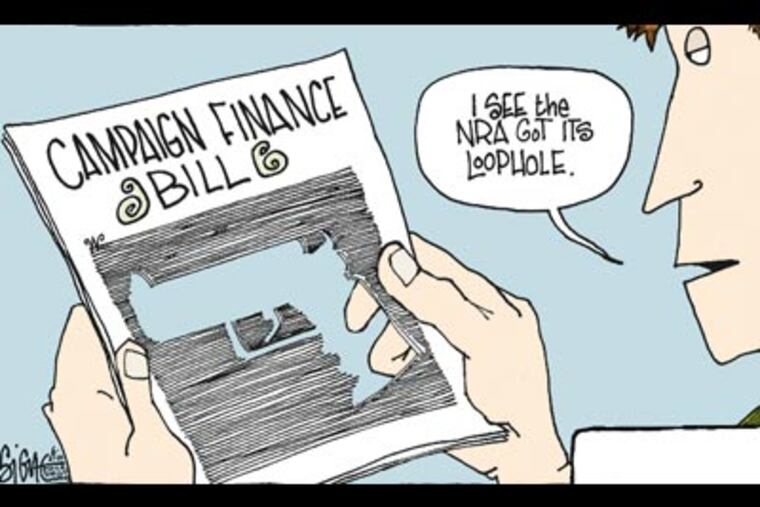

THE CAMPAIGN-FINANCE bill designed to blunt the power of special interests on the electoral process is in danger of becoming a prime example of the power of special interests on the electoral process.

THE CAMPAIGN-FINANCE bill designed to blunt the power of special interests on the electoral process is in danger of becoming a prime example of the power of special interests on the electoral process.

The story so far: In January, the U.S. Supreme Court, in the 5-4 Citizens United decision, lifted a ban against corporations and unions running independent ads in election campaigns. Many experts agreed with President Obama that the ruling would "open the floodgates for special interests . . . to spend without limit in our elections."

April: Democrats in Congress fashioned a bill that would force corporations or unions paying for ads to disclose their identities so that voters could judge if the sources were credible. They dreamed up an awkward acronym for it - the Democracy Is Strengthened by Casting Light on Spending in Elections (DISCLOSE) Act - and introduced it to well-funded and intense opposition from, you guessed it, special interests.

May: The National Rifle Association warned members of Congress that it would oppose supporters of the bill, terrifying some members of U.S. House of Representatives. Ironically, the NRA has no apparent motive for secrecy: In fact, its name on voter scorecards is precisely what causes representatives to tremble.

Last week: Democrats "carved out" an exemption from the law. At first, the exemption applied to organizations with more than a million members. When that exempted only the NRA, the threshold was lowered to 500,000 members, which included the Sierra Club, the Humane Society and AARP. Now the Congressional Black Caucus (rightly) protested - so much so that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi withdrew it temporarily.

This week: The White House officially endorsed the DISCLOSE Act, even with the NRA exemption. Members of the House are faced with the unpleasant choice of - once again - swallowing noxious compromises or killing critically important legislation, perhaps permanently.

If the financial reform law is blocked, its opponents will have more reason and resources to knock out the very members of Congress who might possibly pass it later. If the fear of special interests is high now, think what if campaign reformers are trounced in November.

We are so tired of being told a flawed deal is better than none, but this may be a case in which the warning is justified. I