DN Editorial: A decade of change has benefited the parks

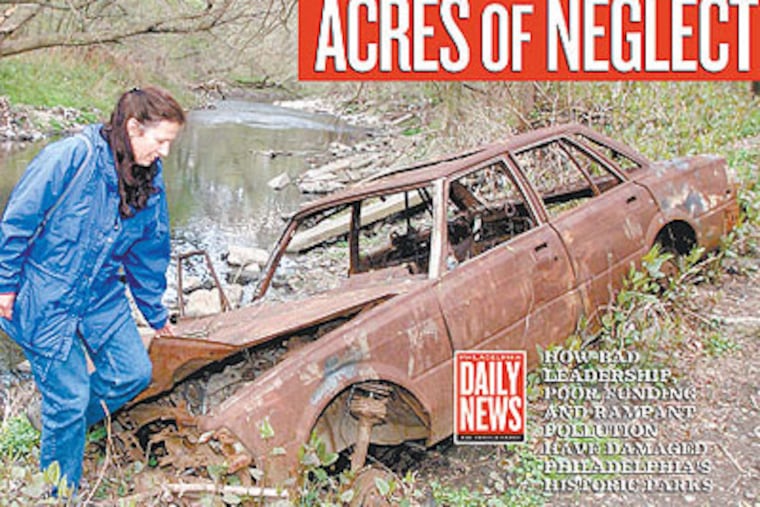

A FEW MORE ACRES, a lot less neglect. Ten years after this newspaper's editorial series "Acres of Neglect" began a multiyear focus on the poor conditions, bizarre governance structure and unrealized potential of the city's parks, we are pleased to report significant change - in fact, a transformation.

A FEW MORE ACRES, a lot less neglect.

Ten years after this newspaper's editorial series "Acres of Neglect" began a multiyear focus on the poor conditions, bizarre governance structure and unrealized potential of the city's parks, we are pleased to report significant change - in fact, a transformation.

In 2011, Philadelphia parks - at 10,500 acres, one of the largest urban park systems in the world - no longer are the dumping ground we found in 2001, when they were littered with thousands of old tires and hundreds of abandoned cars and assorted appliances, not to mention building materials and hazardous waste.

From parks that lacked basic amenities like open restrooms - but didn't lack excuses for the situation - the city's parks now offer substantial relief for visitors. In the past 10 years, the parks have added at least 31 new and improved attractions, including several cafes and museums.

In 2001, Philadelphia was isolated from a then-nascent national movement to recognize the importance of public space in the lives of cities. In 2011, it has become a leader in that movement.

And here's the kicker: the transformation has been accomplished with fewer staff and less taxpayer money.

But planting and nurturing the political will to transform the parks took many springs to blossom. Only recently has it begun to bear fruit.

The political will certainly was dormant in 2001, when Fairmount Park was in the midst of a long slide marked by decreased staffing, a flat budget from the city, and a crippling sense of victimization. The parks lacked clout in part because of a dysfunctional governance structure that had parks and recreation administered by two agencies with overlapping responsibilities: the Department of Recreation that answered directly to the mayor and the Fairmount Park Commission, a supposedly independent commission created just after the Civil War.

The Recreation Department administered some parks and the Fairmount Park Commission ran some recreation centers and swimming pools. This resulted in a wasteful duplication of services, a lack of clear accountability for policy decisions, and a learned helplessness to do anything about it.

And, like nearly everything else in Philadelphia, discussions of the parks frequently carried a subtext of race and class divisions.

The 10-year journey to the parks' transformation has followed a long and winding trail. Although the structural fixes might have been simple, real change was far more complicated - revolutionary, in fact. It required a break with tradition, a change of political alignments, and a revamping of old-but-comfortable ways of doing business.

Over the years, those who resisted moving the Fairmount Park system from an allegedly independent entity to a city department played on fearful scenarios that occasionally bordered on demagoguery: visions of the city selling off land to the highest bidders and subject to the whims of "the politicians."

Not only have those predictions not come to pass, but City Council recently voted into law a set of criteria to be followed in considering any changes in the use of public land, a much stronger protection for public lands than the old Fairmount Park Commission ever could provide.

The proof is in the looking: We did a brief spot check of the system last week, revisiting some of the more troubled spots in our original series:

In 2001, Tacony Park was a veritable graveyard for burned-out, rusted and abandoned cars. Today, a wild meadow bars access to the creek, and the creek is car-free.

Throughout the system - from East and West parks to Pennypack in the far Northeast and Cobbs Creek (also a horror in 2001) - we saw lush green and little trash. (For that, the public also deserves some credit.)A heartening sight: a park visitor walking to a trash can and depositing litter.

Bottom line: For the most part, the parks have become the inviting green public spaces they were meant to be.

Tomorrow & Friday: The Cobbs Creek Park success story. Plus: How the system really changed and what else is in store, plus Parks & Rec by the numbers.