Wrong choice for child’s home

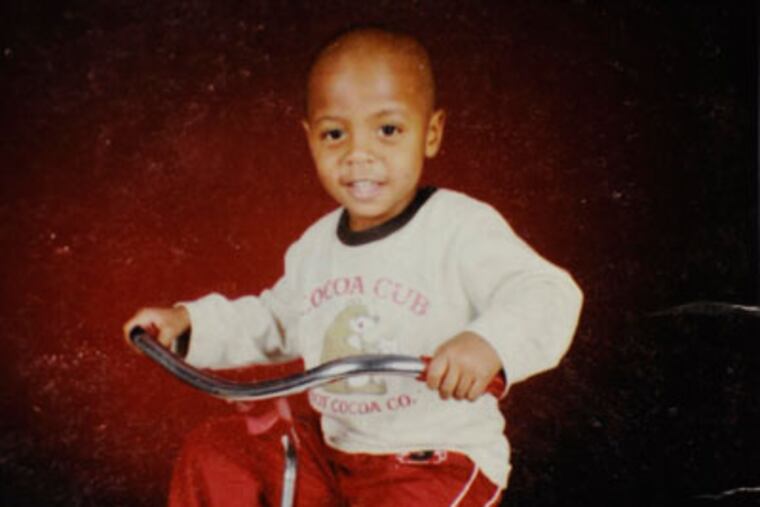

The reporting of additional information concerning the allegedchild-abuse death of a 6-year-old boy again raises questions about the protection of children in Philadelphia. Records indicate that although Khalil Wimes was not officially under the supervision of the city Department of Human Services when his death occurred on March 19, a DHS social worker did see Khalil several times when she monitored two older siblings during their supervised visits with the boy.

The reporting of additional information concerning the alleged child-abuse death of a 6-year-old boy again raises questions about the protection of children in Philadelphia.

Records indicate that although Khalil Wimes was not officially under the supervision of the city Department of Human Services when his death occurred on March 19, a DHS social worker did see Khalil several times when she monitored two older siblings during their supervised visits with the boy.

If the social worker saw signs of abuse, which others now say were clearly visible, why weren't steps taken so DHS could intercede? Is the social worker, who has been put on desk duty, solely at fault? Is her supervisor to blame? Or is it the procedures or culture within DHS?

Mayor Nutter, who promises a thorough investigation, appropriately noted that DHS workers do the best they can amid the most challenging circumstances. "They are committed and they live their work 24/7," said Nutter.

But that commitment didn't stop the death of little Khalil, who in hindsight probably shouldn't have been returned to the care of parents who had a history of neglect, if not abuse.

That a Family Court judge ordered Khalil removed from the home of loving foster parents shows what can happen when reason falls victim to an understandable preference to reunite broken families.

Khalil's reunion led to tragedy. Charged with murder are his parents, Tina Cuffie and Floyd Wimes. Cuffie has told authorities she hit Khalil in the bathroom of their South Philadelphia apartment and he fell unconscious to the floor.

The couple waited 13 hours before taking the lifeless boy to the hospital. No doubt they feared what the medical staff would say about the scars and bruises that covered almost every inch of his body. Their fears came true when the hospital called the police.

There was so much promise for Khalil after his birth, when a distant cousin of Wimes, Alicia Nixon, agreed to take the baby because his parents were struggling financially and couldn't provide a proper home. DHS had already removed Khalil's five older siblings from his parents, who had a history of substance abuse.

Khalil thrived while living with his doting foster parents. But in 2008, Wimes and Cuffie petitioned Family Court to get the boy back, and did so after meeting DHS's stipulations that they do six months of drug treatment, find an apartment, become employed, and take a parenting class.

It didn't matter that Khalil was perfectly acclimated in the home he had lived in since birth. It didn't matter that the case's social worker and Khalil's court-appointed child advocate argued against moving him.

DHS monitored the boy for a year. Two adult sisters say the abuse started once the monitoring stopped. They said the boy was beaten with fists, extension cords, shoes, books, and belts. But they never reported it. Sometimes Khalil was sent to bed without dinner. He weighed just 29 pounds at death. It's not known why a doctor said to have given the child a checkup last year didn't report signs of abuse.

DHS Commissioner Anne Marie Ambrose has made important changes since 14-year-old Danieal Kelly died of child abuse in 2006, two years before Ambrose came aboard. But little Khalil's death is glaring evidence that more changes may be necessary — not just within DHS, but also the courts, in deciding the best home for a child.