Inquirer Editorial: Time can't heal sexual abuse by priests

They knew and they let it happen! To kids! That's a quote from the movie Spotlight attributed to real-life reporter Mike Rezendes when he was investigating Boston priests accused of sexually molesting altar boys and other children 15 years ago.

They knew and they let it happen! To kids!

That's a quote from the movie Spotlight attributed to real-life reporter Mike Rezendes when he was investigating Boston priests accused of sexually molesting altar boys and other children 15 years ago.

The comment could just as well be applied to Pennsylvania authorities who for decades did precious little to stop similar abuse by priests and cover-ups by religious leaders in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Altoona-Johnstown.

A grand jury report released last week by Attorney General Kathleen Kane said an investigation had revealed evidence of "several instances in which law enforcement officers and prosecutors failed to pursue allegations of child sexual abuse occurring within the Diocese."

Cambria County Judge Patrick T. Kiniry, a former district attorney, reportedly told state investigators that the close relationship between local authorities and diocesan officials when the alleged abuse cases occurred was a reflection of the Catholic Church's influence.

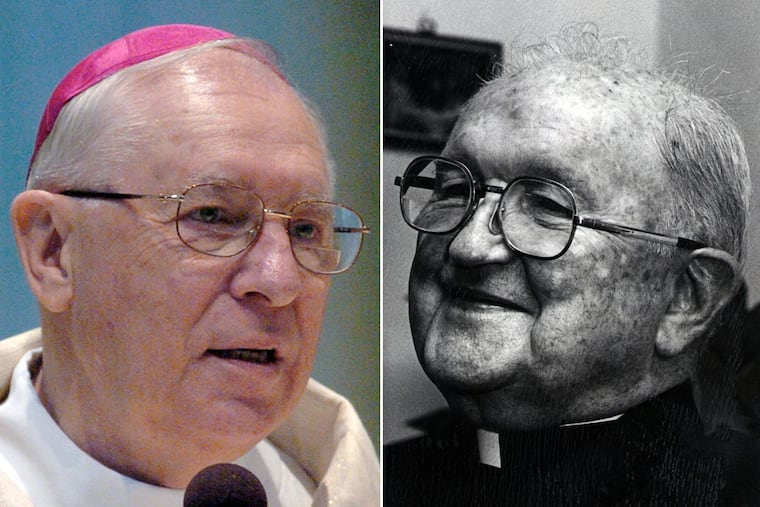

Evidence presented to the grand jury included material gathered in a raid of diocesan offices last August by state agents. They found a "secret archive" of documents, including handwritten notes sent to Bishop Joseph Adamec by the late Bishop James Hogan, which detailed alleged abuse cases, including victims' statements.

In one case, the grand jury said Hogan interceded on behalf of Joseph Gaborek, who in the early 1980s was accused of sexually violating a 16-year-old boy he recruited to work with him at two parishes. Gaborek went on a sabbatical, but later was allowed to return to work as a priest without ever being charged.

That same pattern was evident in the 2011 Philadelphia grand jury report that led to William Lynn's becoming, at that time, the highest ranking U.S. Catholic Church official convicted in a child sex abuse case. A new trial was recently ordered for Lynn, who argued that he was made a scapegoat by prosecutors trying to show how the Philadelphia Archdiocese protected priests accused of abuse.

A study commissioned by the Catholic Church said more than 4,000 U.S. priests had been accused of sexually abusing at least 10,000 children, most of them boys, in the last 50 years. The church has spent more than $2 billion to settle cases, pay for victims' therapy, lawyers' fees, and other costs.

Prosecution is unlikely for anyone accused in the new grand jury report. Statutes of limitation have expired. Some of the accused are dead. One victim committed suicide and others are reluctant to testify. The grand jury recommended lifting the statute of limitations for sexual offenses against children and suspending the statute of limitations to file sexual abuse civil suits. Those are good steps. Some crimes are too heinous to ever avoid prosecution, or deny victims restitution.