Commentary: Pa. has more to do on school funding fairness

Pennsylvania needs to take a crash course in school funding fairness. That's one conclusion drawn from the 2016 National Report Card (NRC), which gave the Keystone State a D for its inequitable funding system.

Pennsylvania needs to take a crash course in school funding fairness. That's one conclusion drawn from the 2016 National Report Card (NRC), which gave the Keystone State a D for its inequitable funding system.

Although ranked among states that generally provide high fiscal support to their school districts, Pennsylvania is in the unenviable company of 13 other states deemed regressive in their school-funding levels. According to 2013 data, the most recent available, Pennsylvania school districts with 30 percent of their student body living at the poverty level received 7 percent less per-pupil state funding than school districts with no students living in poverty. Regressive states like Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Nevada "urgently need to overhaul their finance systems to give students a meaningful opportunity to succeed in school," said David Sciarra, a co-author of the NRC.

The NRC, now in its fifth year, is the product of a study by Bruce Baker, a professor at Rutgers' Graduate School of Education and the Education Law Center (ELC), a nonprofit that advocates for public school student rights. Sciarra is ELC's executive director.

In 2014, funding inequities led a group of school districts, parents, and advocacy associations to file a lawsuit against Pennsylvania's education officials, legislative leaders, and the governor. The lawsuit accused the respondents of violating the state constitution and "for establishing an irrational and inequitable school financing arrangement that drastically underfunds school districts across the commonwealth and discriminates against children on the basis of the taxable property and household incomes in their districts."

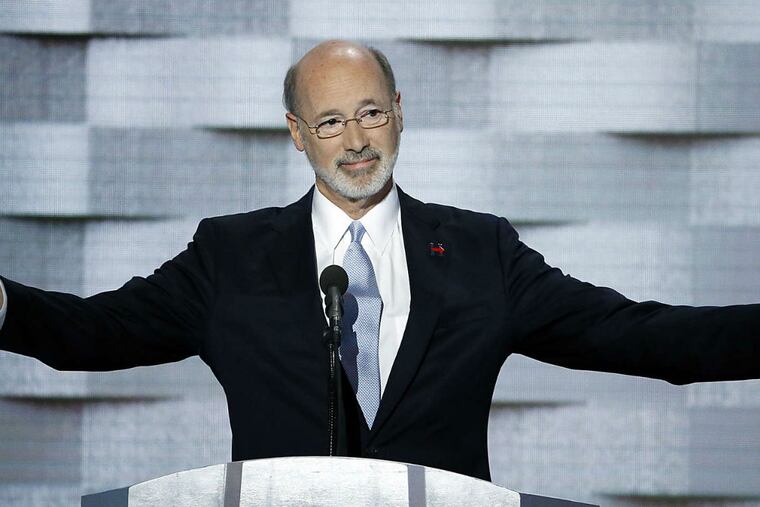

Pennsylvania, unlike most other states, has not used a systematic formula that weighs a district's operating conditions (for example, fiscal, demographic, socio-economic, and geographic conditions) since 1991, with the exception of 2008 to 2010, when Ed Rendell was governor. But a new law, signed by Gov.Wolf in June, enforces formula-based distribution of state education money in hopes of correcting funding inequities.

This new formula provides extra support to districts facing challenging conditions such as high enrollment, students living in poverty or learning English as a second language, low median household income, and weak capacity to raise taxes. But the formula only applies to a small portion of the state's education budget, causing some to wonder what impact, if any, the formula will have on school districts.

For 2016-2017, the formula distributes just $200 million out of a $5.9 billion state education budget - about 3.4 percent. School districts, though, need about $400 million more to cover mandated expenses (pensions, health care, special education, and charter school payments), according to the 2016 Report on School Districts Budgets by the Pennsylvania Association of School Administrators and Pennsylvania Association of School Business Officials. As a result, half of the school districts mentioned in this report will offer fewer educational programs. Almost half of the districts (46 percent) will also reduce staff expenses, while others expect larger class sizes, local tax hikes, borrowing, and payment delays to third parties.

The report notes that some school districts will use savings in their "unassigned fund balance" to continue service without disrupting educational programs. The unassigned fund balance is a leading indicator of a district's financial health. It is used to cover unforeseen expenses or emergencies and alleviate budgetary fluctuations caused by cash flow variations. The Government Finance Officers Association recommends that governments, regardless of size, maintain a minimum unassigned fund balance "of no less than two months of regular general fund operating revenues or regular general fund operating expenditures."

Today, only 64 districts of 500 (12.8 percent) in the commonwealth satisfy that recommendation, according to the state Education Department. Most districts (65 percent) only have enough savings to cover less than four weeks of expenses before service cutbacks take effect. Worse, 17 districts have no savings, and 18 have a negative unassigned fund balance. Clearly, very few Pennsylvania school districts are prepared to face prolonged fiscal crises or state budget impasses. In most cases, a revenue crisis that lasts more than three weeks will force school districts back into trimming staff, programs, and service delivery costs.

The new formula, if it is to be effective, should pay greater attention to a school district's financial condition, mainly its savings, in the same way it considers demographic and socio-economic conditions. This would help districts - especially those in poor fiscal health with little or no savings - to improve their budget flexibility and secure their schools against periods of economic uncertainty caused by recession or political gridlock.

Theodore Arapis is an assistant professor of public administration at Villanova University. theodore.arapis@villanova.edu