The start of Penn's 'Sylvania'

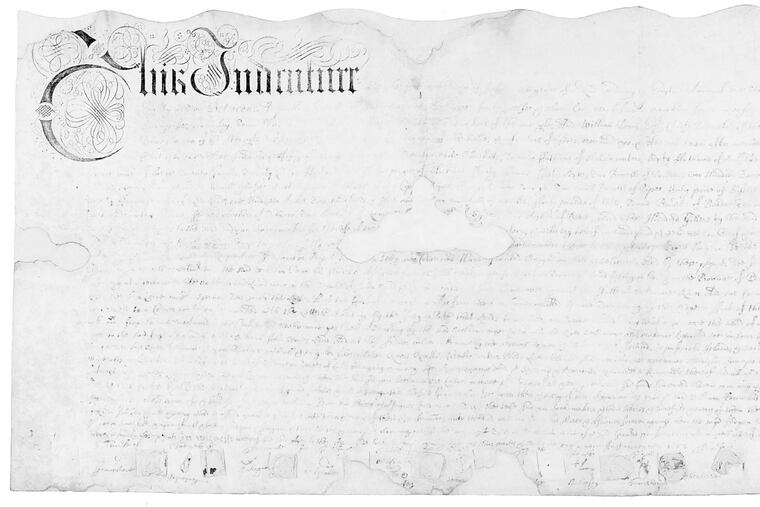

Nearly 3½ centuries ago this weekend, a pacifist became the world's largest crown-less landowner. On March 4, 1681, British monarch Charles II granted William Penn a charter for lands in the New World and "thus was a Quaker raised to sovereign power," quipped the French philosopher Voltaire.

Nearly 3½ centuries ago this weekend, a pacifist became the world's largest crown-less landowner. On March 4, 1681, British monarch Charles II granted William Penn a charter for lands in the New World and "thus was a Quaker raised to sovereign power," quipped the French philosopher Voltaire.

On this anniversary, take a nuanced look at the commonwealth's founder and founding through two items owned by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

First things first: the colony's name. Penn himself recoiled at "Pennsylvania." "New Wales" or simply "Sylvania" - Latin for woods - were his preferred styles.

Lest fellow Friends think him narcissistic, the humble Quaker pushed his royal patron to reconsider, to no avail.

A rediscovered letter from Penn to his friend Robert Turner reveals his grumbles about the appellation, and the dubious lengths he would go to have it swapped, "and though I much opposed it, and went to the king to have it struck out and altered, he said 'twas past . . . nor could twenty guineas move the under secretarys to vary the name," Penn wrote in the 1681 missive.

Put another way: Behind Charles' back, Penn tried to suborn a minister to change the province's name.

"What struck me was how much we could learn about Penn's personality and the context of his time from this letter," recounted Beth Twiss Houting, the Historical Society's programs chief, who came across it by chance. "On one hand, as a Quaker, he was mindful of vanity in not wanting his name attached to the colony. On the other, he was not beneath offering a bribe to accomplish this end."

To Penn, the 45,000 square miles represented a chance to conduct his "Holy Experiment" unmolested. Charles' motives for gifting the realm were more secular.

For the specie-starved monarch it was the easiest way to clear a £16,000 debt owed to Penn's father, also named William. That's north of £3 million in today's pounds sterling.

"No moneys were at that time more insecure than those owing from the king," Voltaire wrote in 1734.

"Penn was obliged to go more than once, and 'thee' and 'thou' King Charles and his Ministers, in order to recover the debt," he continued.

That he planned to take Friends far from the British Isles also appealed to Charles who - for his part - converted to Catholicism on his deathbed.

But the king was not about to let his coffers go unfilled by whatever valuables turned up in "Penn's Woods." The royal charter stipulated that one-fifth of unearthed gold and silver be handed over to the exchequer. The potentate also demanded "two Beaver Skins to bee delivered att our said Castle of Windsor, on the first day of January, in every yeare."

Like the letter to Robert Turner, an engraving owned by the Historical Society reveals another overlooked chapter of Penn's story: his life before converting to Quakerism.

Its called the "armor portrait" for obvious reasons. Bedecked in a breastplate, 22-year-old Penn gazes out at the viewer with earnest eyes. The then-Anglican scion is flanked by the Latin inscription Pax Quaeritur bello. This translates roughly to "Peace is sought by war," befitting his upbringing in a prominent military family.

Penn's father presumably arranged the portrait. It is believed to be one of only two likenesses drawn from life for the simple fact that - once he converted - Penn spurned having his "countenance and carriage" depicted.

(The Historical Society also owns Penn's other likeness, a pastel sketch thought to have been created without his knowledge.)

The armor portrait dates from the same year Penn joined the Religious Society of Friends, representing a unique snapshot of the young man on the verge of a decision that continues to affect today's denizens of his "greene country towne."

But before you get jealous of his luscious locks, remember that he was rendered mostly bald from a bout of smallpox as a child. Modern toupee manufacturers could learn a thing or two from their 17th-century counterparts.

These items and others documenting the history of all Philadelphians are available for research at HSP. Visit hsp.org/PlanYourVisit to get started.