Commentary: Son of Holocaust survivors asks, whither the GOP?

By David Lee Preston I'll be following the Republican National Convention this week in Cleveland with particular interest, partly because I am a child of Holocaust survivors, and partly because of my relationships with two men who are no longer among us.

By David Lee Preston

I'll be following the Republican National Convention this week in Cleveland with particular interest, partly because I am a child of Holocaust survivors, and partly because of my relationships with two men who are no longer among us.

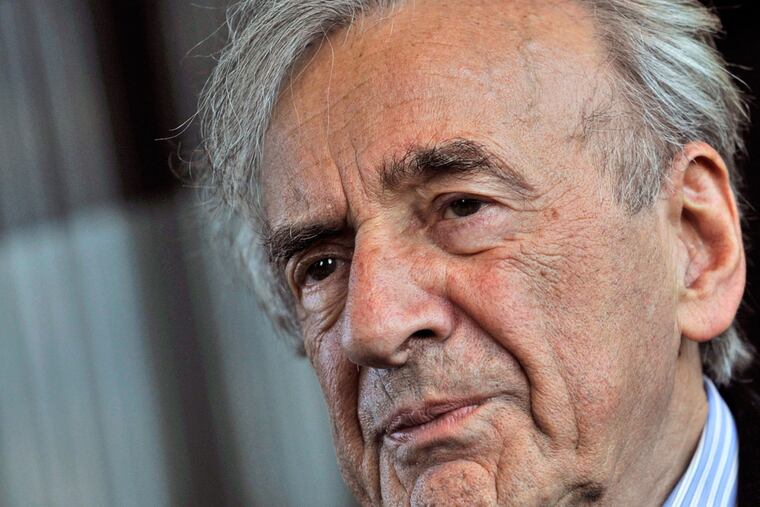

One is Elie Wiesel, the Nobel laureate who died July 2, who famously beseeched President Ronald Reagan not to visit the graves of Nazi SS soldiers at Bitburg, Germany. "That place, Mr. President, is not your place," the survivor told the Republican icon, speaking truth to power when he accepted the Congressional Gold Medal in April 1985. "Your place is with the victims of the SS." Reagan stubbornly disregarded the admonition and went to Bitburg as planned.

The other is Jerome Brentar, a Cleveland travel agent who died in 2006. Brentar was a Croatian American whom I interviewed in September 1988 about his membership in an ethnic coalition in George H.W. Bush's presidential campaign. He was a Holocaust denier and the leading supporter of retired Cleveland autoworker John Demjanjuk, who later would be convicted in Germany as an accessory to the murder of 28,000 Jews as a guard at the Sobibor death camp.

This time around, will the GOP be the party of Reagan at Bitburg, ignoring the principles for which our nation fought in World War II? Or will it be the party of Bush, his successor in the Oval Office, whose campaign dumped Brentar when confronted with hatred and bigotry in its midst?

Donald Trump's campaign has been swimming in murky waters for months. White supremacists have promoted him. He has retweeted tweets from neo-Nazi accounts. He initially refused to disavow the support of former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard David Duke. He even declined to take a stand after an article about his wife in GQ Magazine brought anti-Semitic death threats against the woman who wrote it.

It pains me to invoke Wiesel and Brentar in the same breath, but the times compel it. And I've done it before.

On Sept. 29, 1988, speaking at a program at Webster University in St. Louis honoring Wiesel, I discussed the articles I had been writing that month in the Inquirer exposing Nazi-affiliated émigrés in the Republican Party. Partly as a result of my work, Brentar and six other members of Bush's ethnic coalition were dropped from his election campaign. (That month I also had reported, in an article documenting the historic ties between Nazi-affiliated émigrés and the Republican Party, that the 1972 Nixon-Agnew reelection coalition had included three Nazi war criminals.)

Brentar, who was not an émigré but a lifelong American, told me that he doubted the accounts of Auschwitz-Birkenau survivors whom he had processed for emigration to the United States when he was an eligibility officer for the International Refugee Organization in 1949 and 1950 in refugee camps in postwar Germany.

"People were coming to me with tattoos and telling me they were at Auschwitz, but I didn't know they were survivors," he said. "When I worked there, I didn't hear of anybody telling me about gassing at Auschwitz, because they survived. To be frank with you, in Germany after the war, you were able to get any kind of identification, even an Auschwitz tattoo for a carton of cigarettes. With an Auschwitz tattoo, you were able to go around getting more from the Germans than they already got."

The day before the Webster event, I had appeared with Brentar on WOR Radio in New York. On the air, he was unrepentant, referring to the "so-called Holocaust" and calling its survivors "pathological liars."

As a reporter, I absorbed all of this without telling Brentar or the radio audience about my personal background. I'd written articles about my parents in the Inquirer Sunday Magazine in 1983 and 1985. Wiesel phoned me twice at home to encourage my work. Two years earlier, on Sept. 7, 1986, Wiesel was there when I addressed 1,500 members of the American Gathering of Jewish Holocaust Survivors in the grand ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York, sheepishly raising my fist to acknowledge a standing ovation after presenting a "letter" to my late mother.

Like Wiesel, my father had survived Auschwitz-Birkenau, where on his arrival Nov. 3, 1943, a number was tattooed onto his left forearm, 160581, the number that he displayed without self-consciousness or shame on the beach or at the swimming pool as I grew up. Like Wiesel, with the Russian army approaching, he was evacuated to Buchenwald in January 1945 and was liberated there by Allied troops that April.

My mother survived 14 months in the sewers beneath the city of Lviv. Like Wiesel, she devoted her postwar life to teaching the lessons of the Holocaust. After her passing in 1982, my father also began to speak about surviving what he called the "Industry of Death."

Now they are gone: my parents, and most of the survivors who applauded me in New York, and, alas, Wiesel too. July 2016 has already been a bloody month for our nation and our world. In Cleveland, and soon in Philadelphia, conscience and history hang in the balance.

David Lee Preston is an Inquirer, Daily News, and Philly.com editor. dpreston@phillynews.com