Why I thought twice before saying #MeToo | Perspective

For #MeToo to be worth it, the result can't just be that we make ourselves feel bad by revisiting painful memories and hearing stories that reveal the depth of our own denial.

When women and some men started sharing their stories of sexual harassment and assault on social media using the hashtag #MeToo, it almost didn't occur to me to join in. Of course, I've been sexually harassed, starting when I was a freshman in high school and continuing to the present day. As a female journalist with a Twitter feed and an easily accessible email address, I've come to accept handling a stream of sexually inflected insults as an occupational hazard. But when my Facebook and Twitter feeds filled up with other people's stories, I began to feel exhausted by the prospect of sharing my own. I don't need the catharsis, not personally. And though it would be wonderful to change someone's mind or open his or her eyes, that's just not enough. Not anymore.

The impulse behind the #MeToo hashtag is the same one that animates so many of our bitterest debates today. Those of us who know for sure that sexual harassment is real because we've experienced it are trying to convince others who have been lucky enough not to have the same experiences that those experiences are, in fact, real. This can be a crazy-making conversation. When someone insists that you haven't, in fact, lived through what you've lived through, it's easy to vacillate between rage at that person's denial and destabilizing doubt. But it's also an essential conversation: Unless a lot of us can agree on the basic fact that widespread sexual harassment exists, we're going to have trouble moving on to the next, vital phase — which involves figuring out what to do about it.

Related: How many sexual-assault hashtags does it take to end sexual assault?

And that's where things get really difficult. Consciousness-raising moments such as #MeToo, or previous hashtags such as #YesAllWomen or #WhatWereYouWearing, or Anita Hill's 1991 testimony before Congress about the sexual harassment she said Clarence Thomas subjected her to, or the 1971 "Rape Speak Out" organized by the New York Radical Feminists are opening salvos in the fight against sexual harassment and sexual violence. But they are entirely insufficient to end these problems on their own.

Moments of new awareness have often led to genuine improvements in law and culture. Two 1979 court cases helped advance the movement to treat marital rape as a crime rather than as an assertion of a man's ownership of his wife. Hill's testimony encouraged sexual harassment victims to file complaints with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and helped dissolve opposition, including from the White House, to a bill that helped those victims pursue damages, back pay, and reinstatement to their jobs if they had been terminated. Time and time again, brave women have opened the necessary space for change, and time and time again, those around them have made some progress. They just haven't made nearly enough.

Related: Instead of boycotting Twitter, here's how you can support Philly women

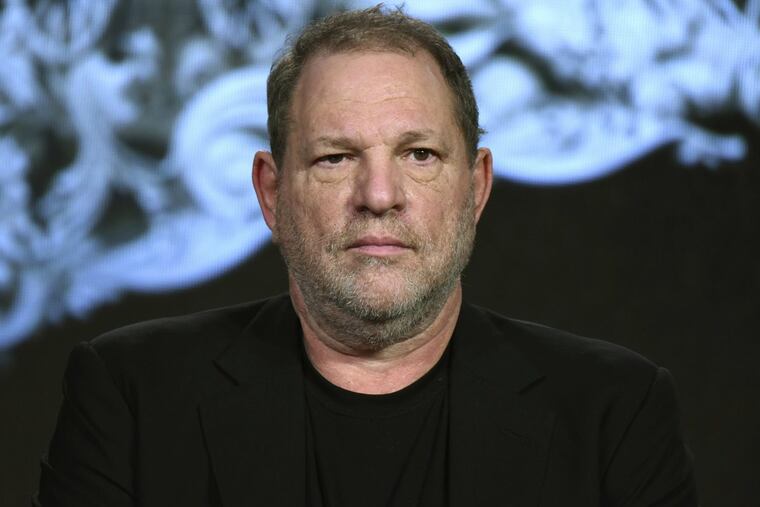

Now, the moment created by the alleged depredations of Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Roger Ailes, Bill O'Reilly, and even Donald Trump raises the question of what we will do in this generation. Will lawmakers crack down on the practice of forcing employees who come forward with sexual harassment allegations into confidential arbitration proceedings rather than letting them seek jury trials for their claims, as Ailes tried to do after Gretchen Carlson accused him of harassment? What about the confidential financial settlements that Weinstein used to silence accusers? These provisions are intended to prevent companies from the grievous exposure that the Weinstein Co. is currently experiencing. But they also deny the public a close look at the rot that eats away at organizations that tolerate this kind of behavior.

More narrowly, will the entertainment industry end the practice of conducting meetings in hotel suites? Will Weinstein be just the first person expelled from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for his conduct, the beginning of an industry-wide house-cleaning? Or will he also be the last, his downfall a fig leaf for larger inaction? What can Hollywood do to assure that no producers, directors, or studio heads become so powerful that their desire to prey on the most vulnerable players in the business is tolerated as the cost of doing business?

Related: Been sexually harassed? Philly women say #MeToo

And as daunting as these challenges are, they don't even get to the deeper questions: How does someone like Weinstein convince himself that this is normal, that this is fine, that "I'm used to that" and therefore this must be all right? At what point do people decide they can just take what they want? And how can we possibly stop them before they get there?

I don't know the answers to these questions or the outcome of these legislative fights. But I do know that for #MeToo to be worth it, the result can't just be that we make ourselves feel bad by revisiting painful memories and hearing stories that reveal the depth of our own denial. All this pain needs to turn into concrete action, or we'll be back here again in 20 or 30 years — and the stories we tell then may be even worse.

Alyssa Rosenberg blogs about pop culture for the Washington Post's Opinions section.