The 'moral hazard' of Narcan in the opioid crisis | Opinion

Grim results from a new study: "We find that broadening Naloxone access led to more opioid-related emergency room visits and more opioid-related theft, with no reduction in opioid-related mortality."

In the 1960s, after some prodding from Ralph Nader, government regulators began a major push for safer cars. Which made University of Chicago economist Sam Peltzman wonder just how much safer these innovations made us. Specifically, he wondered about what economists call "moral hazard" — our tendency to take more risks when we're insulated from the costs of that risk-taking.

In 1975, Peltzman published an article innocuously titled "The Effects of Automobile Safety Regulation." His conclusion, however, was explosive: "Data imply some saving of auto occupants' lives at the expense of more pedestrian deaths and more nonfatal accidents." Less fearful of accidents, drivers were piloting their vehicles more recklessly, substantially reducing the lifesaving benefits of the regulation. Economist Gordon Tullock suggested that if regulators really wanted people to drive more safely, they'd require automakers to mount a spike in the middle of each steering wheel, pointed toward the driver's chest.

The "Peltzman Effect" doesn't mean, however, that auto safety is useless. Drivers may be a little more reckless, but there's still been a steady decline in deaths per 100 million miles of driving. In 1965, that number was 5.3. It is now 1.2.

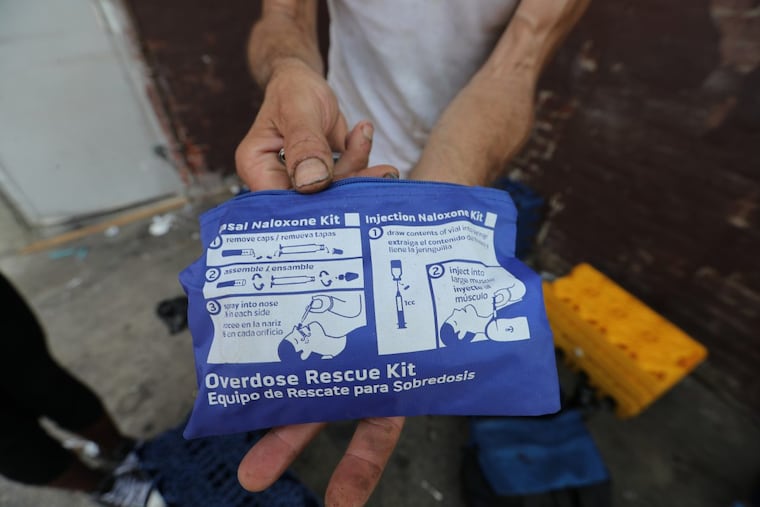

But it seems there may be one area where the Peltzman Effect not only exists but is large enough to completely erase the benefits of a safety measure: opiate use. A chemical called naloxone acts as an "opioid antagonist" — which is to say it reverses the drug's effects on the body. It can thus save people who have overdosed.

As opioid usage has worsened in the United States, more jurisdictions have acted to increase access to naloxone. Not only first responders but also friends, family, and even librarians have started to administer it. These state laws were passed at different times, giving researchers Jennifer Doleac and Anita Mukherjee a sort of natural experiment: They could look at what happened to overdoses in areas that liberalized naloxone access and compare the trends there with places that hadn't changed their laws.

Their results are grim, to say the least: "We find that broadening naloxone access led to more opioid-related emergency room visits and more opioid-related theft, with no reduction in opioid-related mortality."

You can never assume that the results of one study, however well done, are correct. But these results look pretty robust. If they hold up, they would mean that naloxone is not saving lives; all we're doing is spending a lot of money on naloxone to generate some increase in crime.

It makes a certain amount of sense that the Peltzman Effect would show up particularly strongly in drug users; after all, drugs hijack the brain's reward system, redirecting it toward drug-seeking even at high personal risk. Drug users, one would think, would be highly likely to recalibrate their risk-taking so that the risk of death remains constant, while the frequency and potency of drug use increases.

The coldly logical response to this would seem to be to discontinue naloxone use. But there's something repulsive about that conclusion, and Doleac and Mukherjee can't bring themselves to go there. "Our findings do not necessarily imply that we should stop making naloxone available to individuals suffering from opioid addiction," they write, "or those who are at risk of overdose. They do imply that the public health community should acknowledge and prepare for the behavioral effects we find here."

Sally Satel echoes Doleac and Mukherjee, both on the moral hazard of naloxone and on whether access to it should continue. Satel, a psychiatrist who is also a drug policy scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, says the paper's findings reinforce what she has heard from patients: "Patients occasionally tell me that having naloxone on hand has served as insurance against overdose. So, in some instances, it enhances risk-taking."

"That said," she emphasizes, "we must use it to save people in the immediate term."

So how can public policy prepare for those "behavioral effects" found by Doleac and Mukherjee? Satel suggests we look at civil commitment for patients who overdose multiple times in a short period. But she also notes that civil commitment can't work without good treatment options — and in a lot of places, those aren't available.

Which brings us back to something that's easy to forget about the Peltzman Effect: It can be used to argue as much for more regulation as for less. Insurance companies, after all, have been fighting moral hazard for centuries, which is why they reward people who install burglar alarms or fill in their swimming pools (or punish people who don't do those things). And so, too, can the government — for example, by aggressively ticketing speeders, passing tougher drunken driving laws, or using a combination of carrots and sticks to help addicts get clean. There are better policy responses to moral hazard than mounting a spike on the steering wheel — or depriving addicts of a second chance at life.

Megan McArdle is a Washington Post columnist and the author of "The Up Side of Down: Why Failing Well Is the Key to Success." @asymmetricinfo