‘An argument that made no sense at all’: Why Ed Rendell supported needle exchange during the AIDS epidemic and safe injection sites today | Perspective

The arguments then against the syringe exchange echo the argument that are raised today opposing overdose prevention sites. History vindicated Rendell and ACT UP.

On Tuesday, former Gov. Ed Rendell announced that he is incorporating a nonprofit, called Safehouse, that will work to open a safe injection site in the city. Responding to a recent threat by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein that federal law enforcement would crack down on a site if one were to open, Rendell told WHYY: "My address is in the offices of the Bellevue and he [Rosenstein] can come and arrest me first."

This isn't the first time Rendell has volunteered to be arrested.

In July of 1992, then-Mayor Rendell signed an executive order authorizing the establishment of a syringe exchange program — a measure to prevent the transmission of HIV. At a news conference announcing the order, the city's health commissioner at the time, Robert Ross, said that "if anyone is arrested for needle exchange, [Rendell] wants to be the first in line."

In the nine months since city officials gave a green light to private entities to pursue the establishment of a safe injection site, there has been an ongoing debate in the city about their merit — or overdose prevention sites, as Safehouse calls them. Those opposing argue they are illegal, will increase drug use and crime, and challenge the evidence that they prevent overdose deaths.

We've heard these arguments before.

During the AIDS epidemic the city engaged in a similar debate around syringe exchange programs.

The early 1990s were brutal for the city. According to the Philadelphia Department of Health, in 1991 more than 500 people died of AIDS and more than 10,000 were diagnosed with HIV. Chris Bartlett, executive director of the William Way LGBT Community Center and an AIDS activist with ACT UP in the early '90s, remembers those years as heartbreaking. "People were dying frequently, so we were all attending funerals on a regular basis."

"By the time I became mayor [in January 1992] the AIDS epidemic was a huge issue," Rendell told me this week. "Over the years I assumed that AIDS was mostly transmitted by sexual activity," he said, but it became apparent that "a significant amount of people got sick from dirty needles."

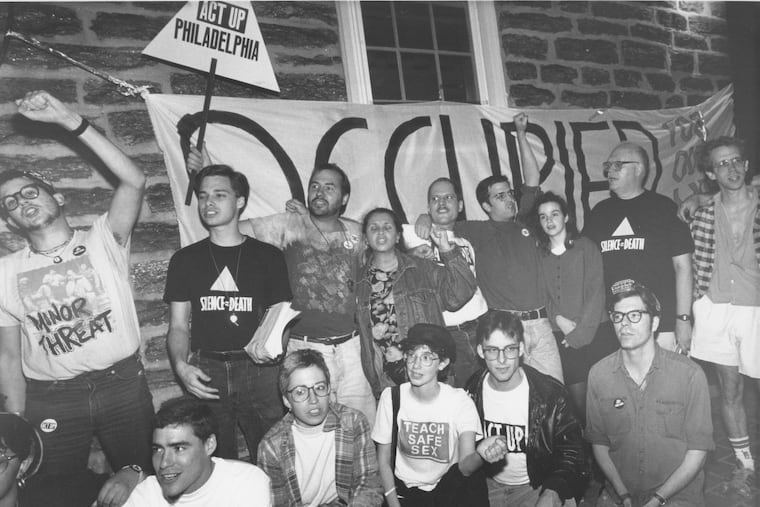

ACT UP members were looking to address the transmission of HIV through shared syringes, according to Bartlett, and started pushing for a syringe exchange program.

In 1991, a group of activists from ACT UP started giving away syringes in Kensington under the name Prevention Point. "We had folks in the movement who were injection drug users who could explain to us where advocacy was needed," Bartlett says, explaining the choice of starting the exchange in Kensington. Mayor Wilson Goode wrote the activists a letter expressing his "wholehearted support for the establishment of a needle exchange program." Syringe exchanges existed in a few other cities and there was some evidence to show they prevented HIV transmission — which in those years meant a death sentence.

Not everyone was on board. The arguments then against the syringe exchange echo the arguments that are raised today opposing overdose prevention sites. History vindicated Rendell and ACT UP.

Rendell says the first argument was that the exchange would increase crime in the area around it because its clients would stick around and commit a crime. "From my experience as [district attorney] and assistant DA I thought that that was an argument that made no sense at all." Another argument was that the exchange would enable and increase drug use. "I rejected that because common sense tells you that no one will become an addict because someone gives them a clean needle."

Rendell found the evidence about the effectiveness of exchanges compelling — both in lowering transmission and connecting people with treatment programs.

The possession and distribution of syringes without a prescription in Pennsylvania was — and is — illegal under state law. According to Rendell, "the state health commissioner said that they would arrest people who were involved in Prevention Point." To give the activists cover, Rendell signed the executive order on July 27, 1992. "I thought that by offering myself as the first person to be arrested I would probably dissuade [state law enforcement]."

The arrests never came. Looking back at the 26 years of Prevention Point, Rendell says that the exchange is "a universally acclaimed success and none of the supposed downsides ever really existed." Councilwoman Maria Quinones Sanchez, who represents Kensington, agrees. "I think they [Prevention Point] are a national model," says Sanchez, who has expressed concerns about overdose prevention sites.

According to Jose Benitez, the executive director of Prevention Point and a board member of Safehouse, since Prevention Point opened, the proportion of new HIV cases that were attributed to shared needles dropped from almost 50 percent in 1991 to 5 percent in 2017. Prevention Point also connected about 700 people to treatment last year, helped open two shelters for 80 homeless people, and flooded Kensington with naloxone — the opioid overdose reversal medication.

One of the main learnings for Benitez from the 26 years of Prevention Point is that interventions such as overdose prevention sites and syringe exchanges have to be tied to social and medical services — from treatment to housing. "We also learned that we have to be better neighbors," and indeed Prevention Point goes out to pick up dropped syringes in the neighborhood and provides access to the free medical care for neighborhood residents regardless of whether they use drugs.

Benitez called Prevention Point the "child of ACT UP Philadelphia." In this sense, Safehouse is ACT UP's grandchild. It is incumbent on our city to welcome it and to help it replicate the success of its ancestors' success — saving lives.