In 1777, a British general made a big strategic error: Trying to conquer Philadelphia | Philly History

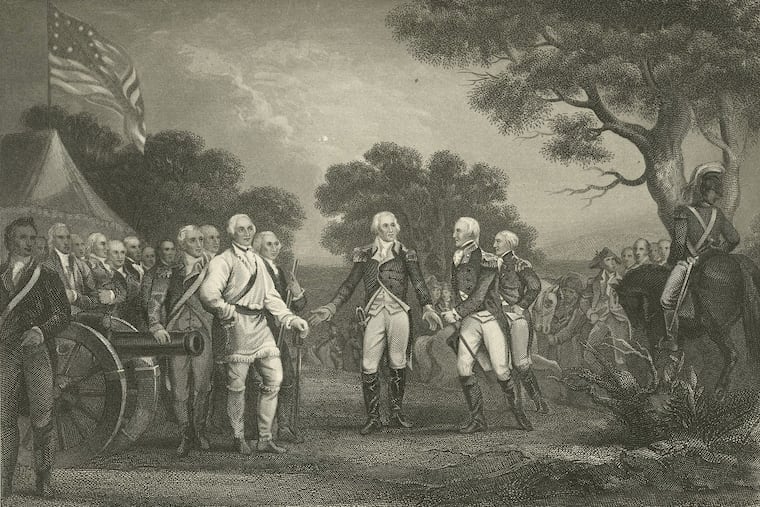

General William Howe's strategic error contributed significantly to the outcome of the Revolutionary War.

Two hundred and forty years ago this month, the British fled Philadelphia. The city served as the seat of power in the fledgling United States, and its fall in September 1777 provided a symbolic victory for the British as they sought to crush the Continental Army. The decision to take Philadelphia, however, cost the British dearly, and ultimately proved to be one of the greatest blunders of the Revolutionary War.

The idea of occupying Philadelphia diverged sharply from British military strategy in early 1777. After two years of conflict, British leadership sought to divide the Continental Army and conquer New England. Two armies were key to such a feat: the forces led by Gen. John Burgoyne, based in Canada, and those led by Gen. William Howe in New York City. Instead of marching north to converge with Burgoyne, however, Howe headed south, landing 50 miles outside Philadelphia in August 1777 with 13,000 troops. He intended to take the city where the Continental Congress had declared independence from Britain the previous year.

>> READ MORE: How frustrated train conductors drove Atlantic City to build America's first boardwalk | Philly History

Gen. George Washington confronted Howe's forces during the Battle of Brandywine in early September and suffered a resounding defeat. The Continental Congress and thousands of anti-British residents fled Philadelphia shortly before Howe's forces entered the city unimpeded on Sept. 26. Washington attempted to strike back at the Battle of Germantown in early October. Though his forces mounted an admirable offensive, the British prevailed, resulting in the long retreat that would land Washington and his men in Valley Forge for the winter.

Howe emerged victorious, but faced fresh challenges as the head of British forces occupying Philadelphia. Rebels retained control of Fort Mercer and Fort Mifflin along the Delaware River, enabling militias to sabotage British supply lines and prevent resources from reaching the British and Philadelphia's inhabitants. After the well-fortified Fort Mercer rebuffed a force of Hessian infantry, British forces bombarded Fort Mifflin for five days, reducing it to rubble and killing many of the Maryland militia members garrisoned there. The remaining Continental forces stationed in the forts fled shortly thereafter, relinquishing control of the river to the British.

>> READ MORE: The Philly venues where jazz greats found their sound | Philly History

The British regained control over vital supply routes into Philadelphia, but the negative impact of the seven-week blockade lingered. Prices in the city had skyrocketed and scarcity persisted throughout the winter. Though Howe and British leadership attempted to maintain discipline among their soldiers, many looted local families and businesses, stealing horses and essential winter supplies including wood and hay. Perhaps none suffered worse than the prisoners of war kept in the Walnut Street Jail. Many Continental soldiers were starved or beaten to death, buried in mass graves dug in what is now Washington Square.

Despite the hard times experienced by much of the city's population, the British upper brass enjoyed luxury, further damaging their image among Philadelphians. Howe resigned his position in April 1778, and the British threw an extravagant soiree in his honor, replete with dancing, a feast, a gunboat salute, and fireworks.

>> READ MORE: How Philadelphia introduced circus to the United States | Philly History

Elizabeth Drinker—a diarist, Quaker, and patriot residing in the city — detailed the stark divide between the opulence enjoyed by top British officers and the hardship of the city's residents: "How insensible do these people appear, while our Land is so greatly desolated, and Death and sore destruction has overtaken and impends over so many."

The occupation of Philadelphia came to an end in June 1778. The Continental Army rebounded after Burgoyne surrendered at Saratoga the previous fall. This stunning success encouraged France to join the conflict. To cope with the worsening situation, British military leaders recalled the force garrisoned in Philadelphia back to New York City. An enormous strategic error, Howe's quest to conquer Philadelphia hamstrung the British war effort, and contributed significantly to the outcome of the Revolutionary War.

Patrick Glennon is a communications officer at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. pglennon@hsp.org