The Philly home where the Declaration of Independence was born

On May 23, 1776, Jefferson moved into the second floor of Graff's home on Market Street. There, Jefferson busied himself with his work, including the drafting of the Declaration of Independence.

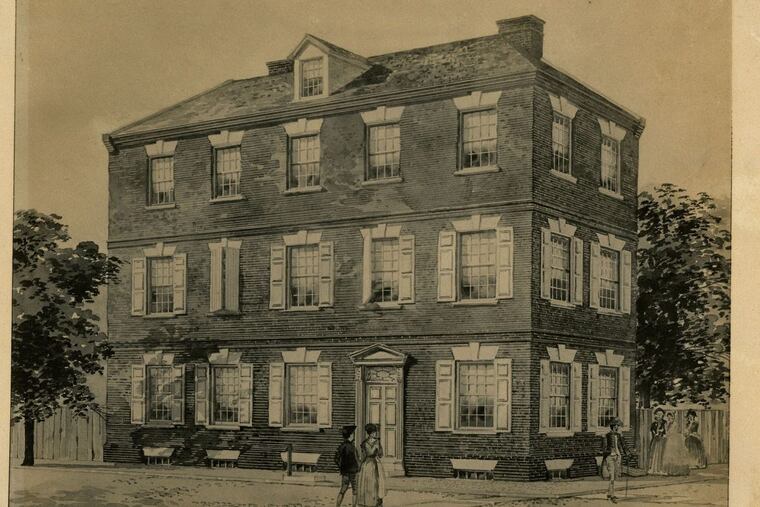

The Graff House on the southwest corner of Seventh and Market Streets is just a block a way from the heart of the Independence National Historical Park. The building was reconstructed in 1975 with federal funding to celebrate the U.S. bicentennial and pay homage to one of the most important events of the nation's founding: the drafting of the Declaration of Independence.

While the original building, also known as the Draft House, was destroyed in 1883, the National Park Service was able to faithfully reproduce much of the structure thanks to a photograph taken of the original shortly before its demolition. During the summer of 1776, in the house positioned on this very spot, Thomas Jefferson composed the document that would inspire colonists up and down the coast to put aside their differences and unify to defeat the British.

The Revolutionary War had been raging for more than a year at the time. Any hope of deescalating the conflict evaporated the previous summer when the Olive Branch Petition — an attempt at peace initiated by Congress — was turned down by King George III. The die was cast; the colonists had no choice but to pursue military victory.

Congress assigned five men to a committee to draft a document declaring independence. The project, if successful, would bind the 13 disparate colonies together, giving the insurrectionists a fighting chance against the British. If they failed, factional differences could fester, hamstringing the war effort and potentially dooming the Revolution.

Jefferson, who was renowned for his literary prowess and intelligence, was unanimously chosen by the other members of the committee — John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman — to serve as head writer for the document.

In the spring of 1776, Jefferson had resided at the home of Benjamin Randolph, a prominent Quaker and cabinet-maker who lived in the heart of the city. But when Jefferson desired a more pastoral setting to execute his responsibilities as a delegate, he chose the home of bricklayer Jacob Graff.

On May 23, 1776, Jefferson moved into the second floor of Graff's home on Market Street, which had been constructed shortly before war broke out in 1775. There, Jefferson busied himself with his work, including the drafting of the declaration, while Graff and his wife Catherine went about their quotidian existence downstairs.

All was not perfect at his Market Street retreat. Jefferson purportedly griped about the horseflies and made frequent trips to the City Tavern for libations (he maintained an account at the establishment to expedite his patronage). Still, within the quiet confines of Graff's home, Jefferson channeled the philosophies of Thomas Paine, John Locke, and scores of other thinkers to develop a compelling case for independence.

It was in this house where Jefferson most likely vented after receiving edits and comments from Congress regarding his drafts. In one letter, fellow Virginian delegate Richard Henry Lee writes, "I wish sincerely, as well for the honor of Congress, as for that of the States, that the Manuscript had not been mangled as it is." [sic] Jefferson had to deal with Congress' redaction of his attack on the slave trade, in which he rails against the "Christian King of Great Britain" for his "cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery…"

Jefferson's distaste for the slave trade, of course, did not translate into a disavowal of owning slaves. One slave, Robert Hemings, accompanied Jefferson to Philadelphia for the Second Continental Congress. Hemings likely slept in the garret of the Graff House, as was customary for personal slave servants at the time.

Jefferson moved out in September, 1776. Passing between various owners throughout the 19th century, the Graff House was ultimately destroyed to create space for the Penn National Bank. In the 20th century, the house's location briefly served as the site of a hot dog stand before its resurrection as a historical monument.

Patrick Glennon is a communications officer at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. pglennon@hsp.org