The Phila. inventor of the rock concert

Larry Platt is the coauthor of "Just Tell Me I Can't: How Jamie Moyer Defied the Radar Gun and Defeated Time"

Larry Platt

is the coauthor of "Just Tell Me I Can't: How Jamie Moyer Defied the Radar Gun and Defeated Time"

We're having lunch at Darling's Diner in Northern Liberties, one of his haunts, when he drops the bombshell.

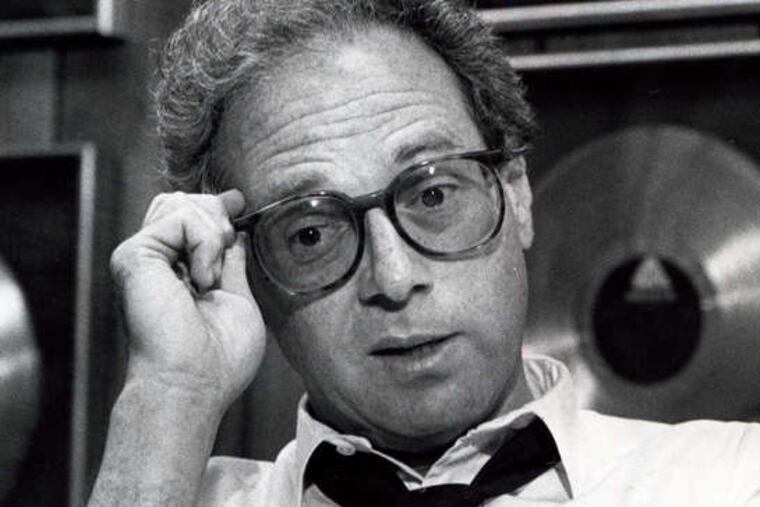

We gather here once or twice a year, at my behest, just so I can sit at a booth and soak up his tales of our city's halcyon days, when Philly changed the nation's pop-music scene, not to mention the culture itself. He is Larry Magid, legendary concert promoter and music impresario, our town's original disrupter, godfather of the '60s and '70s counterculture.

Magid's Electric Factory - first the club, then the concerts - took on the establishment in Philly and forever changed it. He stared down Frank Rizzo, mentored Bruce Springsteen, and made sure Janis Joplin had her bottle of Southern Comfort when she took the stage. He was the pied piper for a generation of kids who, in the age of Vietnam and psychedelics, were all going through a soul-searching identity crisis together.

Now, here he is, in the diner downstairs from the office in which he still produces shows, including two currently on Broadway, Billy Crystal's 700 Sundays and Beautiful: The Carole King Musical. He's 70 now, soft-spoken, thoughtful, and kindly, hardly reconcilable with the image: hard-driving, intimidating, a West Philly street-kid turned business macher in the lawless world of rock-and-roll. And that's when he mentions it:

"You'll never believe where I'm going later," he says, a mischievous smile spreading across his face. "My first meeting on the board of the Art Museum."

Wait - the countercultural icon has joined the establishment? Good for board chairman Connie Williams. That institution - like so many others - could use some of Magid's edgy marketing acumen. Truth is, he's never been as radical as people think: A longtime art collector, Magid has shown his strength throughout the years to come, in part, from the level of calm and comfort he exudes both in the presence of stoned kids and of highfalutin bluebloods. As long as you're passionate about something, as long as he thinks something stirs your soul, Larry Magid has your back.

He's never sought the spotlight, so it's easy to forget his contribution. About seven years ago, Jen and Chase Utley told me about this very cool older couple they'd met in their Washington Square condo building, Larry and Mickey, with whom they'd had dinner.

"Wait," I said. "Larry Magid?"

"Yeah, you know him?" Jen asked.

"You guys ever been to a rock concert?" I asked. Chase nodded.

"Well," I said, "he invented that."

It's not that much of a stretch. The guy reinvented an industry and helped change pop culture in the process.

He came up with "general admission seating" - we called them "dance concerts," remember? - because he said to himself: "Why do we have chairs in front of the stage? No one wants to sit down at a Stones concert."

Arena concerts? His idea, as well, though he once had to sell a young Springsteen on it, taking the Asbury Park rocker into the empty bleachers of JFK Stadium and assuring him that he could perform before 90,000 fans.

In 1969, Magid had the idea for a three-day peace-and-love rock-music festival; it was the Atlantic City Pop Festival, featuring acts like Crosby, Stills and Nash and Creedence Clearwater Revival, and it took place two weeks before Woodstock.

Live Aid? He produced it, along with that other legendary promoter, Californian Bill Graham.

Graham, who died in 1991, is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which doesn't often honor those in the live music - as opposed to the record - business. Magid isn't in the Hall, and I can't help but suspect that has something to do not only with his shunning of the spotlight, but also with where he's always chosen to live and work.

Had Larry Magid done what he's done in New York or the Left Coast, he'd be mentioned in the same breath as guys like Graham, producer David Geffen, and manager Irving Azoff - businessmen who changed pop music and the wider zeitgeist, as well.

"Larry never gets credit for being loyal to Philly," says agent and erstwhile club owner Steve Mountain, who has both competed against and been mentored by Magid. "There are a lot of personalities in pop music who say they're from Philly. . . . Larry is Philly."

I tell Magid that, if he doesn't object, I'd like to put a group together, with the aforementioned Mountain, and lobby for his Hall of Fame induction. He squirms a little. "It's not something I think about," he says. "And I don't think it's something that's going to happen."

But it should. I don't know precisely why it means so much to me that this one man receive his due. Maybe it has something to do with my hero worship of disrupters, those who say to themselves, "There must be a better way," and then go on to change entire industries. And maybe it has something to do with our town's getting its just rewards. I love the guilty pleasure that is Hall and Oates, but there's something wrong when those two Philly guys are honored with Hall of Fame induction before the impresario who laid the groundwork for them.

Here's how I look at it: Larry Magid's induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame would be an acknowledgment of Philly's key role in making pop music into a 20th-century art form. And it would be a great excuse for the most rocking, kick-ass party we've ever seen at the Electric Factory, which is saying something.

Contact me if you agree and want to help. Maybe we get a petition going.