'When I use a word," Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, "it means just what I choose it to mean - neither more nor less."

That's fine if you're an oversize talking egg in a Lewis Carroll book populated by chatty white rabbits and animatronic chess pieces. And, given his well-documented issues with balance and wall-sitting, proper usage was the least of Humpty Dumpty's problems.

But what about those two guys who are always squabbling good-naturedly about their most recent fast-food order? Or a cable-TV behemoth? Or a regional mass-transit agency?

"This is how you Sonic."

"Xfinity: The future of awesome."

"I SEPTA Philly."

What those would-be advertising catchphrases have in common is a part of speech being used in a way that accomplished lexicographers would describe, in their ponderous academic jargon, as "wrong."

Awesome is an adjective. Sonic and SEPTA are proper nouns. Yet awesome is masquerading as a noun, and the nouns are gussied up as verbs. (And using SEPTA as an action verb is problematic on another level entirely.) It all seems downright unnatural, like a grammarian's version of Rick Santorum's gay-marriage nightmare.

I know what you're saying. "So a few commercials are using words in unconventional ways. So advertisers are taking a few linguistic liberties. What's the big deal? And how on earth can you watch Pulp Fiction yet again?" (Full disclosure: I know you're saying that last sentence only if you're my wife.)

But come on. An adjective doesn't become a noun just because some ad executive decides it should be one. There are rules about this sort of thing. What if we just eliminated all the restrictions and regulations about, say, driving? You'd have people making spontaneous left turns from the right lane, or going 100 m.p.h. on the Schuylkill Expressway, or taking hairpin curves on rain-slickened roads at dangerous speeds.

OK. Bad example.

Once you start noticing this sort of unfortunate usage, you find that it's pretty much all around. On my way to work, I saw a billboard advising me that "Together we martini. Tonight we Tanqueray." Left unsaid: Tomorrow we hangover.

And a health-care giant invites people to "Live fearless." You'd think something in the Affordable Care Act could mandate Independence Blue Cross to add -ly to what should be an adverb, but apparently not. Thanks a lot, Obamacare.

This is not a new problem. Older newspaper readers - in other words, newspaper readers - might remember a famously flawed tobacco slogan: "Winston tastes good like a cigarette should." Even Fred Flintstone spoke out for the smokes, though a cartoon caveman best known for bellowing "Yabba dabba doo!" is probably impervious to linguistic criticism. (Historical note: Under pressure from the powerful English teachers lobby known as Big Grammar, the company ultimately modified the slogan to "Winston tastes good hack hack COUGH COUGH spit.")

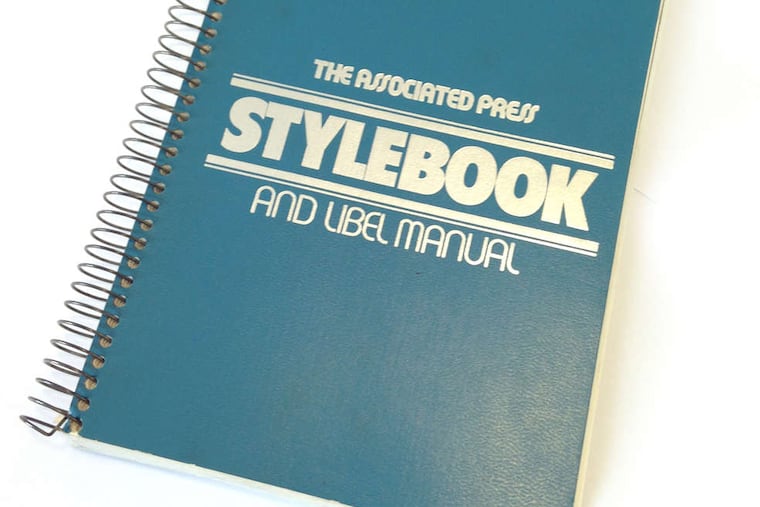

And recently, the Associated Press Stylebook - regarded as the bible for journalists, in that it's packed with arcane rules that professed adherents talk about with deference but seldom actually follow - changed its take on the word over, ruling that it can be used to mean more than in quantity, as in: There are over a million reasons this change is wrong.

The change drew protests from at least a dozen professional journalists, which represents, mathematically speaking, all of them.

But the AP Stylebook is a relic from a bygone era, when students were taught to diagram complex sentences and construct thoughtful essays, all written longhand with quills plucked from dodo birds and ink distilled from unicorn blood.

In an age of text-message acronyms and 140-character counts, the remnants of grammar and usage are worth hanging on to in whatever format possible.

Or, put another way: Together we grammar awesome.