Without a Pension's Security

Once, Americans could expect enough money to take care of themselves after a life of work. The promise was pulled away.

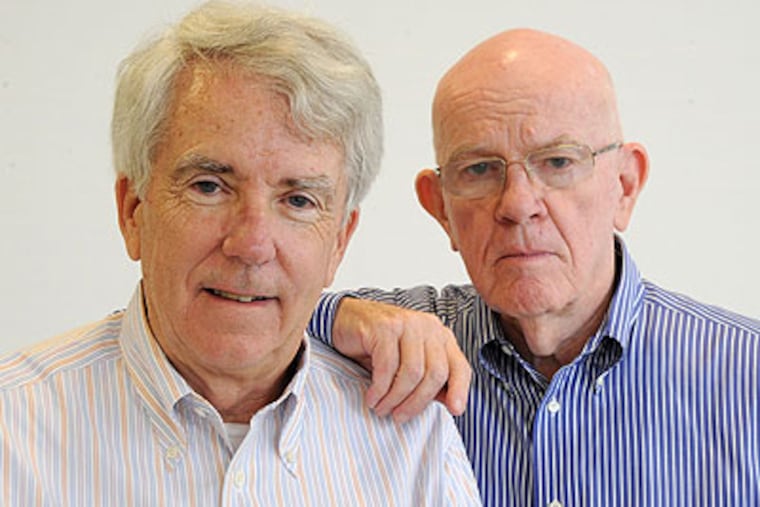

In "The Betrayal of the American Dream," Donald L. Barlett and James B. Steele revisit their 1991 Inquirer series, "America: What Went Wrong," in which they forecast a decline of the middle class. Now, they document how actions going back three decades have left millions of Americans in economic ruin. Excerpts from their book continue in Currents every Sunday through Aug. 19.

Of all the statistics that show how the rules are changing for middle-class Americans, here is one of the most alarming: Since 1985, corporations have killed 84,350 pension plans - each of which promised secure retirement benefits to dozens or hundreds or even thousands of men and women.

Corporations offer many explanations and excuses for why they are cutting down a vital safety net for Americans, but it all comes down to money. The money saved by not funding employee pensions now goes for executive salaries, dividends, or some pet project of a company's CEO. Congress went along and even compounded the betrayal by pretending that the change was in employees' best interest.

What this means is that fewer and fewer Americans will have enough money to take care of themselves in their later years. As with taxes and trade, Congress has been pivotal in granting favors to the most powerful corporations. Lawmakers have written pension rules that encourage businesses to underfund their retirement plans or switch to plans less favorable to employees.

Pensions were once an integral part of the American dream, a pledge by corporations to their employees: For your decades of work, you can count on retirement benefits. In return for lower earnings in the present, you were promised compensation in the future when you retired. Not everyone had a pension, but from the 1950s to the 1980s, the number of workers who did rose steadily - until 1985. Since then, more and more companies have walked away from pensions, reneging on their promise to their employees and leaving millions at risk.

Before today's workers reach retirement age, decisions by Congress favoring moneyed interests will drive millions of older Americans - most of them women - into poverty, push millions more to the brink, and turn the golden years into a time of need for everyone but the affluent.

For all of this you can thank the rule makers of Wall Street and Washington, who have colluded to rewrite the rules on retirement in ways that will harm millions of middle-class Americans for decades. Here is what they have done:

In addition to the 84,350 pension plans killed by corporations since 1985, companies have frozen thousands of other plans, meaning that new employees are barred from participating or benefit levels are frozen, or both. Freezing a pension plan is often the first step toward eliminating it.

The congressionally touted replacements for pensions - 401(k) plans - have insufficient holdings to provide a serious retirement benefit. This even though millions will depend on them.

As companies have killed or curtailed pensions for employees, executive pensions have soared, largely because they are based on executives' compensation - which has ballooned in recent decades.

At some companies the only employees who have pensions are the corporation's executives.

The 401(k) plans promoted by corporations and Congress that have replaced pensions as the main retirement plan for many employees are uninsured, and they are less secure and cost more to administer than traditional pensions, but they have provided a windfall of fees for Wall Street.

Workers' pensions are insured by the federal Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. (PBGC), but the agency faces mounting deficits, raising the question of whether it will be able to fully honor all pensions that may be defaulted by private companies in the future.

The ease with which companies can reduce or eliminate their pension obligations is taking a toll on workers.

Forty-nine-year old Robin Gilinger, a United Airlines flight attendant for 25 years, is very worried. Before United entered bankruptcy, she had been promised a monthly retirement check of $2,184. Givebacks arising from the United bankruptcy cut that amount in half - to $1,082, or $12,884 a year. Robin will need to work a few more years before she can take early retirement, and she wonders if even the reduced benefit will be there by then.

A resident of Mount Laurel, with her husband and teenage daughter, Robin has concerns that mirror those of middle-class Americans everywhere. In conversations with us over the past few years, she has told us that she thought of her pension as not only security in retirement, but as a safety net if something happened to her husband or she became disabled. But now flight attendants like her who have worked at the airline for years and once thought their retirement savings secure are deeply worried about the future.

The federal government, in Robin's view, did a poor job of looking out for United employees. "Our pensions were unfairly taken," she said. Since the United bankruptcy, the company has done well, she said, and even remitted payments to PBGC, but she and her fellow workers will still receive less. "This was security for us, and now that security is gone," she said. "I think the future just means working a lot harder for less."

To begin with, 401(k)s were never supposed to take the place of pensions. They were created in 1978 as a tax break for corporate executives. But soon companies discovered they could use them to fatten their bottom lines by shifting workers out of defined-benefit plans and into uninsured 401(k) plans. Proponents of 401(k)s pointed to them as more suited to a changing economy in which employees switch jobs frequently. But Congress could have revised the rules and made pension plans portable, just like a 401(k).

A total of $3 trillion is in 401(k) accounts. But look beneath that number and you'll see why they are no substitute for pensions. By 2011 the average balance in a 401(k) account was $60,329, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI). But even that modest number does not reveal how inadequate these accounts are for most Americans. Their median value was $17,686 - meaning that half the 401(k) accounts held more, and half less. Nearly one in four accounts had a balance of less than $5,000. For most Americans, the amount in their 401(k) account would pay them a retirement benefit of less than $80 a month for life.

The result is that America has become a land of two separate and decidedly unequal retirement systems - one for the have-mores and another for the have-lesses, whose numbers are exploding. Those who have less are not just the poor, whose later years have always been a struggle; now they include large numbers of the middle class-men and women, individuals and families, who once eagerly awaited retirement, but now fear what those years will bring.

People like Kathy Coleman of Ave Maria, Fla.

Like millions of others who once looked forward to that time, retirement isn't on Kathy's radar. She didn't expect this.

Kathy, some of whose experiences we first learned about through an article in the Naples Daily News, grew up in St. Clair Shores, Mich., the daughter of a tool-and-die engineer. She graduated from Wayne State University in Detroit with majors in art and interior design. She married, had two sons, and started a career in interior design. After her sons were grown and she was single again, she moved to Florida and went to work as the cultural and social events director at the exclusive Polo Club of Boca Raton. She arranged concerts, coordinated speakers and excursions for members, prepared the annual budget and monthly reports, and helped create the club's annual calendar of events.

In 2005, intrigued by a new town that Domino's pizza founder Tom Monaghan was building near Naples on the west coast of Florida, she relocated, taking a job as conference director for Legatus, an organization of wealthy Catholic business leaders that Monaghan had founded. She wrote marketing copy and articles for the Legatus website and helped coordinate the group's conferences, including an annual pilgrimage to Rome for an audience with the pope. She bought a new home in the community of Ave Maria, near the university of the same name, which Monaghan had also founded. On a quiet street, the three-bedroom house made an attractive place for her sons and their families to visit. It would also be a good place to retire.

Two years and eight months later, Kathy and some of her coworkers lost their jobs at Legatus. It was a blow that caught them by surprise. One distraught employee later committed suicide.

Kathy brushed up her resumé and began looking for work, assuming that with her years of experience in a wide range of jobs, it would be only a matter of time before she found one. But there was nothing. To make her mortgage payment and meet other expenses, she withdrew savings and started tapping into her 401(k). At a time when she would have liked to be putting money away for retirement - she was in her 60s - she had to dip into her nest egg just to keep a roof over her head. At one point she worked three part-time jobs and took an online course to become a real estate sales associate.

With her financial situation growing increasingly dire, she ultimately took a job behind the deli counter of a grocery store. The woman who had helped arrange visits to the pope was now slicing ham and cheese. She learned how to close the store for the night - how to take apart and clean the slicers, tidy up cabinets and coolers, and disassemble the metal over floor drains so they could be mopped. "I hadn't worked in anything like this since I was in my teens," she said. Eventually she qualified for the company's health plan, and in her first year she got a raise - a 15-cent-an-hour increase that put her up to $10.40 an hour.

If things had worked out differently, Kathy, 63, might be thinking of retirement.

Instead, simply holding on to her house is her most important priority. She renegotiated the mortgage and lowered the monthly payment with a 40-year mortgage. Unlike earlier generations of Americans who often left their debt-free homes to their children as an asset, Kathy will never be able to do that. Instead of saving in her later years and retiring the mortgage, she will be making payments to her bank as long as she lives if she stays in her house. Even after renegotiating her mortgage, money is still tight because her earnings are only one-third of what they once were.

Having pulled money out of her 401(k), and being in no position to replenish it from her modest earnings, Kathy is just trying to get by while she continues to look for a job in which she can use her talents and experience. In the meantime, she's focused on the present: "I'm not living in the future anymore."

While 401(k)s will provide little retirement security for most Americans, they have been a boon to Wall Street and corporate America as millions of Americans were moved out of pension plans and into 401(k)s. In almost every year since 1978, Congress has passed legislation encouraging the shift to 401(k)s, while doing nothing to shore up pension programs. The amount of money that just one industry - securities and investment - has invested in Congress over the last two decades tells the story of why the corporate world got its way.

From 1990 to 2012, the financial industry - which includes stockbrokers, investment houses, brokerage firms, and financial planners - contributed $875 million to members of Congress, mainly Republicans, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. From 1998 to 2011, the period for which data are available, the securities and investment industry spent an estimated $900 million lobbying Congress and federal agencies.

For the industry, it was money well spent. Corporations saved tens of millions of dollars by eliminating pensions, and the substitution of 401(k)s created a profitable new industry in the financial sector. Studies show that the administrative costs of 401(k)s are higher than traditional pensions, in part because there is so much overhead as a result of an army of players grasping for a piece of the $3 trillion industry. Even more distressing, the returns of 401(k)s have been, with some exceptions, inferior to those of pensions. Not to mention all the losses suffered during the great crash.

"This is what's wrong with our country," says Robin Gillinger, the United flight attendant. "I think the American public sees it, but they don't know how to stop it. We all see little things. We can see what's going on and how the well-off are manipulating what's happening to us. And there's nothing we can do. So every day you live, hoping to make change, but what change can you make? It's very frustrating."

A growing number of Americans have neither a pension nor a 401(k), and for them Social Security is their only retirement income. They must continue working well beyond 65. People like Betty Dizik of Fort Lauderdale, now in her seventh decade in the workforce. Betty never had a pension or a 401(k). After her husband died in 1968, she held a series of jobs managing apartments and self-storage facilities, but none of the jobs offered retirement benefits. Her monthly Social Security check comes to $1,200. That barely covers her supplemental health insurance, car insurance, and out-of-pocket expenses for medications to treat her heart problems and diabetes.

To buy gas for her car and pay rent, utilities, and other living expenses, Betty continued to work long after she was 65. One job provided meals to seniors; another was with H&R Block, the tax return service, where she had worked in varying capacities for 20 years until she was laid off in 2010. She has looked for work ever since but in two years she's had only two interviews, and at one she was told, "You're just too old."

She has no faith that Washington will help seniors like her because she believes Washington has no idea of the struggle that seniors go through to make ends meet. She has done it by forcing herself to live strictly within her means.

"On the third, I get my Social Security," she said. "On the fourth, I'm broke. I go on and pay all the bills and do what little shopping I have to do, and then I stay home the rest of the month. And I'm not alone. There are a lot just like me."

And thanks to the people who make the rules in America, there will be millions more like her in the future.