Decriminalize drugs, free up city jail space

Locking up the toughest could alter violent climate.

About a year ago, I was punched in the head as I walked to Temple's Center City campus. I fell down but managed to stand up quickly, and the assailant and his accomplices fled. Relatively unscathed, I continued on my way without reporting the crime.

Over the summer, I worked at a Philadelphia Freedom Schools site in North Philadelphia. One day, one of my students told me something I will never forget: "Brother Matt," the 5-year-old boy said, "I want to cut my neck with a knife."

These experiences made me realize that violence in the city is so pervasive that all Philadelphians are affected by it either directly or indirectly. And the violence cannot be reduced without changing the city's overall approach to fighting crime.

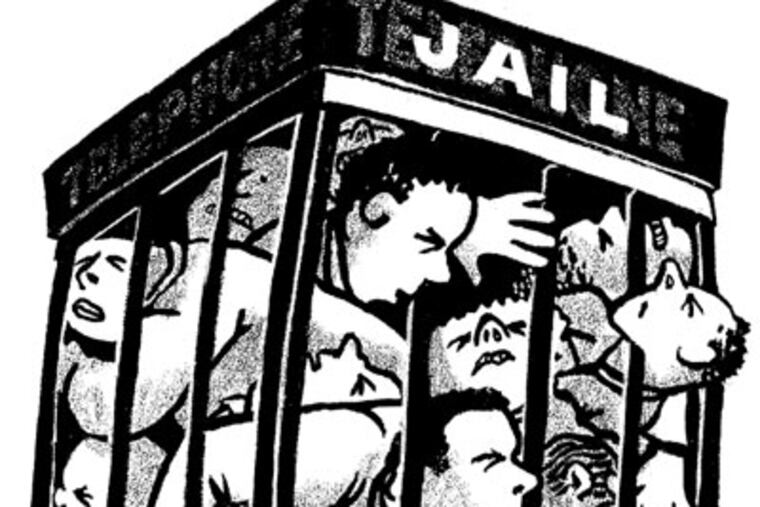

The size of Philadelphia's prison population is one barrier to significantly reducing violent crime. We should consider ways of reducing it.

One way would be to decriminalize or legalize the possession of some or all drugs. By doing so, we could ensure that many nonviolent individuals are never incarcerated, alleviating much of the strain and making room for violent offenders.

In 2005, Denver voters passed an initiative legalizing adult possession of an ounce or less of marijuana. Marijuana possession still violates Colorado and federal laws. But the Denver Marijuana Policy Review Panel, created under a 2007 initiative, recommended in a May report that the city no longer prosecute adult cases involving the possession of small amounts of marijuana.

Philadelphia officials should reflect on the possibility of taking actions like Denver's. That way, Philadelphia's police officers could use the city's resources more effectively and efficiently to reduce violent crime.

According to a report on Philadelphia's prison system conducted by Temple University researchers and released in 2006, drug offenses accounted for a quarter of all city detainees awaiting trial, 38 percent of those held on probation or parole violations, and 37 percent of those serving sentences.

The report noted that people held on drug charges made up the largest group of offenders in the city prison population "by far."

Moreover, the average annual cost per inmate in Pennsylvania was $35,140 in 2006, according to a report released by the Department of the Auditor General. So the pursuit of nonviolent drug offenders creates a fiscal burden for the city and state at a time when the money is sorely needed elsewhere.

Ultimately, Philadelphia should consider a course like Denver's and make a symbolic statement that would resonate across the nation - that incarcerating nonviolent drug offenders is costly and far less important than holding violent criminals accountable for their actions.

Philadelphia is not alone in its struggle to fight crime and accommodate prisoners. All across the country, prisons are being filled with drug offenders at the taxpayers' expense. After all, the United States does have the largest documented prison population in the world.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt reevaluated and ultimately advocated an end to the prohibition of alcohol during the Great Depression. The prohibition of drugs requires a similar reevaluation during these uncertain times.