Cosby revisited

It's hard to reconcile the accumulated accusations of sexual assault facing Bill Cosby with the charismatic comedian and pudding purveyor of yore. That doesn't mean we shouldn't try.

It's hard to reconcile the accumulated accusations of sexual assault facing Bill Cosby with the charismatic comedian and pudding purveyor of yore. That doesn't mean we shouldn't try.

The collective will to ignore these incongruous incarnations only enabled the Philadelphia native to go on about the latter chapters of his charmed career - and allowed much of the public to be blithely entertained by it - without facing the accusations.

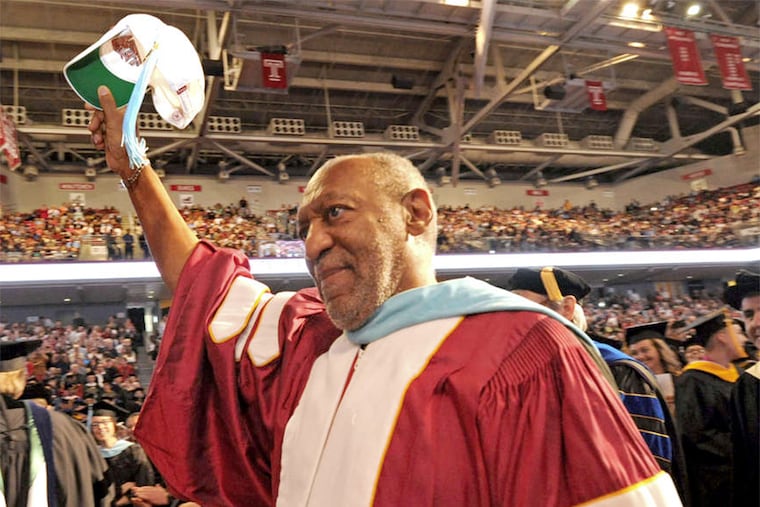

Having embarrassingly persisted in this pretense even after the rest of the country abandoned it, Temple University became one of the last major institutions to distance itself from Cosby, who resigned from its board of trustees this week. Given that Temple is one of many schools under federal scrutiny for its handling of student sexual assaults, the university was hesitant when it should have been assertive.

With his undeniable comedic genius and avuncular persona, Cosby accumulated a lifetime of rewards like his position at Temple, his alma mater. From a fund-raising post at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, to a planned return to NBC's sitcom lineup, many have been stripped from him in a matter of weeks. That befits the weight of the accusations against him and his failure to respond in kind. Cosby has not only refused to answer questions but sought to pretend they weren't even asked.

It's no wonder, considering how long that strategy worked. It's been a decade since an encounter at Cosby's Cheltenham mansion led to a criminal complaint and a lawsuit for which 14 women were said to be prepared to testify. The allegations came careening back into the public consciousness only after Philadelphia Magazine's Dan McQuade reported in October on comedian Hannibal Buress' recurring bit dismissing Cosby - known for his lectures on African American personal responsibility - as a moralizing predator.

Since then, enough women have come forward with charges that Cosby forced himself on them, often after drugging them, to bring the total to 20 over a period spanning five decades. Most were young and relatively powerless at the time of the alleged attacks. Most have made the accusations publicly and with little or no prospect of criminal prosecution or civil action. One noted that she had nothing to gain but "15 minutes of . . . shame."

If the stories are true, the shame is of course Cosby's. It's the backward but persistent impulse to blame victims that keeps sexual assaults quiet.

In one of his best early bits, a half-century ago, Cosby imagined football's kickoff-deciding coin toss being used to determine tactical advantages in historical wars. Thus the American Revolution's rebels, having won the toss, decide they will "wear any color clothes that they want to" and "shoot from behind the rocks and trees," while the British "must wear red and march in a straight line." The joke is that a few small shifts in the narrative can make the winners losers and change history.

There are few personal triumphs comparable to that of a onetime high school and college dropout from Germantown who became one of the most beloved and powerful men in America. Having achieved such advantages, did Cosby sorely abuse them? A few slight shifts in the narrative later, much of the country suspects he did, and a history of laughter and inspiration is being sadly rewritten.