Slaying the gerrymander

Public disgust with politics is widespread for good reason. Voters routinely see elected officials using power to suit their own interests rather than the public's. Pennsylvania politicians provided a blatant example when they sat down to draw new district lines for state and federal legislators in 2011.

Public disgust with politics is widespread for good reason. Voters routinely see elected officials using power to suit their own interests rather than the public's. Pennsylvania politicians provided a blatant example when they sat down to draw new district lines for state and federal legislators in 2011.

Required every 10 years as the population grows and shifts, redistricting is meant to ensure that each voting district has roughly the same number of people. Districts are also supposed to be as compact as possible, keeping neighboring communities together. But the state politicians in charge of the process used sophisticated data-crunching to juggle and squiggle district lines to favor their candidates and squelch the opposition.

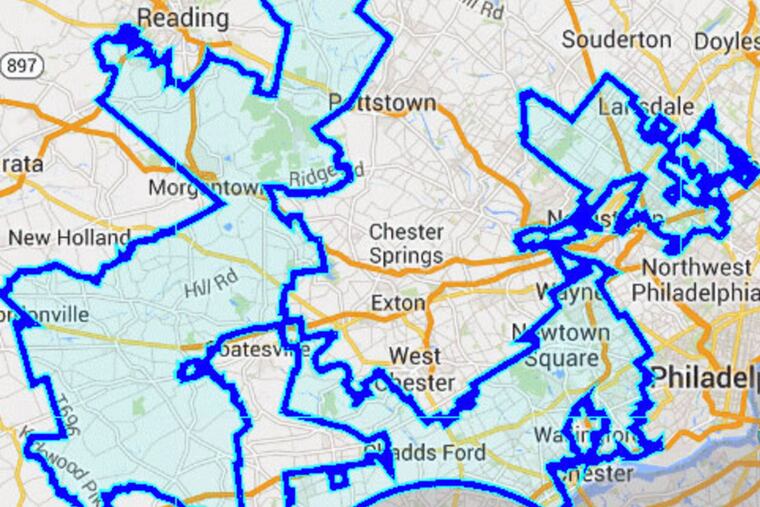

A look at Pennsylvania's Seventh Congressional District, stretching from Philadelphia's western and northern suburbs to the countryside of Berks and Lancaster Counties, shows the kind of mischief that resulted. The Seventh resembles a mutant bat, with huge, ragged wings joined by a tiny body. It made the Washington Post's list of the nation's 10 most gerrymandered congressional districts.

When Harrisburg's ruling Republicans drew their first map of new state Senate and House districts, it was so egregious that the state Supreme Court, ruling on a lawsuit led by citizen activist Amanda Holt, threw it out.

The habit is not confined to one party. The Washington Post's list of the most gerrymandered states includes Maryland, where Democrats control the process.

"We've moved to a system where legislators pick their voters instead of voters picking legislators," said Barry Kauffman of the good-government group Common Cause Pennsylvania.

The solution is conceptually simple but practically difficult: Ban consideration of partisan factors in redistricting. In Pennsylvania, that requires amending the state constitution, a process controlled by the very politicians who benefit from the current system.

The odds are long, but Sen. Lisa Boscola (D., Northampton) is giving it a try. Modeled on California's successful reform, her proposal would create a citizen-dominated panel to draw new district lines for the legislature and Congress. Panel members would be prohibited from holding political office or engaging in partisan activity for at least five years before serving. They would not be allowed to consider partisan factors such as incumbency, party registration, or past election results in drawing districts. And a supermajority of the panel would have to pass any redistricting plan.

Two leading Senate Republicans have joined six Democrats in sponsoring Boscola's reform (Senate Bill 484), so there may be hope. The legislature's Republican majority has an added incentive to support it: This month's election gave Democrats control of the state Supreme Court and possibly the upper hand in the next redistricting.

To amend the constitution, an identical reform would have to pass both the House and the Senate in two consecutive legislatures and be ratified by a statewide vote. It won't be easy. But it's the kind of change Pennsylvania needs to put power back where it belongs.