Philly plaque recalls boxer Tommy Loughran

South Philadelphians are engaged in a complex moral debate: Should a historical marker be placed outside the Snyder Avenue rowhome where Angelo Bruno, the mob boss, lived and died?

South Philadelphians are engaged in a complex moral debate: Should a historical marker be placed outside the Snyder Avenue rowhome where Angelo Bruno, the mob boss, lived and died?

Meanwhile, not too far west of there, one of those familiar blue-and-gold plaques stands at the corner of 17th and Ritner, a lonely sentinel for a nearly forgotten South Philly native and his diminished sport.

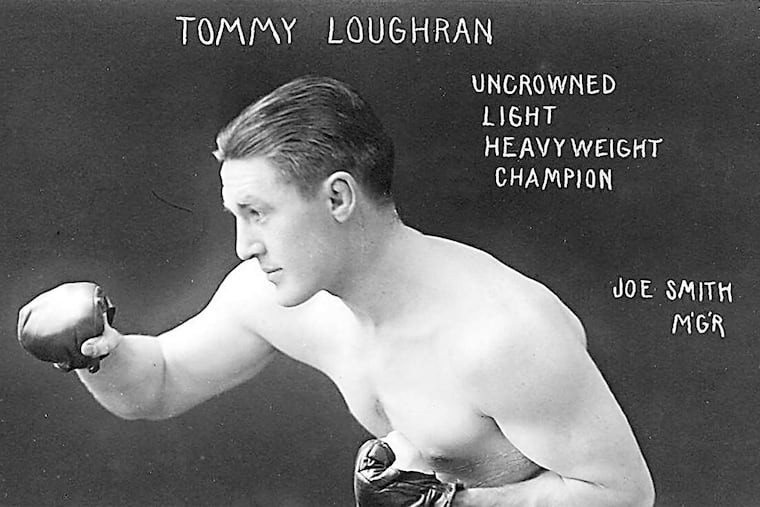

Boxing writers called Tommy Loughran, who grew up at 1634 Ritner St., the "Philly Phantom." It was a prophetic nickname. Thirty-four years after the master fighter died in a nursing home near Altoona, he's a near-invisible presence in his hometown.

Though I'd heard of Loughran, it wasn't until stumbling upon that marker during a visit to Cacia's Bakery that I was moved to learn more.

The plaque, installed in 2006, notes that he was a Hall of Famer and "a gentleman in and out of the ring." Maybe so. But, like Bruno, Loughran had to fight his way to the top.

One of seven children of an Irish motorman, he honed his muscles at the Navy Yard and in a blacksmith shop, and his craft in the gyms that filled immigrant neighborhoods like his.

Then America's second favorite sport, boxing was a way up and out for kids like Loughran. Turning pro in 1919, he fought for 18 years, winning 121 bouts and building a reputation as one of the sweet science's sweetest and most skillful practitioners.

With an unstoppable left jab and innovative defensive techniques, the blue-eyed Irishman battled successfully in three weight divisions. He won the light-heavyweight title in 1927 and retained it through six challenges, yielding it only when he moved up into the heavyweight division. Twenty-three of his opponents won championships, and he defeated most.

Ring magazine twice named Loughran its fighter of the year. That magazine also rated him the fourth-best light-heavyweight ever. In 1991, he was an early entrant into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Loughran also played a role in perhaps Philadelphia's greatest sporting event - the 1926 heavyweight title bout between Gene Tunney and Jack Dempsey, which drew 120,000 spectators to Municipal Stadium.

Tunney was a copy of Loughran, someone who favored strategy and defense over power. So it made sense when, while training in Atlantic City, Dempsey offered Loughran $5,000 to spar.

Before Dempsey's people could stop the spirited practice session, Loughran had thrashed the champion. Many, including Sports Illustrated in a much later assessment of the famous fight, blamed Loughran for Dempsey's defeat.

"I gave him such a beating," Loughran would recall. "I hit him in the belly, hit him with uppercuts, hit him with a hook. I had his eyes puffy. His nose was bleeding. He was spitting out blood. . . . He always came tearing back in no matter how hard I hit him."

Loughran defied the stereotypes of 1920s boxers. After his ring career, he went to Wall Street and became a commodities broker, specializing in the sugar market. A tough street kid, he didn't smoke, drink, or marry, all of which he saw as vices.

"I always, even as a young fellow, feared the possessiveness of women," he explained later in life. "I think marriage is a beautiful thing - for the other guy."

Even in retirement, he maintained a weight of 190, limiting himself to two meals a day. But as his health deteriorated, Loughran, who had enlisted in the Marines as a 14-year-old during World War I, moved into a nursing home for veterans in Hollidaysburg, Pa. He died there in 1982.

Now, three-plus decades later, Loughran is again the "Philly Phantom."

Most of the places where he trained and fought are gone. So are the fighters and fans who knew, admired, and remembered him.

Fortunately, like mobsters and the rest of us, great athletes scatter their DNA over a wide area. And, if you know where to look, you can still find traces of Loughran.

You can see him in grainy YouTube videos as a fighter, as a referee for Floyd Patterson's 1957 heavyweight title defense against Pete Rademacher, and that same year as a guest on the TV game show To Tell the Truth.

St. Monica's Church, outside of which his historical marker stands, still exists. The South Philly parish where Loughran worshipped and was educated has merged, though, with nearby St. Edmund's.

Surprisingly, Loughran's memory burns brightest at a suburban Catholic parish.

At St. Andrew's in Drexel Hill, the 85-year-old main altar - a grand, ornate structure of red and green marble - was donated by Loughran in 1930 to honor his late mother.

Time has obscured the connection between fighter and parish. His mother might have been a parishioner, though St. Andrew's officials can't confirm that. Or the link could have been Joe Smith, the fighter's manager and a Drexel Hill resident before his 1949 death.

Each June, during St. Andrew's eighth-grade graduation ceremonies, a student is honored for sportsmanship. The award, which includes a $50 gift, includes the following inscription:

"[This] is given each year in memory of the late Tommy Loughran . . . to the graduate who best lives the spirit of Christian sportsmanship, gentlemanliness, and the leadership which Mr. Loughran personified."

Others can judge whether a historical marker at a mobster's house is a good idea.

I'm just thankful one got erected at 17th and Ritner.

@philafitz