Rollie Massimino, the coach who couldn't quit | Mike Jensen

After his national title at Villanova, he kept going, to Vegas and Cleveland and finally the NAIA.

The last time I saw Rollie Massimino coaching, he was still Rollie Massimino, just coaching in Branson, Mo., home to the endless buffet at Golden Corral and the Andy Williams' Moon River Theatre, and also the NAIA Division II national tournament.

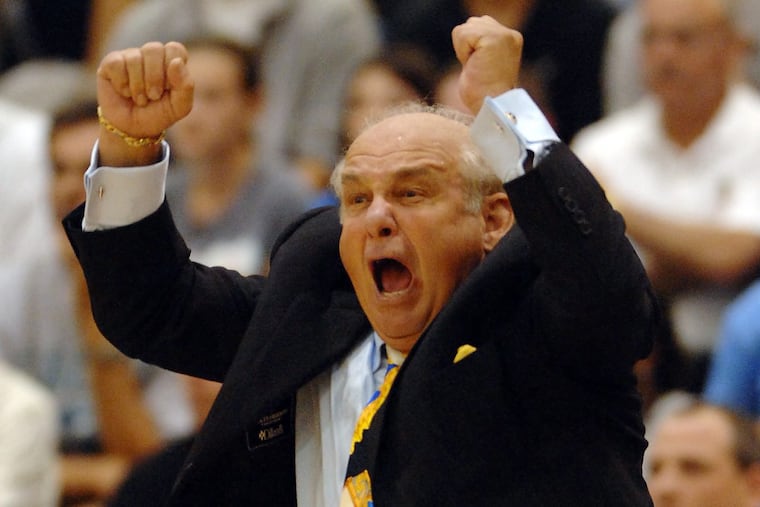

An 8:30 a.m. tipoff inside a little gym at the College of the Ozarks, March of 2010. It didn't matter. A quarter century after Massimino had coached Villanova to a national title, Massimino was coaching Northwood University at 8:30 in the morning and it was like nothing had changed. Massimino had a suit on — the only suit in the place, if memory serves — blue tie, matching handkerchief in the front pocket. Still, there were no frills to any of this.

"No frills at all," Jay Wright, who now has a national title of his own but has a hard time envisioning following that path, said that year. "He calls me sometimes. 'Where are you? ' He tells me, 'On an eight-hour bus ride from the Savannah School of Design. ' The first year they went to Branson for the national tournament, they took a bus. He's doing that at 75 years old. I can't do it now. "

Massimino did it until he died Wednesday, at age 82. Right after that national title and the other successes he had at Villanova, this was his legacy. The guy who decided not to stop. Northwood was renamed Keiser. He kept going.

I didn't cover Massimino more than a game or two when he was at Villanova, but I closely covered his fall at UNLV, which was really a push from a powerful bloc still loyal to previous coach Jerry Tarkanian. I covered his opening press conference at Cleveland State — just taking that job told everyone Massimino really couldn't quit. Then Massimino started this little program close to his retirement home in Florida since he found out golf was not enough.

Even going to Cleveland State, that had been the issue. Massimino's wife, Mary Jane, had watched the news conference from the back of the room when Massimino was introduced. She agreed with her husband that he had not been happy since leaving UNLV.

"There's only so much golf you can play," she said.

It's easy to forget Massimino was only 50 when he won it all against Georgetown. His rumpled look was kind of timeless. If you weren't with him, he didn't have much use for you. Even if you were a Villanova student putting up shots in the gym when his team was about to practice, he'd bark you out of the gym. (A buddy of mine heard that bark. He didn't find it endearing.)

You'd talk to Villanova and Cleveland State and Northwood players, though. Most said variations of the same thing. "That's my guy.'' If he believed in you, you knew it. That never changed.

Vegas was different because, well, Vegas is different. I was in Massimino's office as he cleaned it out.

"We need boxes," he shouted to someone in the outer office, still in charge the day after he announced he was leaving, a buyout negotiated. "We don't have enough boxes. "

In the midst of packing, he said, "I've been through a very, very trying experience. I've made some friends I'll cherish for the rest of my life. They embraced me."

He also pulled out a thick packet of phone messages, wrapped with a rubber band. He said Charles Barkley had called and Dick Vitale and Jim Nantz and, of course, many of his former Villanova players and assistant coaches.

The city he was actually in had turned against him, some bringing stacks of cash to the ticket office, donations if the school bought him out.

The money was right in Vegas, but nothing else. Just a weird fit. The NAIA somehow turned out to be better. That level is about the game itself and nobody ever doubted Massimino could coach the game of basketball.

"The idea of starting it from scratch, that was intriguing," Massimino said. "Helping build a gym. Build locker rooms. Order the equipment. Everything had to be done. I wasn't going to come in and take over a team. The first year, we didn't play a game. "

A vivid memory of Massimino, coaching in Branson. He was calling plays ("Four out!"), changing defenses, chewing gum with a perpetual scowl, going to one knee as the game tightened.

Northwood didn't win that morning, which meant the season was over. Massimino came out of the locker room, crumpled tissue in his left hand, shirt all moist.

"We had a chance — we were up one, 50 seconds left. The ball just didn't go in the basket," Massimino said immediately. "It was a terrific game. "

There was just one reporter in the hallway, it was the College of the Ozarks, and it was 10:45 a.m.

"It hurts just as much," Massimino said that morning.