Taking a swing at virtual reality: How Villanova baseball is using tech to improve at the plate

A university engineering professor created a system that can replicate major-league situations and help players improve pitch recognition.

Heads down, hoods up, hands buried deeply in pockets, Villanova students hustled through an icy wind that lashed their busy campus. Though it was a sunny mid-April morning, it clearly was not baseball weather.

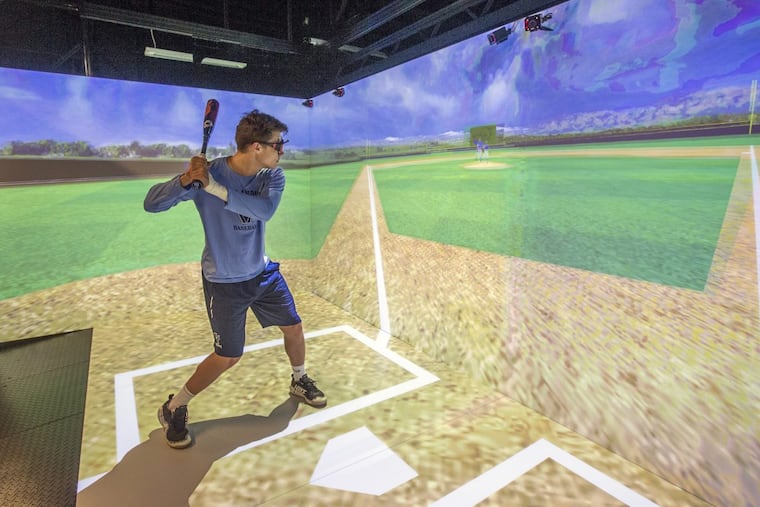

But inside Falvey Memorial Library, in a hushed, confined, first-floor corner that, while heated, wasn't much larger than a utility closet, a couple of Villanova ballplayers were taking batting practice, 2018 style.

Batting practice is a misnomer. There were no bats or balls. Instead, the Wildcats players wore virtual-reality headsets and stood in the batter's box of a 3D ballpark that had been projected onto the library's walls, trying to distinguish Justin Verlander's fastball from his slider.

This virtual BP setup — called The Cave, which stands for cave automatic virtual environment — in a technology-laden nook of the library is meant not to enhance a hitter's contact or swing, but rather to develop pitch and location recognition. It was devised by Mark Jupina, a baseball-loving assistant professor in the electrical and computer engineering department at Villanova.

"This has been an intersection of all my different interests and skills," said Jupina, a Central Pennsylvania native. "I played high school and Legion ball and coached my sons over the years. Here, I worked with [Wildcats coach Kevin Mulvey] to get a better understanding of what he and his players would like to see in terms of training aspects."

The Wildcats team, loaded with freshmen and sophomores and struggling through an 8-32 season that likely will conclude later this month, only recently began using the system.

Armed with sensors, infrared cameras, a projector, software and MLB analytics, Jupina is able to reproduce any pitch by any big-league pitcher and even augment its speed. He also hopes to incorporate the visual backgrounds of every Big East ballpark, making the batter's virtual experience even more realistic.

"Baseball is way ahead of other sports in making data available to the public," Jupina said. "That allows us to download any pitch that's ever been thrown. I can get the initial position, velocity and acceleration values for any pitch out there. So using equations of motion, we can regenerate those pitches – the actual path, the actual spin axis."

The pro-level pitches that Jupina has so far incorporated were 500 that Verlander has thrown since he arrived in Houston late last season. With 200 different fastballs and 150 sliders among them, the chances that any Villanova hitter will see the same pitch twice in a session are slim.

On this morning, freshmen Josh Kim and Sam Margulis stood in The Cave and set themselves for the Verlander pitches, each of which arrived with a shrill but slightly different whistle.

"Slider! Ball!" Margulis yelled after seeing the first pitch buzz by. "Fastball! Strike!"

Mulvey tracks the recognition abilities of each of the 31 players on the roster.

Kim is "one of our best hitters, one of the best eyes on the team. He rarely swings at a ball," Mulvey said. "And in here, he's been the best at recognizing whether it's a ball or a strike. We want to get hitters to be able to recognize that pitch sooner and sooner and sooner. You want them to say what it is, where it is,, and be right. So you keep stopping it closer and closer until they say, 'OK, I feel good. I can recognize pitches.' "

Mulvey pitched in a handful of games for the Diamondbacks and Twins in 2009 and 2010. He said the device was a tool that could benefit everyone in the game, no matter the level.

"I see this going in every single major-league clubhouse one day," said Mulvey, the Wildcats' second-year head coach. "The way BP and getting ready for a game now works is you watch film of the pitcher you'll be facing. You're not in the environment. You're just watching the film and seeing what happens. This can actually put you in that environment, facing the pitcher that you're going to see that night. You see the pitches he's already thrown. In the stadium you're playing in. Basically you're getting game at-bats before the game.

"So instead of facing a guy for a first time and saying, 'OK, I want to see what his stuff looks like tonight.' Now you'll know what his stuff looks like because you've been in here facing him and you've watched 45 pitches in the past two minutes."

MLB hitters, Mulvey pointed out, were constantly experimenting with ways to better re-create the experience of facing a big-league pitcher. Carlos Beltran, he said, used to warm up by having the pitching machine fire various colored tennis balls at 130 miles per hour.

"That's a little dangerous off an actual machine, but we can do it here in the same way," Jupina said. "If you have equations of motion and you know how to vary those parameters, then anything is possible. We could throw anything from 50 mph up to 120 mph."

Back at a classroom in the engineering building, Jupina is working on a sensor-equipped bat that, combined with other technology, would allow Wildcats hitters to swing a bat and make virtual contact with pitches.

"This could eventually be something they could bring on the road with them," he said.

The Cave, however, which was purchased for $2.6 million with a National Science Foundation grant, will stay in the library, where it's utilized by non-athletes as well. An art-history professor, for example, has used the virtual classroom to project a 3-D image of the Sistine Chapel for his students.

But a couple of times a week, it's reserved for Villanova's baseball players, who, amid the library's hush, give their eyes a workout.

"This is just the beginning stages," Mulvey said when asked if offensive improvements were yet detectable. "I think we've only had about seven or eight hitters in here on maybe five to seven occasions. But each guy that's come here has really liked and enjoyed it. They can see why it's beneficial."