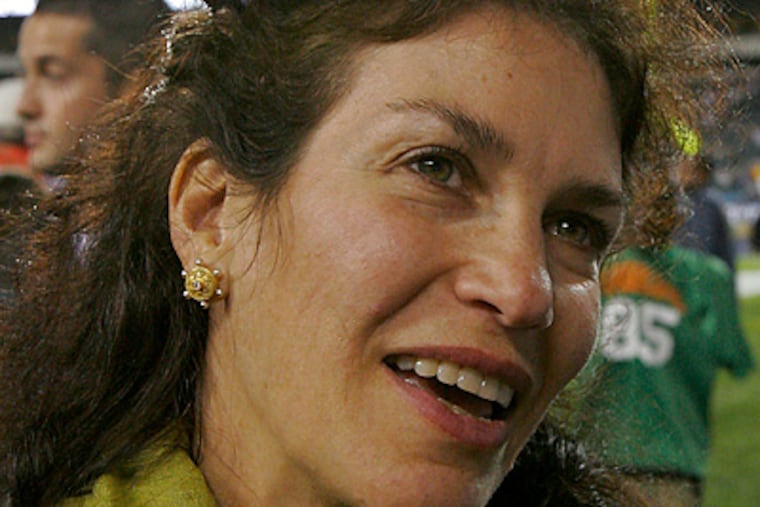

Christina Lurie helped shape the Eagles vision

Fourth of an eight-part series The wives stream by, bejeweled and Botoxed, in a high-priced parade of designer labels and expensive perfume. They are laughing, mostly, and why not? They are immaculately dressed down to their open-toed wedge sandals, not an eyelash out of place, not a fingernail chipped, and almost all are carrying boutique bags filled with Gucci and Chanel and Hermes.

Fourth of an eight-part series

The wives stream by, bejeweled and Botoxed, in a high-priced parade of designer labels and expensive perfume. They are laughing, mostly, and why not? They are immaculately dressed down to their open-toed wedge sandals, not an eyelash out of place, not a fingernail chipped, and almost all are carrying boutique bags filled with Gucci and Chanel and Hermes.

It is a charmed life, that of an NFL owner's wife. The pedestrian worries of common folks - such as how to pay the soaring electric bill or what to do once the severance payments run out - aren't of their concern. They're married to multimillionaires, and in some cases, billionaires. Those problems don't pertain to them.

But there is a wife who spurned this morning shopping trip, a diversion for the wives while the men - the highest-ranking members of the front offices of the 32 franchises - sit in a chilly boardroom discussing the business of the NFL. This woman probably would spurn the title "wife" as well, if it were not accurate. Partner might be better. For she is in the sprawling boardroom at the Ritz-Carlton in Orlando, alongside her husband, listening and learning - and, on occasion, speaking her mind.

You won't find Christina Lurie hanging with the ladies. She won't go shopping, won't go get a group pedicure, and won't go to a seminar for the wives even though the presenter is former Eagles great Troy Vincent, now a vice president at the NFL. It's just not her style.

"She's not into that. That's an understatement," Jeffrey Lurie said of his bride of 18 years. "Oh yeah, she would want to be [in the meeting] understanding what's going on with the business of football, not taking a tour of some shopping mall. If she's going to bother going [to the meeting], at least take it seriously."

That has been Christina Lurie's approach to ownership ever since she and her husband rolled into Philadelphia in 1994. Christina had a career in Hollywood. She was her own person. But her husband wanted to own a professional sports franchise, and who was she to not indulge his dream?

It might, she figured, even be fun.

Over the last 17 years, Christina Lurie has become a central decision-maker within the Eagles organization, although she makes it clear that she has absolutely zero say in football decisions - with the exception of the decision to sign Michael Vick, because there were social ramifications to that move - and prefers it that way. She didn't grow up in a football house, and she didn't pay attention to the game until it became a prerequisite to being with Jeffrey.

But everything else having to do with the Eagles? That she touches.

The logo. The colors. The cheerleader outfits. The stadium design. The practice facility. The charities. The game-day experience. The social conscience. The "Go Green" campaign. The website. Christina has played a part in all of it. She's helped build the Eagles into a billion-dollar brand.

So why doesn't she want anyone to know anything about her?

Transplants in L.A.

"I'm not going to go delving into my past," Christina Lurie says, sitting in the large conference room on the second floor of the NovaCare Complex in South Philadelphia. "Not that there's anything to hide, but just for my privacy."

Since her husband bought the Eagles in 1994, Lurie has rarely been quoted, about the family business or about herself. There's scant information available about her, and that, she says, is by design. Lurie doesn't want you, or me, or anybody else to know anything about her.

That she agreed to two interviews for this story surprised Jeffrey, who had predicted Christina would be one-and-done.

"She's very reticent," Jeffrey Lurie said.

That Christina has remained virtually anonymous is true. That she lacks an opinion is not. Her fingerprints are everywhere, including in the conference room, where reusable glass bottles hold what is affectionately known in the building as Eagles water.

Lurie has long black curly hair with a couple of sprigs of gray in it, and high cheekbones. She is toned from her daily morning ritual of yoga, and is bohemian chic in a white V-neck T-shirt, a black flowing skirt, black-patent sandals, and dark-brown painted toenails. There's a red string around her neck and beaded earrings dangling from her ears. If Lurie is wearing any makeup, it's hard to tell, but she is pretty nonetheless, in a natural, almost exotic, girl-next-door kind of way.

She was born in Mexico City, and has dual citizenship in Mexico and the United States. Lurie speaks in a blended accent that is, as she explains it, a mixture of the three languages she speaks fluently: Spanish, French (her mother's native tongue), and English. She can also get by speaking German and Italian.

Hers is not the typical look of a billionaire's wife.

The Eagles' office is virtually a ghost town. The players have scattered for their final vacation before training camp. Even the coaches, workaholics by trade, are gone. In a couple of days, the facility will officially shut down for a summer break before ramping up again for the start of the 2010 season.

For someone painted as a total outsider, Lurie's family tree has roots in South Philadelphia. Her father, Stanley Weiss, was born there in December 1926, and lived at 303 Queen Street with his three siblings, playing stickball, baseball and basketball.

"My universe as a child extended north to North Philadelphia, east to Atlantic City, west to Chester, and south to Wilmington," Weiss said in an e-mail from a vacation in Bali, Indonesia. "Although my father graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Law School, it never occurred to me if I was upper lower class or lower middle class - nor did I care. The Main Line was another world, New York and Washington different planets."

The Phillies were Weiss' team, and his passion.

"Through the knothole gang, we would watch them lose at Baker Bowl," Weiss said. "I still start each day checking how my Phillies are doing."

When he was 17, Weiss enlisted in the Army, serving most of the next 30 months at Fort Knox "protecting our gold and training in the Armored Corps for the war that was about to finish," he said. After he was honorably discharged as a sergeant in 1946, Weiss attended Pennsylvania Military College (now Widener) while starting a business. Later, he went to Georgetown.

Inspired by the 1948 Humphrey Bogart classic The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Weiss went prospecting in Mexico. "After several lean years, my luck changed," he said.

In 1960, Weiss founded American Minerals, Inc. While in Mexico, Weiss' wife, Lisa, gave birth to a daughter, Lori Christina, and a son, Anthony.

"Christina, fortunately, inherited her mother's looks, grace, and gift for languages, among other interests," said Weiss, who in 1982 founded Business Executives for National Security, a national organization in Washington that works to help the Defense Department, Department of Homeland Security, and various intelligence agencies. "As a child, she was adorable. Still is."She also likely inherited her father's understanding of the world. Lurie said when she travels to Asia, she routinely takes her Mexican passport out of safety concerns.

About the violence in her hometown, Lurie said: "It's so sad. I don't know. It doesn't look promising. The drugs and the drug lords and the corruption. It's really scary there."

Christina Lurie - she changed her name from Lori Christina Weiss to Christina Lurie after she got married because Lori Lurie sounded too weird - lived in Mexico City until she was 10 years old and then moved with her parents to London. She went to Yale and studied theater, then studied at Webber Douglas Academy of Dramatic Art, one of the leading drama schools in England, until, as she said, she "dropped out to go discover the world."

Lurie filmed commercials in Europe and did "lots of odd jobs to make ends meet," she said, "and then one day decided if I was really going to have a career in film, it had to be in Los Angeles."

In the acting scene in L.A., Lurie quickly decided that she was "never going to be a good actress," she said.

"For stage, you have to be really good," Lurie said. "For film, the camera has to work with you, too. . . . There was a huge competition, and there was no point knocking on doors. It was just a really hard road, and it wasn't one I was prepared to do. Plus, I was just as interested in what happens behind the camera as in front."

So Lurie went to work for Ron Moler, who owned an entertainment marketing firm called Aspect Ratio and had a side company dedicated to producing films. He produced the 1984 hit Bachelor Party.

"I ran his development for him," Lurie said, "and that's how Jeffrey and I met. We brought [Jeffrey] a project that he really liked - and they produced it and I associate-produced it with them - called I Love You To Death.

"That was the beginning of Pennsylvania, because I Love You To Death is based on a true story that happened, I think, in Allentown."

Jeffrey Lurie had been in Los Angeles for a couple of years, running his film company, Chestnut Hill Productions. His movies had not been commercial successes.

"He was very grounded, not a typical Hollywood person," Christina said. "He had good values, just a kind, thoughtful, considerate, smart person. And, he was crazy about sports. That was the only thing I wasn't sure about. He was like a sports fanatic, a Bostonian transplant in L.A."

This was the late 1980s, before DirecTV and the Internet. Jeffrey Lurie owned a satellite dish Christina estimated was 15 feet wide, except the apartment complex where he lived in Century City wouldn't let him put it up anywhere. So he would coax friends to let him install the dish on their rooftop, and then on Sundays he would go watch whichever of his beloved Boston teams was playing that day.

Christina would just shake her head.

"I thought, 'This is a bit intense,' but that was probably the only drawback that I could see," she said. "But his passion and his love for it got everybody enthused, and his friends and I sort of rallied around him. It was really fun."

Christina and Jeffrey married in Gstaad, Switzerland, in 1992 in a setting one of Jeffrey Lurie's childhood friends from Boston described as "outstanding."

"I remember there were people from all sorts of countries there," Arthur Greenberg said. "It had an international feel."

Greenberg said it was a "much more eclectic group of guests" than you'd find in his hometown of Newton, Mass.

Jeffrey's aunt, Esther Blumstein, was the couple's witness.

"It was a beautiful wedding," said Blumstein, who is now 99 and living in Palm Beach, Fla.

But shortly thereafter, Christina Lurie's life would change in a way she never could have predicted.

Learned on site

Christina knew of her husband's inner anguish. Jeffrey Lurie lost his father when he was 9 years old. Morris Lurie had cancer, and his death left Jeffrey with a void he filled with sports.

So after they married, Jeffrey approached Christina with an idea.

"You know," Jeffrey said, "one of my dreams is to own a sports team."

"I sort of looked at him, and I thought 'This will be an interesting journey,' " Christina said.

The Luries looked into buying the New Jersey Nets, were involved in the effort to put a new NFL franchise in Baltimore and lost a bidding war to Robert Kraft for the New England Patriots, Jeffrey's childhood team. In 1994, Lurie struck a deal with Norman Braman to buy the Eagles for $185 million. At the time, no one had ever paid more for a professional sports franchise in the United States.

"I don't think either of us had a clue what it meant to own a team," Christina said. "You know, he had a really strong sense of the game, and I definitely did not. I mean, I understood if you were watching on television, but having not grown up with it, I didn't know all the intricacies. But I don't think either of us really knew what it meant, especially about owning a team that's Philadelphia-based. This city is so intense about their teams, all teams - but especially, I think, football.

"It's been an interesting road. It's been a really exciting road, but it's been an interesting road. We both learned a lot on site."Like how Philadelphians love their hoagies. And how they loved kelly green. Not that that mattered.

"When we bought the team, Jeffrey and I were like, 'We can't live with the kelly green color.' "

So they changed it, crushing a fan base that identified the team with the color. It was an early example that the Luries didn't get Philadelphia.

But they would, eventually.

Meanwhile, owning a team didn't assuage Jeffrey Lurie's pain.

"I think he always felt that his father would really share this with him, in a wonderful way," Christina said. "But in the end, he did it for himself, and for us, not for anybody else."

Biggest worker bee

It is searing outside, and the asphalt is radiating the summer heat. The Eagles Youth Partnership's annual big event - the building of a playground - is in full swing at Wister Elementary School in Germantown, although the stars of the event aren't there yet.

In two hours, a fleet of buses will bring the entire Eagles team to the school. The kids will squeal at DeSean Jackson and wave to Kevin Kolb. They'll politely slap hands with Jeffrey Lurie and cheer Andy Reid.

But that's still to come. Right now, the real work is going on.

Sitting alone under a scaffolding next to one corner of the brick school, with black curls streaming out of the back of a white hat, Christina Lurie is painting a color-by-numbers mural, designed by the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program. She's wearing a white T-shirt, shorts, and Tory Burch flip-flops, and she has a dab of purple paint on her cheek.

"She's been here all day," says Sarah Martinez-Helfman, the executive director of the Eagles' charitable arm. "I can't get her to stop painting. Christina is the biggest worker bee here."

The Luries started Eagles Youth Partnership in 1995 as a way to give back to the community. Although Jeffrey Lurie is the chairman of the organization, Christina Lurie is the president with the vision. Each year through its eye mobiles and bookmobiles, EYP reaches 50,000 low-income children in and around Philadelphia, providing eye exams, glasses, and books.

"If you can't see, you can't read," Christina Lurie said, "and if you can't read, you fall behind. So right away we realized this was a way we could help. . . . It's easy to say 'Let's give dollars to this, this, and this. Let's think of where we can be unique and make a difference.' "

In 2003, the Eagles launched their Go Green initiative, which includes recycling, using renewable energy resources, neutralizing carbon output, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and planting trees. The Eagles use wind power at both of their facilities, and they've taken significant steps to reduce their energy consumption and trash output on game days.

In 2008, they planted 1,500 trees and shrubs in a 6.5 acre section of Neshaminy State Park in Bensalem as a way to offset the team's carbon emissions from traveling by airplane to away games.

What started as a modest recycling program has become the model for being eco-friendly in all of professional sports. And now, Lurie chairs the NFL's green club working group, a committee of club and league staff members who help determine the league's environmental initiative.

"The Eagles' 'Go Green' initiative, I believe, was the first to begin in all of sports, certainly in the NFL," said NFL commissioner Roger Goodell. "It's widely considered to be the most comprehensive in all of sports. That's a tribute to them both, but Christina has been the one focused on this."

"We have to try to make a difference," Christina Lurie said. "We have one life, and what can we do with our one life so that it's as meaningful as possible. There are many different ways of doing it, obviously. It's not just about giving back. It's about hearing what's out there, seeing what's important to me, like the environment at the moment. I mean, it's a tragedy what's going on in the Gulf. I don't even know where to begin."

Lurie also was instrumental in changing the Eagles' colors from the traditional kelly green and recreating the logo. She helped with some aspects of the design of Lincoln Financial Field and the NovaCare Complex. It was her idea to have a "heroes wall" in the lobby of the practice facility, with tributes to Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, and Jonas Salk, and to have Vera Wang design the uniforms the cheerleaders wear.

"She was very involved in our branding, with the look and the feel of anything that faced the public and our fans," said Mark Donovan, the Eagles' senior vice president of business operations from 2003 until 2008 who is now chief operating officer of the Kansas City Chiefs. "She was very involved in the website, very involved in our publications, and television. She wasn't limited to just activism.

"She's got a good eye. She really does. She's pretty definitive in the sense she either likes it or she doesn't, and she let's you know why. And, she'll let you come back and say, 'Well, here's why we think this makes sense,' and she can be convinced if there's logic behind it. She's like Jeffrey. She wants to know why, challenges it. If you have a legitimate reason why, then she'll say, 'OK, we believe you, trust you. Go.' "

As much as her husband, only in different ways, Christina Lurie has helped build the Eagles brand into the goliath it is today.

"I know you wonder where do I fit in with football stuff," Lurie said. "I don't. I don't weigh in on any football decisions, because that's not my area. But where I do feel my area is is the culture of the organization. . . . Where can we make a difference as a team? So Andy [Reid], Joe [Banner], Jeffrey, Howie [Roseman] deal with [making] the difference on the field, and I deal with [making] the difference off the field."

The middle road

This past spring, Christina Lurie went to Bhutan, a kingdom of 810,000 people in southeast Asia, just north of India, that prides itself on its gross national happiness.

Lurie was born to Jewish parents, but her father, Stanley Weiss, said it was a Georgetown professor "whose Thomistic theology had the greatest personal influence on me."

"In a word, it was sinful not to use our God-given mental, physical, and spiritual potential to the fullest," Weiss said. "I have tried to pass on this philosophy, this way of life, to Christina and her brother."

Lurie said that her only formal religious experience came in London from her Catholic nanny, who took Christina to church.

So after she had children - a daughter and a son, whose names she doesn't want made public - Christina told her husband he was responsible for their religious upbringing. A non-practicing Jew, Jeffrey Lurie did nothing. No Hebrew or Sunday school. No bar mitzvah or bat mitzvah.

"He didn't feel strongly about it," Christina Lurie said. "I think he feels culturally Jewish, and he loves some of the holidays, like Passover, but that's about as far as the religious education went."

Their first December together in Los Angeles, Christina brought Jeffrey a Christmas tree and decorated it with toasted bagels. Now, the Luries celebrate Passover and exchange presents with their children on Christmas, and that's it.

More than any other religion, Christina identifies with Buddhism. She practices yoga every morning, is essentially a vegetarian, and tries to live her life "of the middle road," she said. "Nothing is black and white. I try to live in the present, and that's pretty much what Buddhism stands for."

That's why she went to Bhutan. She had gone to India when she was 20 years old and was supposed to go to Bhutan then, but the friends in her traveling party got sick.

"As I stood in [New] Delhi, I thought, 'I'm not going on my own to those countries,' " Christina said. "But it has always stayed with me as a place I wanted to go. I always wanted to go to a country where the population is 20 percent monks out of 800,000. I'm very drawn to the world of Buddhism."

Greatest entertainment

While the other owners' wives were shopping in Orlando, Christina Lurie was in the boardroom, listening and learning and offering her opinion. The commissioner wanted her there to articulate the franchise's position on a particular football-related issue.

"She knew how her football people felt about an issue," said Goodell, who, like Lurie, wouldn't disclose what the issue was. "And, she could express it very well. She had a strong view of it because she was reflecting what they had thought and what was necessary for the Eagles.

"She's an active participant, one of the few spouses that does come in the room. That is a unique partnership, and the way [the Luries] want it."Eagles president Joe Banner, who attends the annual NFL meeting, estimated that seven of the 32 teams have a woman in the room, either as a top executive (in the case of San Diego and Oakland) or as an owner (in the case of New Orleans and Cincinnati). Each team is represented by several people, usually at the very least including the owner, the president, the general manager, and the head coach.

In 1994, Christina Lurie shelved one career - making films - and began another. She wasn't sure then where she would fit in, but it was important to her that she have a voice and purpose.

"I had to learn a lot about football," Christina said. "And, we had to figure out how we were going to create a championship team, get a new stadium, all the things that needed to happen to make the Eagles successful. So, within that arena, I was able to construct my own path, and I had total freedom from Jeffrey to figure out where I could fit in and where I could be supportive, and we were constantly exchanging ideas.

"So no, I wasn't worried. Plus, for me, owning a team is like a production. On any given Sunday, it's a production, just a different kind of production. One was film. One was football. And football is the greatest entertainment. We had to figure out how do we make it as entertaining and as good a product as possible. That was very much what we both wanted to have and see done."