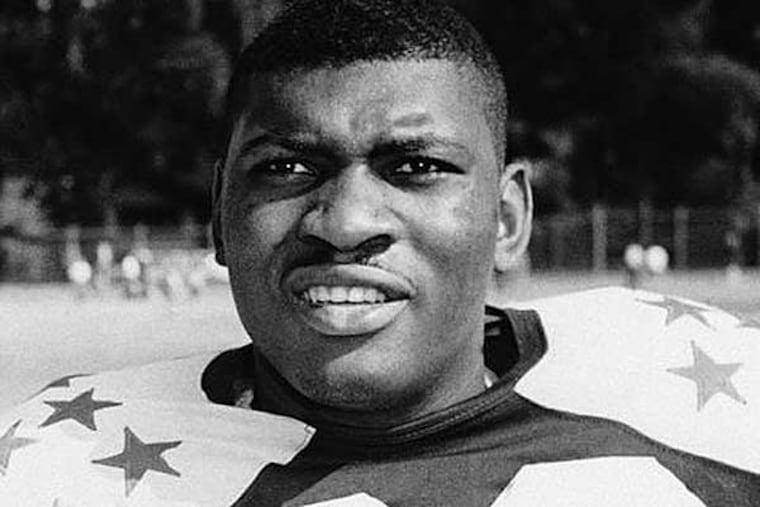

South Jersey's Dave Robinson awaits word on Hall of Fame

The details of Dave Robinson's life were made for a Hall of Fame plaque. Superstar athlete. Racial pioneer. Engineering graduate. Character in a Broadway play. Number 1 NFL draft pick. Starter in Super Bowl I.

The details of Dave Robinson's life were made for a Hall of Fame plaque.

Superstar athlete. Racial pioneer. Engineering graduate. Character in a Broadway play. Number 1 NFL draft pick. Starter in Super Bowl I.

He played for Vince Lombardi and a young Joe Paterno. Countless teammates won great fame (the legendary 1960s Green Bay Packers) and at least one earned eternal shame (Jerry Sandusky).

But there are two discordant notes in the Mount Laurel native's story, notable holes in his heart and his resumé.

One of those could be corrected Saturday in New Orleans, where Robinson waits to learn if, at 71, he has at last been elected to Pro Football's Hall of Fame.

The other isn't so easily remedied. It's the absence of his wife, Elaine, who died in 2007, and without whom, Robinson said, a Hall of Fame honor won't mean nearly as much.

"We spent 50 years together," Robinson said this week. "We dated for six years and were married for 44. I know the Hall of Fame would have meant a great deal to her. That's why I have mixed emotions about it. I'm anxious to see if I get in after all these years, but I'm so sorry she won't be here."

Their devotion was so deep that Robinson said if the NFL hadn't asked him to be in New Orleans for Saturday's pre-Super Bowl Class of 2013 revelation, he'd prefer to have experienced the news at his wife's grave in Cinnaminson.

To many, it's surprising to learn that Robinson hasn't already been enshrined in the Canton Hall, not far from Akron, where he's lived and worked the last several decades.

A two-time all-pro linebacker on Lombardi's great Packers teams, the 6-foot-3, 235-pounder was a prototype of the modern outside linebacker - fast, strong, smart and agile.

The long Hall snub might be the result of the company he kept in Green Bay. Robinson played on on a defense whose fellow left-siders included Hall of Famers Willie Davis, Herb Adderley and Willie Wood. The middle linebacker was another legend, Ray Nitschke.

Surrounded by all that talent and playing on the defensive side opponents desperately wanted to avoid, his statistics likely suffered. Robinson finished with 27 interceptions and 12 forced fumble recoveries, but stats such as tackles and forced fumbles were not yet recorded officially.

He did play in three Pro Bowls, was first-team all-NFL between 1967-69 and was named to the NFL's all-decade teams for the 1960s. Still, the self-effacing Robinson was content to stay in the shadows while his better-known teammates shared the limelight.

"It's safe to say that Robbie was a little overlooked, that he didn't always get the notice he deserved," said Packers teammate Jerry Kramer. "There were a lot of great players on those Packers, but he was certainly right there among them."

Number 1 pick

Robinson went to Moorestown High, where he was first-team all-state in basketball and baseball. He probably should have earned the same honor in football since, as a two-way lineman, he paced Moorestown to an undefeated season as a junior in 1957.

From there, Robinson went on to Penn State, where he earned a civil engineering degree and was an all-American tight end/defensive end for coach Rip Engle.

Robinson felt the sting of the Jim Crow South in 1962 when the senior was the only African American on Penn State's travel squad.

On the way to the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Fla., the team's plane had a stopover in Orlando. A restaurant there refused to serve him. Though an angry Engle ordered his team to eat elsewhere, Robinson feared he'd experience the same treatment no matter where they went.

Paterno, then an Engle assistant, told the player to come with him, and the two ate at a coffee shop.

"I had the feeling," Robinson said later, "that if they threw me out, they were going to have to throw Joe out, too."

The night after Penn State lost that Gator Bowl to Florida State, Robinson signed his first Packers contract for $15,000 a year.

Both Green Bay and San Diego of the American Football League had made him their No. 1 pick in 1963. He never hesitated in signing with the Packers and soon was a starting linebacker. He would win three NFL titles in 10 Green Bay seasons, the most notable in the first Super Bowl.

While there, he developed a close relationship with Lombardi. When, in 2010, the play, "Lombardi", written by Eric Simonson, opened on Broadway, Robinson was one of the characters.

In it, the Robinson character helps the writer/protagonist see the human side of the hard-driven coaching legend. "I had the honor," he says at one point, "of being barked at."

Saved the game

After having played in State College, where there were few black residents or students, Robinson found the same lack of racial diversity as a pro in the Wisconsin city.

"My wife didn't even come until my second year there," he said. "I was alone that first season."

One of his most memorable moments there occurred in the 1966 NFL Championship game victory over Dallas. In its final minute, with Green Bay nursing a touchdown lead, Dallas had a fourth and goal on the Packers 2-yard line. Robinson sensed an opening, improvised a blitz and hurried Don Meredith into a victory-clinching interception.

Afterward, Lombardi chastised Robinson loudly for not following the play that was called, then quickly hugged him and said he had saved the game.

His playing career ended in 1974 after a pair of seasons in Washington. He then worked for Campbell's Soup and Schlitz beer before opening a beer and wine distributorship in Akron.

A College Football Hall of Famer, Robinson failed to make the Pro Hall during his initial eligibility. He and Kansas City tackle Curley Culp were nominated this year as senior candidates. Up to two seniors and five of the 15 other nominees can be selected.