Norm Van Brocklin: The ghost at the NFC title game | Frank's Place

Van Brocklin's role in building a foundation that ensured the Vikings a future in Minnesota will hover in the atmosphere at the NFC championship game.

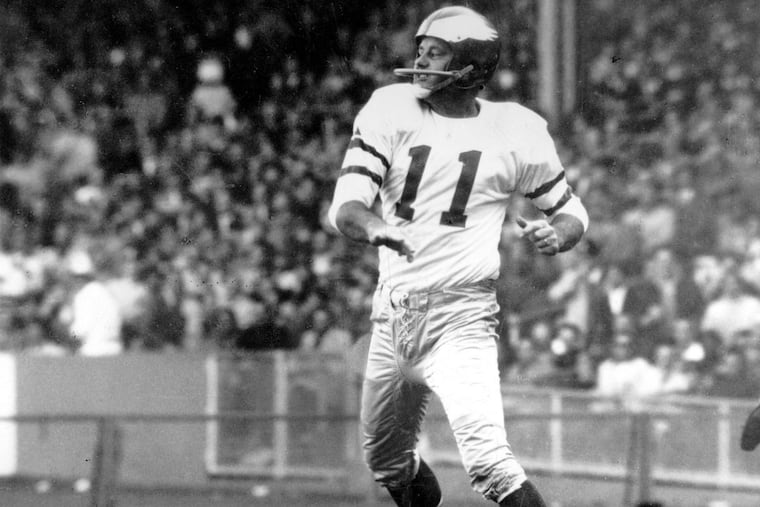

Norm Van Brocklin, Philadelphia Evening Bulletin columnist Sandy Grady once wrote, "was the pure hard metal that stays with you."

The rough-edged quarterback who guided the Eagles to their last NFL title in 1960 was a born leader with a big heart and a hard-earned wisdom. But those qualities often were obscured by profanity, impatience, and a congenital orneriness. He disliked overly analytical coaches, careless blockers and receivers, and more than a few sportswriters.

Once, discussing a late-life surgery, he characterized it as a brain transplant. "They gave me a sportswriter's brain," he said, "to make sure I got one that was never used." And when European-born soccer-style kickers became the rage, the ultra-traditional Van Brocklin urged the United States to alter its immigration policy.

Before his premature 1983 death, he'd played or coached in four NFL cities, making friends and enemies in each. Among the latter were the Eagles, who, in the days following that 1960 title, reneged on a promise to make him their coach.

If Philadelphia had honored that commitment, those decades following 1960 might not have been as arid, maybe even would have produced a Lombardi Trophy. That tantalizing what-if — and Van Brocklin's role in building a foundation that ensured the Vikings a future in Minnesota and not Los Angeles, Arizona, or Houston – will hover in the charged atmosphere at the Minnesota-Philadelphia NFC championship game Sunday.

The story of how the Eagles' next coach landed instead in Minneapolis began on Dec. 26, 1960, when, immediately after Philadelphia downed Green Bay, coach Buck Shaw retired. Van Brocklin, the league's MVP, did the same.

"He was 34. He told them he wanted to go out while on top as a player and didn't want to risk injury," said his Atlanta-based daughter, Karen Vanderyt.

He had another motive. Two years earlier, Eagles chairman Jim Clark, with the blessing of NFL commissioner and ex-Eagles owner Bert Bell, had promised the Dutchman he'd succeed Shaw.

But in the interim, illness diminished Clark and a heart attack killed Bell. Eagles president Frank McNamee and general manager Vince McNally had different ideas.

"McNamee felt threatened," said Bell's son, Upton. "He was afraid [Van Brocklin] would take over everything, which he probably would have. He always wanted to be in charge."

Several college and American Football League teams already were interested in him. So were the Minnesota Vikings, an NFL expansion franchise set to debut in 1961. For all his off-putting qualities, Van Brocklin was a natural coach, with terrific football instincts and a take-charge demeanor.

As the Eagles quarterback in 1960, he'd left home early each Monday , deposited his daughters at school, then phoned the Walnut Plaza, the hotel at 63d and Walnut where many Eagles stayed in-season.

"Get 'em up," he'd instruct the hotel operator, who began dialing the players' rooms.

At 10 a.m., they'd convene with their quarterback at Donoghue's, a drinking-man's bar just across Walnut Street.

"It was the weirdest thing," the late Tom Brookshier told the Inquirer in 1998. "Only the Dutchman could get your wife to wake you up early so you could get to a bar by 10 a.m."

There Van Brocklin guided the assembled Eagles through a day of what Tommy McDonald described as "drinking, laughing, and plotting." It worked. Philadelphia, 2-9-1 just two years before, won all but two games and a championship.

But while teammates universally respected him, they didn't all love Van Brocklin. Neither did some assistant coaches or, more important, many in the Eagles ownership consortium.

"He was very outspoken and these guys just weren't used to that," said Bell.

Van Brocklin had been so certain he'd replace Shaw that a year earlier he'd relocated from the Walnut Plaza to a $45,000 Valley Forge home. Some time on the morning of Jan. 5, 1961, at an Eagles office meeting, he realized his trust was misplaced.

Clark, his ally, was absent. McNamee was unyielding. He wanted Van Brocklin to play another season. But if he insisted the promise be honored, he'd have to be a player-coach and he'd have to retain Shaw's staff.

"That's when I knew it was all cut and dried," Van Brocklin said. "They just didn't want me."

Vanderyt recalled her father "was furious. He said he'd never trust a handshake deal again."

Less than two weeks later, on Jan. 18, the Vikings named Van Brocklin their first coach. He beat out Bud Grant, who later led Minnesota to four Super Bowls, and Sid Gilman, the brilliant but eccentric coach whose innovative philosophies had driven Van Brocklin from the L.A. Rams.

Another NFL expansion team, the Cowboys, had debuted in 1960. Even with future Hall of Famer Tom Landry as their coach, they lost every game.

At Minnesota, Van Brocklin won his first — an emphatic 37-13 thrashing of George Halas' Chicago Bears. He won it because early on he replaced quarterback George Shaw with Fran Tarkenton, even though the rookie's freelancing made Van Brocklin crazy. Tarkenton threw four touchdown passes in his pro debut.

The Vikings would win two more games – against the Colts and Rams – and drew consistently big crowds to Metropolitan Stadium. If, like the Cowboys, they'd gone winless, if Van Brocklin hadn't spotted something in a future franchise quarterback, if he hadn't established a solid foundation with the Vikings, it's easy to envision future trouble for a franchise in a city where Big Ten football was king.

The NFL, after all, was then a more fluid enterprise. The Chicago Cardinals had relocated to St. Louis in 1960, the AFL's Los Angeles Chargers to San Diego in 1961, the Dallas Texans to Kansas City in 1963.

But the Vikings stayed and thrived — even if Van Brocklin did not. He fought often with Tarkenton and quit after the '66 season.

"Dad always though Tarkenton was a self-promoter," said Vanderyt, "someone who was more interested in himself than the team."

He would become Atlanta's coach in 1968 – nearly prodding the Falcons to their first postseason, with a 9-5 record in 1973. Again he fought with players.

"He really helped solidify the Vikings and did a good job in Atlanta," said Bell. "He was good at building things but not, because he was so outspoken, sustaining them.

"In the end, he probably would have been better off in Philadelphia. Philadelphians like outspokenness."