Jagr sticks with his faith

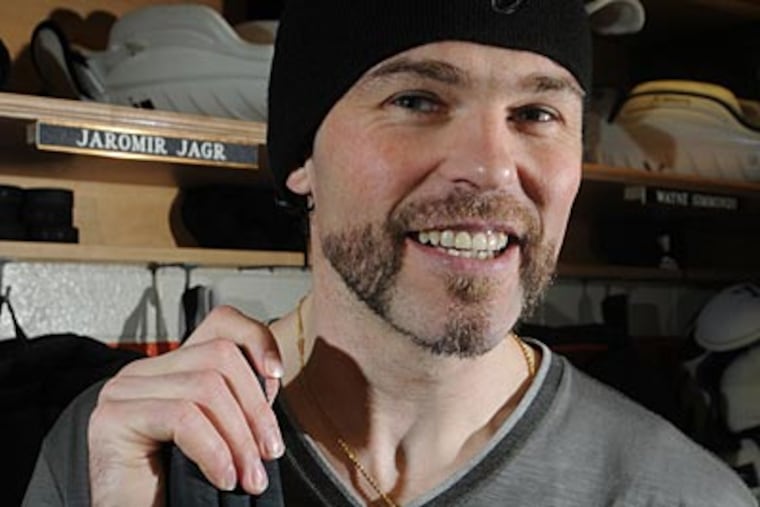

INSIDE JAROMIR Jagr's locker stall, in the bowels of the Wells Fargo Center and any arena where the Flyers play, a small memento is wrapped in blue felt.

INSIDE JAROMIR Jagr's locker stall, in the bowels of the Wells Fargo Center and any arena where the Flyers play, a small memento is wrapped in blue felt.

It is a trifold, no more than 6 inches in length. It sits next to Jagr's hockey tape, stick wax, and various weights and braces and training contraptions.

It does not stand out, except for the shine reflecting off the gilded hand-painted faces of the Eastern Orthodox Church's Holy Trinity, and the fact that religious icons in hockey dressing rooms are rarer than Stanley Cup-clinching goals.

Jagr, 40, rarely leaves home without his religious relics. He keeps one with him at most times, in his pocket or in his wallet. Jagr has a cross drawn on each of his game sticks, just under where his cocked hands perform nightly miracles of a different kind on the ice.

Hearing his Flyers teammates talk about his "religious" work ethic, you would hardly know Jagr is a man who visits church on mostly every game day, even on the road. He doesn't much talk about his faith. It's a subject even close friend and fellow Czech Republic native Jake Voracek has yet to broach with his boyhood idol.

To understand Jagr as a hockey icon, though, is to understand him as a person. For Jagr, religion is everything. He firmly believes his faith has everything to do with the reason he has not only made a Hall of Fame living in the NHL but also why he is still going strong at his advanced age. It helps explain his renaissance in Philadelphia after a 3-year absence from North America and why he is the go-to leader on a team full of kids.

"People might think I am crazy," Jagr said in a wide-ranging interview last week. "Everything in life is energy. [Albert] Einstein said it best: Energy will disappear if you transfer it to other things. If I go to church, my head is burning. It's on fire. I feel like my head is hooked up to electric steam. I feel it in my head right away, as soon as I walk in.

"It is a long process; you've got to do it 10 years, 20 years; it doesn't happen overnight. You've got to listen to your body. But you can harness that energy in your life. I don't think I'm getting old that quickly. You've got all the energy coming in your life if you ask for it. Only because of this, it's the reason I think I can still play until I'm 50."

Jagr is the Flyers' resident philosopher. He thinks the game differently and more intensely than anyone else. Jagr is obedient, but he is a free thinker. He brings his own ideas to the table, something coach Peter Laviolette says he enjoys.

Jagr's most strikingly different - and well-documented - trait is his unique workout regimen. He likes to train when most are sleeping - and it's not because he is a night owl. When he arrived in Philadelphia, he asked Flyers management for his own key to the Skate Zone in Voorhees.

"He thinks the game," Laviolette said. "He's a smart guy. When you talk hockey, or you bring out a board, or things that go on, he speaks up. He's seen a lot. He's done a lot."

Legend has it that his teammates returned from a preseason game in New Jersey in September after midnight and Jagr was skating by himself on the ice in half-darkness.

"I still do it all the time," Jagr said. "It's a lot easier. No one is bothering you, you can do whatever you want and work on whatever you want."

The security guards who keep watch over the locker room in South Philadelphia love him. Jagr is worth a few hours of overtime pay per game. More than 2 hours after most games end, Jagr and the cleanup crew are the only ones left, along with the security guards who can't go until Jagr does.

He takes his time at practice, too. After the usual hourlong skate, Jagr returns to the locker room to put on a 40-pound weighted vest and two ankle weights on his skates to go skate until his legs burn.

"When I came into the league with Pittsburgh, I liked to work out, but I didn't know how to work out," Jagr said. "Paul Coffey told me, 'You're going to do everything I do.'

"You should have seen those crazy bastards working after games and practices. It was sick how they worked. [Ulf] Samuelsson, Kevin Stevens, Rick Tocchet, Coffey. They were all insane."

To hear him explain it, Jagr's body has developed an internal voice. He knows his body's limits and when to back off.

"Most people think when you are tired, you take a rest," Jagr said. "Coffey was the one who taught me, when you're tired, that's when you've got to work harder. Since your body is tired, you aren't used to that. You'll raise the level and next time your body won't be tired.

"After the game, I'm just investing myself for next game. Sometimes, it's [bleeping] tough to do that."

Jagr drags himself through workouts after the game to feel fresh for the next one.

"The enjoyment of hockey for me is to be in such good shape that you're not struggling, so you don't feel like the game is hard for you," he said. "All of a sudden, the third period comes and you don't feel tired. When you start believing, it starts working."

Off the ice, Jagr is finally comfortable with himself.

A part of him has always been religious, but it wasn't until after he turned 30 that he recognized that fact. Jagr, a bigger Czech icon than maybe even the country's president, was not baptized by the metropolitan bishop of Prague until 2001.

Jagr's homeland used to be operated under the iron fist of communism. Religion was not practiced, since it interfered with the communist propaganda.

"They put all of the religious people in jail," Jagr said. "That's why in our country, not very many people are religious today."

Jagr's grandfather died in jail in 1968 after being locked up by the Soviet forces for refusing to work his farm for free. That is one of the reasons why he has only worn No. 68 on his jersey throughout his entire career. And the number also honors the brave period of political liberalization and rebellion in Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Voracek wears No. 93 to celebrate the powerful and peaceful split of the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1993.

(Jagr's trademarked salute goal celebration is not a military tribute, but rather because he enjoyed Terrell Davis' Mile High Salute with the Denver Broncos in the 1990s.)

It took until he left the NHL for Russia in 2006 for him to finally be more open about religion. The religious mementos in his locker are a Russian thing. Sergei Bobrovsky sets up a similar relic in his stall. Detroit's Pavel Datsyuk has been known to carry the same sacred objects.

In Russia, Jagr said, God helped him get through tough times, because "things are kind of [messed] up there."

Ask him about Alexei Cherepanov, his 19-year-old linemate and New York Rangers first-round pick who collapsed and died in his arms on the bench during a game, and Jagr fills up with tears. Ditto with the September plane crash that killed the entire Lokomotiv Yaroslav team, with many friends on board.

"When I was in Russia, I learned not to hide it and not to be ashamed of it," Jagr said. "No one hides it there. No one looks at you like you're crazy there. They need positive energy. Here [in the United States], I'm older and I don't care. But when I was younger and first came into the league, you look around to see if someone will laugh at you. When you are older, you don't worry about that stuff."

He doesn't care what his teammates think. No one has asked, he says. Jagr openly practices religion in a sport that disdains individuality.

"If it was more than three players, I'd be shocked," another player said. "Even if some of those guys went to church in that HBO episode of '24/7,' I'd bet it's the only time they've gone."

Since 1974, there has been a designated chapel in every Major League Baseball stadium for daily and Sunday ritual during the season. More than 3,000 players in the majors and minors participate every week, including notable stars such as Jimmy Rollins, Jake Peavy and even J.D. Drew.

Bible study is a weekly activity in the NFL. Eagles coach Andy Reid, a Mormon by faith, has been known to lead his team in prayer from time to time.

"Nobody really does it, not in hockey," Jagr said. "I think there are so many guys who believe in a higher power, a belief in something bigger than themselves. They believe that good things happen to people who do good things. I think most of the people in this room have that - they just need to find it."

That doesn't mean Jagr is eager to pass on his religious beliefs to a teammate.

Heck, Jagr is barely willing to share his training tips. It's not because he wants to keep them secret, but he doesn't want to take someone off his game. That is one thing that has changed in him, an added bonus Flyers general manager Paul Holmgren maybe wasn't considering when he signed Jagr to that surprising $3.3 million deal last summer.

Jagr took the Czech national team's young players under his wing in recent years. He has shared the tips, tricks and secrets from a 22-year career that has seen him become one of three players in the entire world to win the Stanley Cup, an Olympic gold medal and a world championship each twice.

"Any little advice you give someone, I believe, changes their life in some way," Jagr said. "If I give someone advice, I need to make sure that it 100 percent works. I can't be wrong."

His relationship with burgeoning superstar Claude Giroux has been nothing short of a proverbial godsend for the Flyers. Just last week, long after the Flyers had wrapped up an hourlong practice, a sweat-stained Jagr pulled aside Giroux in the hallway outside the team's lunch room.

Jagr is nearly 16 years older than Giroux. A zany skater with a mullet to die for, Jagr was already a Stanley Cup champion before Giroux celebrated his fourth birthday in 1991.

Jagr's impact on Giroux, from the workout tips to the on-ice training sessions, has been evident since Jagr's arrival. His first nickname for Giroux was "Little Mario" in honor of Mario Lemieux, but the "little" moniker quickly fell by the wayside after Giroux's 93-point regular season.

Jagr credited Giroux for wanting to be better, and Giroux soaked in all the knowledge he could from the 1,600-point scorer.

"I feel pretty special to have him around to show me the way," Giroux said. "I'm just a young kid still, I came into this league not knowing what to expect. And then I saw 'Jags,' and he's one of the hardest-working guys in the league."

The conversation with Giroux last week, one of many during that day alone, lasted more than 20 minutes. Jagr was moving his hands in all sorts of directions, as if he was diagramming a play in thin air. Giroux nodded along in agreement.

"Every practice, I learn something new," Giroux said. "I think he's learning, too. I've never had a real teacher, let alone a legend like that."

With anything in life, religion and hockey take dedication, passion and belief.

Amazingly, Jagr says if he were not a professional hockey player, he could see himself being a priest because of the strong connection between dedicating your life to your work and helping others.

For him, priesthood is not too different from his own life. Jagr has his vices. He is no choirboy. His name has made it to the gossip column once or twice in his long career. But he does not drink alcohol and rarely spends much time out.

Jagr is not married. It's not because he is not capable of love or afraid of marriage. In fact, he said love is "the greatest gift that one can give." It's just that Jagr is in love with hockey. One of his country's most eligible bachelors, he has a steady, longtime girlfriend who understands his pursuit of perfection on the ice. His ultimate goal is to make the fans happy, so he can be happy.

He says he doesn't have a wife or kids because he wouldn't be able to bring himself to leave home late at night to train at the rink - or to go on weeklong road trips. Many players juggle family lives, but Jagr does not want to take away from one to give to the other.

"I'd rather be at the rink than be at home sitting and staring at the TV," Jagr said. "What good does that do? I just know I couldn't leave if I was married. That wouldn't be right to them."

Not surprisingly, few players have done it as well as Jagr over the last 2 decades. And that's why Jagr went on his pursuit to find a higher power, to say thanks.

"Not too many people understand," Jagr said. "I've always felt differently. I've always felt like I had a big help, I know I have a big gift from someone else."