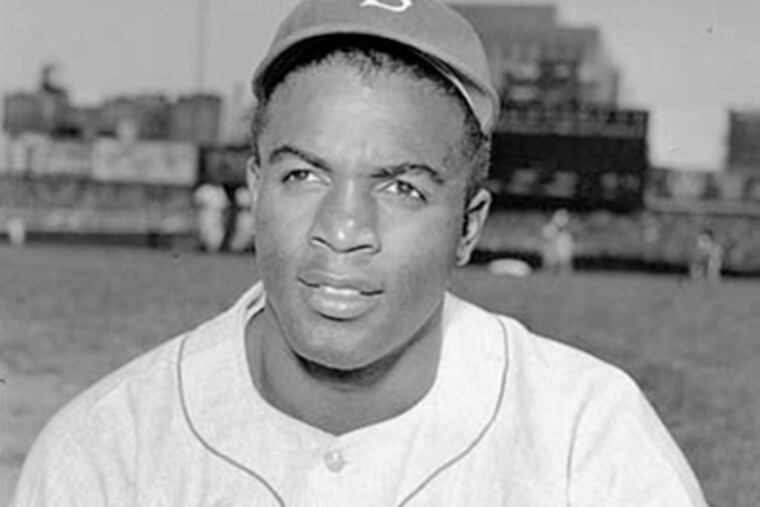

Breslin's entertaining read about Jackie Robinson

MAJOR LEAGUE Baseball celebrates Jackie Robinson today. Lots of guys wearing 42, which was Robinson's number. Newsreel snippets on the gaudy scoreboards, some of them showing Robinson stealing home, which he did 19 times.

MAJOR LEAGUE Baseball celebrates Jackie Robinson today. Lots of guys wearing 42, which was Robinson's number. Newsreel snippets on the gaudy scoreboards, some of them showing Robinson stealing home, which he did 19 times.

It's always a little awkward in this town, because in '47, the year Robinson broke baseball's color barrier, the Phillies' manager was a foul-mouthed redneck named Ben Chapman. Chapman taunted Robinson, called him something that rhymed with digger, had his pitchers throw at Robinson's defiant chin, had his infielders spike him at second base.

Robinson turned the other cheek so often that first year, they could have marketed a bobblehead figurine with Robinson's head going side to side. That's ancient history now. Or is it?

You think Barack Obama is in the White House in 2011 if Jack Roosevelt Robinson wasn't in the Brooklyn clubhouse in 1947? Just asking.

Funny thing about the annual celebration of Robinson, and what he meant to the history of the game, to the history of America . . . the people who made it possible usually get short shrift. Not this year.

Jimmy Breslin has written a taut, little book titled "Branch Rickey," about the man who defied the other 15 club owners to sign Robinson. Happy Chandler, who was baseball's commissioner back then, gets credit for ignoring that 15-1 vote by the owners to squelch integrating the game. Leo Durocher, who managed Robinson, is cited for muffling a player mutiny.

Breslin is a New York character who has made a lovely living writing about New York characters. He fancies himself as a Damon Runyon kind of guy. I have read Damon Runyon, and Breslin is no Damon Runyon. But he did win a Pulitzer in 1986, and you've gotta respect that, even if he only spoke to Rickey once, and that was as a smart-aleck kid, sitting in front of the man at a football game.

It's a skinny book, 147 pages, and it would have been skinnier if he hadn't padded it with moth-nibbled anecdotes about a daffy pitcher named Billy Loes, who once claimed he lost a ground ball in the sun.

The book breaks no new ground. It's just a swift, entertaining read, littered with one-liners. ("Baseball was a sport for hillbillies with great eyesight.")

"Branch Rickey was neither a savior nor a samaritan," Breslin writes. "He was a baseball man, and nowhere in his religious training did he take a vow of poverty."

It turns out that when Rickey sold players such as Johnny Mize, he pocketed 10 percent of the sale price. So what prompted Rickey to defy those other owners, to rewrite the lily-white history of the game, to sign Robinson, and quickly follow with Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe?

Breslin doesn't solve the riddle. He writes about a sermon the devout Rickey delivered, "announcing he was here to run the Brooklyn Dodgers and to serve the God to whom they prayed, and the Lord's work called for him to bring the first black player into major league baseball."

Six pages later, Breslin quotes Bill Shea: "He [Rickey] figured that at the least there were a million blacks who played baseball. He knew right there . . . that it was only sensible to look for players who could make the Dodgers. And fill seats at Ebbets Field and all over the league."

So, was he fulfilling some divine promise? Or was he looking for ballplayers? Or simply trying to fill those empty seats at the ballyard? Rickey's Hall of Fame plaque credits him with inventing the farm system, with running the Browns, the Cardinals, the Dodgers and the Pirates. And, oh, yeah, "Brought Jackie Robinson to Brooklyn in 1947."

Brought Robinson to Brooklyn? Paid his subway fare? It was a nickel back then. Branch Rickey first brought Robinson to Brooklyn to find out whether he had the right stuff to become the first big-league black player.

"I'm looking for a ballplayer with the guts not to fight back," Rickey barks at Robinson. That harsh dialogue has been repeated so often, it has to be true, doesn't it?

Felt the same way about Durocher's legendary middle-of-the-night monologue when he heard about a petition some Southern players were circulating saying they would not play alongside Robinson.

"I hear some of you fellas don't want to play with Robinson," Durocher yelped. "And that you have a petition drawn up that you are going to sign. Well, boys, you know what you can do with that petition. You can wipe your ass with it."

Does that make Durocher a flaming liberal? Or a cunning manager who saw Robinson as a catalyst for creating havoc on the bases, for winning games, for winning pennants?

And, as long as he's puttering around in the attic, Breslin figures he might as well settle some old scores. Rips Jimmy Powers, who was sports editor of the New York Daily News back in the day.

Identifies Powers as "the most persistent and vicious of Rickey's enemies. He delighted whites who saw blacks as not just playing baseball but also taking white men's jobs in the iron worker's union." Says Powers wrote 80 anti-Rickey columns in a 4-month stretch in 1946.

Raps columnist Joe Williams, of the World Telegram. Says Williams wrote in 1946 that Rickey deliberately lost the pennant race by trading Billy Herman to Boston "and postponing a championship until the next year, when Robinson's arrival would make it 'a Negro triumph.' "

Good stuff, good book. *

Send email to stanrhoch@comcast.net.