Johnny Callison's all-star moment erodes with time

Baseball fame, like all fame, is fickle. Sometimes it's as enduring as the game itself. Sometimes it lasts only as long as a walk-off trip around the bases. And sometimes, as with Johnny Callison, it melts away gradually.

Baseball fame, like all fame, is fickle.

Sometimes it's as enduring as the game itself. Sometimes it lasts only as long as a walk-off trip around the bases. And sometimes, as with Johnny Callison, it melts away gradually.

The expiration date on Callison's glory, much of which the late Phillies outfielder acquired as the 1964 All-Star Game's MVP, may be fast approaching.

With the Mets hosting the All-Star Game this summer for the first time since that memorable afternoon at Shea Stadium 49 years ago, Callison's game-winning home run has enjoyed a brief and sudden revival.

YouTube hits on his dramatic ninth-inning shot off Dick "The Monster" Radatz are way up. The moment undoubtedly will be replayed and discussed during Tuesday night's Fox29 broadcast of the 2013 game from Citi Field.

And just last week, ESPN.com offered a richly detailed, magazine-length article on Callison, who died at 67 in 2006, and his shining moment.

But nearly a half-century after the Phillie favorite floated around the bases and into the embrace of his star-laden team, memories of his achievement are, like the artifacts that made it possible, fraying, even disappearing.

Those who saw it live on NBC that Tuesday are aging, forgetting, dying. So are many of the fans who adored the good-looking Californian who spent all of the 1960s here. The Phillies' two subsequent world championships have diminished the focus on him and the ill-fated 1964 team. And baseball's All-Star Game has produced new heroes, new drama.

Soon, it seems inevitable, his signature feat will be confined to that place in baseball's collective mind reserved for such relics as spitballs, Connie Mack's A's, and the Polo Grounds.

In fact, that process, this 2013 All-Star Game revival notwithstanding, seems well under way.

Since his widow's death in 2010, the Phillies have lost touch with Callison's family and couldn't immediately provide contact information for any of his three daughters or eight granddaughters.

A recent RealClearSports.com list of the All-Star Game's 10 greatest moments failed to include the game-winning home run the then-25-year-old Phillie hit on July 7, 1964, to give the National League a 7-4 victory.

Worst of all, though, may be the fate of the artifacts. The ball Callison hit has been badly damaged, and the borrowed bat with which he propelled it may be lost forever.

The ball, which his middle daughter, Cindi Moore, inherited after her mother's death, was nearly destroyed by the family's dog.

"John said it was just his luck that years ago his German shepherd got a hold of that ball," said Tommy Adams, a Cape May collector and longtime Callison friend.

And while rumors persist that Callison might have given a dying child the 32-ounce bat he borrowed that day from Billy Williams, the Phillies legend always told sportswriters it was in the Hall of Fame.

"That's where it belongs," Callison said in 1996, "so everyone can enjoy it."

When contacted for this story, however, neither Cooperstown officials nor Williams himself could confirm that.

Though the Hall acknowledged having a bat Williams used in the '64 All-Star Game, it wouldn't go further.

"Billy donated a bat to us in 1974 and indicated that he used it in the 1964 All-Star Game," said Craig Muder, the Hall's director of communications. "However, he did not indicate anywhere in our records that the bat was the one Johnny Callison borrowed."

Meanwhile, a Chicago Cubs spokesman who, at The Inquirer's request, asked Williams to clear up the confusion surrounding the bat, reported that the 75-year-old Hall of Famer told him he "wasn't sure if it was the exact same bat [Callison] used in the game."

In some way, the sad story fits well with the life and career of John Wesley Callison, a five-tool player who, as longtime manager Gene Mauch once noted, never appeared to appreciate just how good he was.

Haunted by doubts

The All-Star Game home run was the mountaintop of Callison's fine career. Later that summer, his Phillies collapsed and never regained their footing. Before too long, his production - and to some extent his life - would do the same.

Callison was out of baseball before the 1973 season ended. He spent his final decades selling cars and tending bar, beset by numerous illnesses, by the painful memory of 1964, and by the self-doubts that inexplicably hounded a player who seemed to have it all.

"He talked a lot about how bad his luck was," Adams said. "He knew that if the Phillies hadn't blown that 61/2-game lead in 1964, he would have been the National League MVP instead of Ken Boyer. And who knows what would have happened after that?

"He said his luck was so bad that when he finally got well-known enough to earn a cigarette endorsement, the surgeon general banned those ads."

That existential angst might explain why Callison was unusually superstitious, even by baseball's exaggerated standards.

"I had the glove he used for much of his career," said Adams, who returned it to Callison's first male heir, a grandson, after the ballplayer's death. "It was so worn that it actually has a hole in the pocket. He told me Mauch used to plead with him to get another glove."

Like so many of this city's fans, Callison never got over 1964's trauma, when the Phillies unimaginably squandered that 61/2-game lead with 12 games to play. Like his cursed manager, Callison never got to a World Series.

"When I think back to that season," Callison said in 1993, the wound still fresh, the words still difficult to utter, "the first thing I think of is the pain."

In helping Mauch's Phillies nearly steal the '64 pennant, Callison hit .274 with 31 home runs and 95 RBIs, finishing second to St. Louis' Boyer in the MVP voting.

The 5-foot-10, 175-pounder was a multitalented outfielder. In a four-year stretch from 1962 through 1965, he averaged 28 homers, 92 RBIs, and 29 doubles a season. He was a fleet runner in a lead-footed era, a superb rightfielder, and he possessed a cannon arm.

Ill-equipped

Selected to a 1964 all-star team whose starters were Williams, Willie Mays, and Roberto Clemente, with Hank Aaron and Willie Stargell in reserve, Callison didn't expect much playing time.

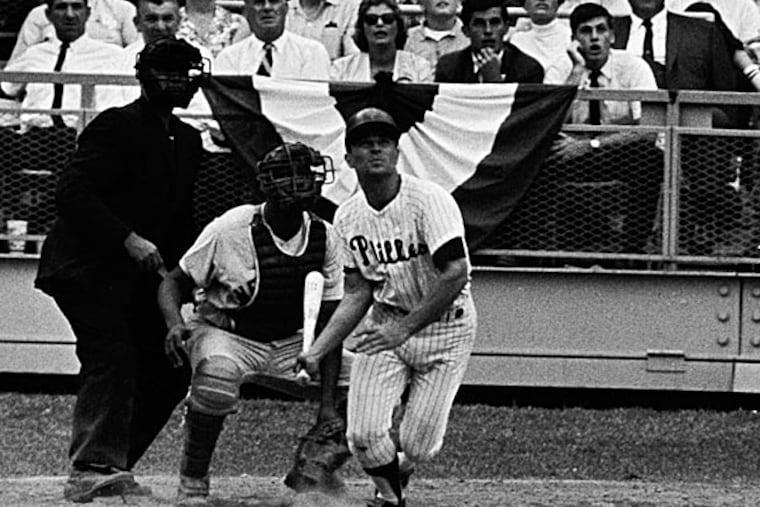

It was just as well, since the Phillies failed to get his equipment to New York in time for the game. When National League manager Walter Alston sent him up as a pinch-hitter in the fifth inning, he used a borrowed bat and Ron Hunt's Mets batting helmet.

He stayed in the game, replacing Clemente in right, and, facing Radatz in the seventh, flew out deep to Mickey Mantle in center.

In the ninth, seeking more bat speed against the hard-tossing Radatz, Callison plucked Williams' 32-ounce model from the rack.

The NL had tied the game, 4-4, and two men were on base when Radatz unleashed a high fastball. Callison turned on it. "The hardest ball I hit all season," he said. The three-run homer rocketed into Shea's right-field stands.

Callison was the game's MVP. (His youngest daughter, Sherri Curran, was given that trophy, and his oldest daughter, Lori McGowan, got the all-star ring each player was presented.)

A year later, his numbers were similar: .262, 32, and 101. But at 26, he had reached his career's peak. Never again the same player, Callison was traded to the Chicago Cubs after the 1969 season and retired four years later at 34.

Always uncomfortable

Throughout his career, as the many photographs of him in Philadelphia newspapers attest, Callison rarely looked comfortable in his own skin. Jim Bunning, who would become a U.S. senator, said his Phillies teammate never came to grips with his great ability, and "that probably caused him a lot of angst."

"I don't know if I'd say my father was never comfortable," said Moore, 53, "but it definitely wasn't his nature to look at what he'd done or who he was."

Callison, who played before free agency, earned $42,500 in his final big-league season. He had lived in a modest Glenside home since coming to Philadelphia in 1960, and retirement was difficult.

"I remember my dad said, 'What do I do now? I'm still young,' " Moore said.

He worked with a printing company, and took jobs selling cars and tending bar.

"He wasn't much of a car salesman at all," said McGowan, 55. "But I think he really enjoyed the bartending. People would remember him and want to talk about his days with the Phillies, and he loved doing that."

The ulcers Callison had battled as a player flared in retirement. In 1986, he was hospitalized when one hemmorhaged. A decade later, an aortic aneurysm nearly killed him. In his last years, there was a broken leg that made bartending difficult, plus serious heart and lung issues.

"My God," Moore said, "it was like everything went wrong with his health that could go wrong."

Through it all, though, Callison could hold onto that afternoon at Shea Stadium in 1964.

"It was a rare moment," Moore said, "but he knew what he'd accomplished."

And unlike the pennant he never won, no one could take that away.

"Whenever he talked about that, he always used to say that he was lucky," recalled McGowan, referring to the All-Star Game homer. "He said, 'Most people never get to experience their dreams. I got to live mine.' "