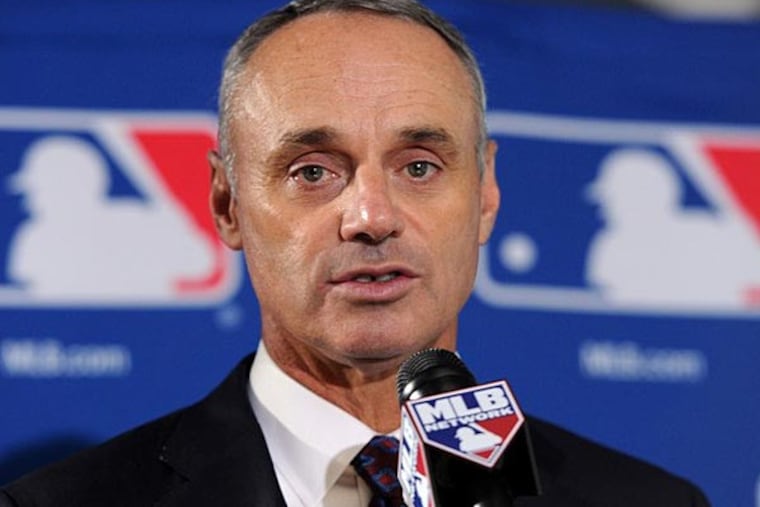

New baseball commissioner Rob Manfred faces tough decisions ahead

NEW YORK - Baseball's new commissioner was at Veterans Stadium the night before he made the least prescient statement of his life. Rob Manfred, who officially replaced Bud Selig on Sunday, was a young summer associate with the Philadelphia-based law firm of Morgan Lewis in 1981. Somebody offered him tickets to a Phillies game and he happily accepted.

NEW YORK - Baseball's new commissioner was at Veterans Stadium the night before he made the least prescient statement of his life. Rob Manfred, who officially replaced Bud Selig on Sunday, was a young summer associate with the Philadelphia-based law firm of Morgan Lewis in 1981. Somebody offered him tickets to a Phillies game and he happily accepted.

It was not just any Phillies game, either. Pete Rose had Stan Musial's National League record of 3,630 career hits in his sights. He needed one to tie and two to break it. Nolan Ryan was pitching for the Houston Astros, Steve Carlton for the Phillies. There was no better place for a baseball fan to be that night, and Manfred, 22 years old at the time, was a huge fan.

"I'm late getting out of work and I'm running like crazy to get to the ballpark," Manfred recalled.

As he stood at the will call window waiting for his ticket, the crowd of more than 57,000 erupted. Rose had led off the bottom of the first inning with a single to center field and tied Musial's record.

"I figure: no problem," Manfred said. "He's got three or four more at-bats. I'm going to see him break the record tonight."

Rose struck out in each of his next three at-bats against Ryan and finished the night a hit short of breaking the record.

"I was very disappointed," Manfred said. "I didn't see the tie and, of course, the next day [the players] went on strike."

The next morning Manfred was reading the sports page in his office when a friend from the mail room asked him what he thought about the strike.

"I like my labor relations and my sports separate," Manfred told the man.

The story makes him laugh.

"It didn't really work out that way," Manfred said.

Before the end of the 1980s, Manfred would be in a boardroom pitching negotiating ideas to baseball owners in an era when there was much contempt between the teams and the players' union. By his own admission, one of his first pitches was way outside even though he initially thought it was right down the middle of the plate.

David Montgomery, eight years before becoming the Phillies president and very involved in labor negotiations at the time, broke the news to Manfred that his pitch would be flatly rejected.

"David and I go way back," Manfred said. "He remembers the first meeting we were in together. It was a preparation session for the 1990 negotiations. We went in and made the big pitch to the Phillies on what we thought these proposals should be and how great we thought they were. They all sat there and seemed pretty positive in the meeting. I only learned after the fact that people thought we were crazy."

Montgomery remembers it well.

"We had just hired Morgan Lewis and they came up with the solution of pay-for-performance," Montgomery said. "We all knew the union would never agree to that."

Those labor negotiations eventually resulted in a brief lockout during spring training in 1990 and when the mother of all baseball work stoppages ensued four years later, causing the cancellation of the World Series, Manfred and Montgomery became extremely close friends.

"David was deeply involved in the revenue-sharing conversations that led up to the negotiations in 1994," Manfred said. "We worked very closely together at that time and during the 232 days of the '94 strike, we were kind of in the bunker together."

Manfred, 56, went from being a lawyer representing baseball to an employee of baseball - his first job was as Selig's executive vice president of economics and league affairs - in 1998. Eventually, the native of upstate New York became Selig's trusted right-hand man and in August of last year he was elected commissioner after going up against Boston Red Sox chairman Tom Werner and baseball's former vice president of business Tim Brosnan.

"I think baseball made a good choice," Montgomery said. "I think he will do well. He'll take the best of Bud and add to it. I think Bud was incredible in trying to get everybody to agree, which is why it took a long time for some things to get done. He wanted all 30 clubs to agree. I think Rob is going to say what is good for 25 or 26 is good for baseball and we'll probably see an up tempo on some of the thornier issues. I think Rob knows we need to act in a brisker manner than we have in the past."

The Phillies are in the midst of a potential organizational shake-up, with reports surfacing late last year that limited ownership partner John Middleton is trying to take majority control of the team.

"I've gotten to know John pretty well in recent years," Manfred said. "He has been coming to owners meetings and I've had a chance to get back and forth with him. David has gone out of his way to make sure I've gotten to know John a little bit. I'm very impressed with John Middleton. He knows about the game and he really, really is interested in having a great team in Philadelphia, and [is] all the things you'd want to see in an owner.

"In terms of change, that's a Phillies issue that is just not appropriate for me to talk about. But I can't say enough good things about John Middleton."

The man who was waiting in line for his ticket when Pete Rose tied Stan Musial's National League hit record 34 years ago is now the 10th commissioner in baseball's history. That means the baseballs this season will bear his signature, which Manfred admits is a "very cool" perk of the job.

Difficult decisions, however, lie ahead, including what to do about Rose's lifetime ban that was implemented by the late commissioner Bart Giamatti in 1989 and upheld by Faye Vincent and Selig, the two commissioners who followed him.

Given his allegiance to Selig, it seems unlikely that Manfred's stance on Rose will be any different. For now, he is saying little.

"Until I deal with whatever request comes from Pete, it's just inappropriate for me to say something one way or another," Manfred said.

There are issues Manfred is eager to tackle in the immediate future and one of them is the pace of game, a major problem for a sport in need of a younger audience. Baseball experimented with a 20-second pitch clock during the Arizona Fall League and will continue to do so in minor-league games this season.

"We put those clocks in Arizona Fall League games and people went and watched the games and said, 'Gee, this actually works pretty good,' " Manfred said.

The games were faster, but the AFL prospects were not all in favor of the move. The new commissioner seems to like the idea a lot.

Manfred is also not bothered that in addition to the game's all-time hits leader Rose, the Hall of Fame is also probably never going to include career home run leader Barry Bonds or a lot of other confirmed and suspected users of performance-enhancing drugs.

"Look, there is always going to be issues about Pete, Bonds, Clemens, whomever," Manfred said. "I think that's part of the process that the Hall of Fame has in place. If you were at the [Hall of Fame] induction ceremony last summer, it is really hard to reach the conclusion that the Hall of Fame has a problem. It was one of the greatest celebrations of baseball I have ever seen anywhere."

Manfred was a central figure in the Biogenesis case that led to Alex Rodriguez's 2014 suspension and has been outspoken about his stance on PEDs. Baseball came under some criticism for using paid informants in the Biogenesis investigation and Manfred staunchly defended the tactic.

"The three words I like best on performance enhancing drugs are cautious, constant vigilance," Manfred said. "I am cautiously optimistic about the great progress that we have made. I think the game is cleaner than it has ever been. I don't like the way baseball looks if players are using performance-enhancing drugs."

Manfred has inherited a healthy industry. According to Forbes, baseball's gross revenues in 2014 were a record $9 billion, a rise of more than $6 billion since Manfred became a full-time employee of Major League Baseball in 1998.

Now, after 23 years of the Bud Selig era, Manfred is in charge of moving the game forward.

@brookob