How a baseball painting launched a culture war | Frank's Place

The exhibition seemed harmless. It linked sports and art, two disparate aspects of an ideal America that the 1950s would soon come to represent.

I can't remember what drew me there. Maybe it was the promise of warmth. Maybe I was dragged unwillingly. Most likely I was trying to impress someone with the ounce of wisdom I'd acquired as a college freshman that crazy autumn.

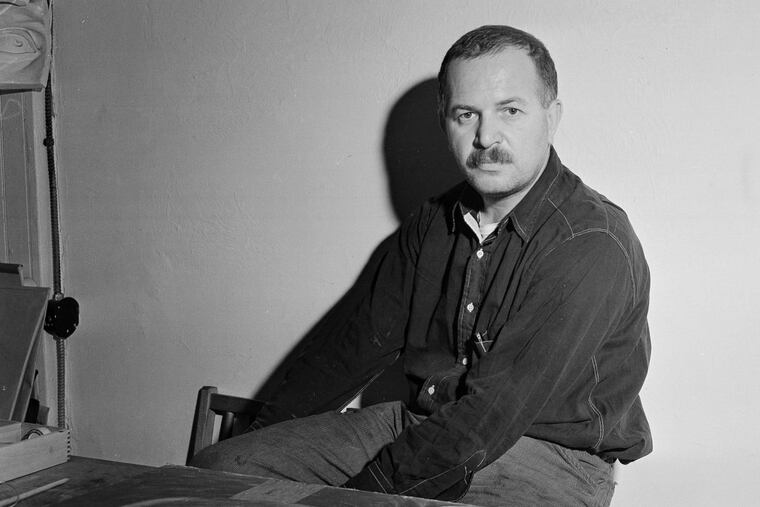

Whatever the reason, during Christmas break 1967, I visited the Philadelphia Museum of Art's exhibition on Ben Shahn.

Shahn was still alive and much of his work dealt with progressive causes — civil rights, the Sacco and Vanzetti case, organized labor. But not surprisingly, the one I recall best concerned baseball.

National Pastime is an ink sketch of a sweep of baseball action. A righthanded hitter takes a healthy cut. A crouched catcher awaits the ball. An umpire leans in close. A dark cloud of motion partially obscures them all.

At 18, as ignorant of art as life, I liked Shahn's drawing even if I couldn't explain why. What I did know, even then, was that it was no danger to anyone's freedom.

If you want to learn why NFL players kneel during the anthem or why the Eagles' forthcoming White House visit is so controversial, it helps to understand the episode when Shahn's innocent drawing ignited a 1950s culture war.

In its early years, Sports Illustrated's mission was far broader than now. The magazine ran stories on dog shows, bridge, and trout fishing. And deep in the Dec. 5, 1955, issue, with fencer Louise Dyer on its cover, was an article, "Artists and Sports."

SI, it noted, was partnering with the American Federation of Arts and the U.S. Information Agency to sponsor an exhibit of sports-related paintings, prints, and drawings. "A Happy Blending of Two Worlds," the headline said.

"Sport in Art" would include 102 "top-rank works." It would tour several American cities that summer and then, in September, travel to Melbourne for the 1956 Summer Olympics.

The exhibition seemed harmless. It linked sports and art, two disparate aspects of an ideal America that the 1950s would soon come to represent. But other forces were at work in that decade too, and they were busy banishing this nation's better angels to limbo.

Anti-communism was raging. "Reds" – even individuals whose greatest crime was an association with some progressive cause — were hunted in colleges, labor unions, the movies.

The House Un-American Activities Committee and other practitioners of McCarthyism, buoyed by many of the Americans they'd been frightening since 1946, made frequent demands. And, to a surprising extent, sports and society met them.

The national anthem, which some teams played before World War II-era games, suddenly became mandatory. The words "under God" were inserted into the Pledge of Allegiance and onto currency. The paranoia was so thick that in 1953 the Cincinnati Reds became the Redlegs, a change apparently made to aid those who confused third basemen and fifth columnists.

"Sport in Art" was well-received in Boston and Washington. But when in February 1956 it reached conservative Dallas, the same civic and business leaders who later accused President Kennedy of treason saw red and, of course, reds.

Four artists whose works were included — Leon Kroll, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, William Zorach, and Shahn –were labeled "Reds" by the ominously named Communism in Art Committee of the Dallas County Patriotic Council.

While all four leaned left, the artworks in question were hardly manifestos. What was more American than sports? Shahn had depicted a familiar baseball scene; Kroll and Kuniyoshi, skaters; Zorach, a swimmer.

But citing several reasons, council members insisted that either the art show be canceled or the artists banished. (A year later, the council managed to remove two Picassos from a Dallas library.)

One objected to "tax money going into the pockets of artists devoted to the destruction of our way of life." Another blamed Time Inc., SI's corporate parent, which he said was never mistaken for "an anti-communist publication." And a third claimed the exhibition enhanced the art's value "and thus gives money to the communist coffers."

After weeks of nasty sniping, more reasonable voices in Dallas and the art world prevailed. The exhibit took place.

It seemed President Eisenhower's defense of modern art was being heeded.

"As long as our artists are free to create with sincerity and conviction," Eisenhower said, "there will be healthy controversy and progress in art. How different it is in tyranny."

But before "Sport in Art" could be transported to Australia, the USIA, increasingly pressured by congressional hard-liners, pulled the plug.

National and international critics derided the decision as censorship. Meanwhile, many in Washington defended it, particularly Rep. George Dondero, a Michigan Republican who despised modern art as much as he did Lenin.

"Abstractionism," he said in one typically obtuse tirade, "aims to destroy by the creation of brainstorms."

Shahn, who died in 1969, and his drawing had been a focus of the dispute, probably because baseball, like religion, was seen as a bulwark against communism. When the Bolsheviks conquer us, the thinking went, they're coming for our Louisville Sluggers

According to a 2010 book on that subject, The Empire Strikes Back, the cast of TV's Father Knows Best was recruited for a Treasury Department film on what America might look like after a Soviet takeover. In it, the family's teenage son was prevented from playing baseball, his bat and glove confiscated.

All these years later, the American way of life and baseball survive. And if you're ever inclined to visit a place that epitomizes both, get to the ethereal Field of Dreams amid the cornfields in Dyersville, Iowa.

And while you're in the Hawkeye state, plan a side trip to the Des Moines Art Center. Hanging there on a wall, in the heart of America's heartland, is Shahn's National Pastime.