An appreciation: Darren Daulton gave us everything he had

Darren Daulton's contributions to the Phillies' 1993 National League pennant could not be measured simply by numbers, although they were also incredibly good.

A vivid image came to mind immediately after hearing the news late Sunday that Darren Daulton's four-year battle with brain cancer was over and he was dead at age 55. In the flashback to 1993, an exhausted Daulton was seated on the floor in a small room with his back to the wall and a beer in his hand.

Two Toronto players — one of them was closer Duane Ward, the primary reason the Blue Jays had just won their second straight World Series — had come to the visiting clubhouse to congratulate the Phillies for putting up such a dogged fight before falling in six games. Daulton looked simultaneously saddened by defeat and satisfied with the effort. He had every right to feel that way.

Daulton had given the Phillies everything that season. He had contributed so much more than 24 home runs, 105 RBIs and 117 walks, although those numbers alone would have been enough. Consider this: The 117 walks were more than any of the eight catchers in the Hall of Fame ever had in a single season. But no statistic could begin to explain how much "Dutch" meant to the 1993 Phillies.

That night in Toronto was not the first time I had seen Daulton exhausted. Game-time temperature on July 7 at Veterans Stadium that season was 94 degrees. The on-field temperature was 147 degrees. Remember how the heat from the Vet's turf hovered visibly in the air? The Phillies and Los Angeles Dodgers played 20 innings and more than six hours that night, finishing after 2 a.m. Daulton caught every inning, and this was only five days after the Phillies had played a doubleheader with the San Diego Padres that lasted until 4:40 a.m.

"It has been a long week," Daulton said after the 20-inning game. "I think it has been a week, anyway. One thing I know is that it won't be this hot all season. It can't be. We'll all die."

Daulton and the Phillies survived that summer heat wave and captured the hearts and minds of the city that season. If it's true that it is really about the journey and not the destination, then it is impossible to feel any better about a team than Philadelphia did about that one. And, to a man, the players from that season will tell you the primary reason it worked was that Daulton was the glue.

He policed the clubhouse, played the role of media spokesman and handled the pitching staff, which also meant he had to counsel Mitch Williams through a lot of nervous ninth innings. The late John Vukovich, the bench coach for the 1993 team, summed up Daulton's contributions best.

"I played with better players and I've coached better players," Vukovich said. "But in 32 years, I never saw a bigger leader. For me, he set the standard of being a man."

Daulton, of course, also set the standard for being the most handsome of men in the eyes of a lot of women. When his first child, Zach, was born in the early 1990s, former Phillies pitcher Jason Grimsley looked at the kid and confidently predicted "that kid has zero percent chance of being ugly." It helped that the first Mrs. Daulton — Lynne Austin — was a Playboy Playmate and the original Hooters model, but the well-tanned catcher from Arkansas City, Kan., contributed his share to the kid's blessed gene pool.

It was the beautiful person, however, that made me fall in love with Darren Daulton. I liked him a lot when I covered him from August 1988 through July 1997. In the beginning, it looked as if he might be gone almost before my tenure as a baseball writer started. The Phillies contemplated keeping Tom Nieto and Steve Lake as their catchers out of spring training in 1989 and general manager Lee Thomas tried to sign Tony Pena as a free agent and trade for Sandy Alomar Jr. in the winter of 1990.

Daulton persevered because that is what he always did. Nine knee surgeries could not stop him from playing baseball, and even when he could no longer catch, the Marlins wanted him as their team leader as they fought for a wild-card playoff berth in 1997. He immediately assumed that role in Miami and finished his playing career with a World Series victory.

"I went through a lot of wars in Philly, and I'll always respect that," he said after the Marlins had beaten the Cleveland Indians. "But coming over here couldn't have worked out better. This has just been wonderful. I'm not even sure I know how to describe how good this feels."

What a way to end a career.

Life after baseball was not always kind to Daulton. I'll never forget the dazed disappointment in his voice when I called him to talk about the Phillies' decision to hire Larry Bowa as the team's manager after the 2000 season. Daulton was the runner-up for the job, even though he had no professional coaching or managerial experience. He was considered because Ed Wade, the general manager at the time, knew firsthand what kind of leader he had been in 1993.

Daulton also struggled with alcohol and legal issues after his career, including spousal-abuse charges that eventually led to a 2 1/2-month prison term when he did not abide by a legal agreement as part of his divorce from his second wife, Nicole.

When Daulton wasn't making legal news, he was the subject of ridicule for his belief in the supernatural that he shared in the book If They Only Knew, which was released in 2007. People thought he was crazy and maybe he was a little, but he never stopped being kind to others or accountable for his actions.

Here's what he said at the end of an interview with Philadelphia magazine in 2010: "Anything I did in the past is my fault. Not my ex-wife's fault, not any of my kids' faults, not baseball, not the media — me, my fault. I did the damage. Will you make sure that comes through? Will you do that for me?"

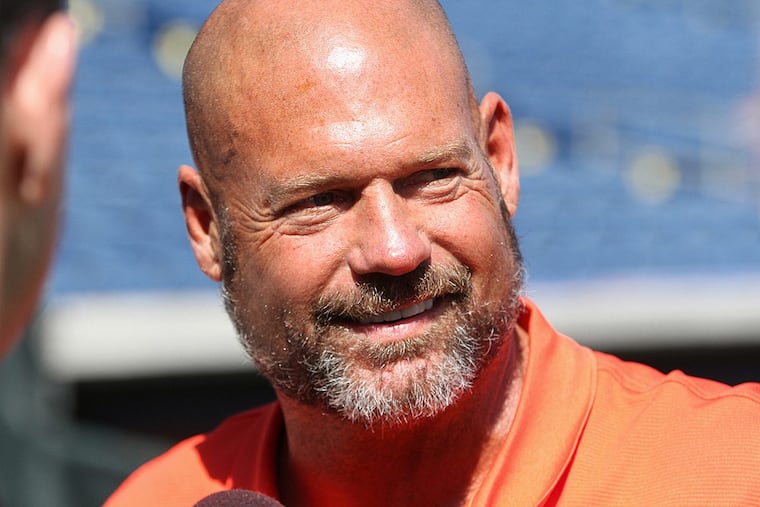

I saw Daulton a few times after he was diagnosed with two brain tumors in 2013. Two years ago, he made a spring-training appearance in Clearwater after announcing on Twitter that he had a clean bill of health from his doctors. You knew from experience — Vukovich, Tug McGraw — that brain cancer was relentless, but Daulton's smile and presence at the ballpark that day made everybody feel good. The Phillies tried to encourage him to put on a uniform and help with some coaching duties as he had in the past. He was content with coaching other cancer patients through difficult times as part of his work with the Darren Daulton Foundation.

The last time I saw Daulton was a year ago. He was with his wife, Amanda, at the Phillies' alumni weekend, an event he embraced with the same passion he played. We hugged and he said he wished we could go out for a beer with Lenny Dykstra. I don't know how soon after that Daulton's health took a turn for the worse. I do, however, have this vision of an exhausted Darren Daulton sitting on the floor with a beer in his hand. He is saddened that he has left us too soon, but satisfied he has given us all he had.