Sixers' storied stats crew has counted it all, from Wilt Chamberlain to Joel Embiid

With roots that go back to Wilt Chamberlain's 100 point game, the Sixers stats crew started by Harvey Pollack, run for decades now by his son Ron Pollack, has seen it all.

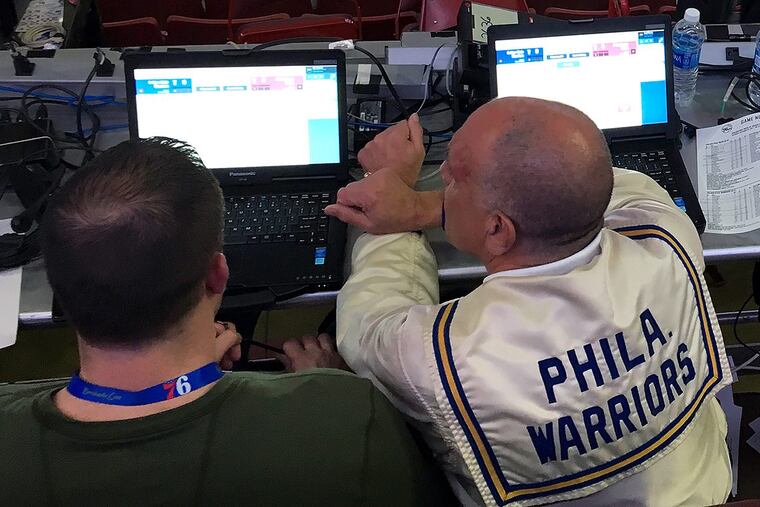

About an hour before the 76ers tipped off against the Golden State Warriors, Sixers television play-by-play man Marc Zumoff took a look at Sixers statistical ace Ron Pollack passing by above the Wells Fargo Center court.

"Like the jacket," Zumoff said.

"It's probably been washed three times," Pollack told Zumoff.

Since 1954 or '55, Pollack meant, since that's when this warm-up jacket saw the court, he said, worn by a Philadelphia Warriors player back in the Convention Hall days. Not the embellishing type, Pollack isn't sure which player wore it — "had to be a guard," Pollack said. The jacket had a flap on the back that read PHILA WARRIORS. The perfect evening to bring it out.

Understand that if there's local basketball history to be made, Pollack's crew is around to record it. Pollack's late father, Harvey Pollack, basically invented the stat-counting business in the NBA and his son has been right there for so much of the history, including when Wilt Chamberlain scored 100 points in 1962.

This night, Scott Berman, whose own late father ran the shot clock at Sixers game for five decades, was the crew's "caller,'' a play-by-play announcer but for a most exclusive audience, the other members of the crew stationed around the building with headsets. Berman sat next to Pollack, just to the left of Zumoff and the television crew, at the top of Section 112.

"Basically calling the action as it happens, with every detail — missed shot, made shot, assist, steal, offensive rebound, defensive rebound," Berman said. "In code."

The code is meant to be cracked, with player's numbers and what they just accomplished or failed to accomplish, as descriptive as possible. Not just a jumper, a turnaround or fadeaway. It comes out rat-a-tat so nobody falls behind the action continuing on the court.

That time Wilt scored his 100, Ron Pollack, then a sophomore at Northeast High, sat next to his father, who died in 2015 at age 93. Ron's job for that Wilt 100 game was to keep a running play-by-play sheet while his father tallied all the statistics. Ron began getting paid for his counting in 1960, has been there ever since. "It's a great diversion," said Pollack, for decades a computer consultant during daylight hours.

The recent Warriors-Sixers game was another one from statistical heaven, with the Sixers putting up 47 points in the first quarter, the Warriors storming past with 47 of their own in the third. For the crew, however, there was no time to pause to ponder any of that. "I'll look up and say, 'Hey, we're up 10 or down t10,' " Pollack said. "You're seeing the plays but you're not getting the whole picture of what's happening.' "

The Pollack legacy

Pollack, 71, has been in charge of the crew since 1982, now keeping a spreadsheet with 37 names across the top, all the people who keep stats for him at local college and pro events. This day, the crew also handled the Temple-UCF football game at the Linc, which meant Pollack had to walk only across the street to get to his nighttime assignment. Variations of the crew — also known as "the syndicate" back when Harvey Pollack was in charge — also handled men's and women's games at St. Joseph's, Penn, Drexel, and Rider, and Villanova's football game against Delaware. Between the beginning of September and the end of December, the crew would be responsible for compiling statistics at 122 games. Pollack himself would get to 28 games. (The crew leader in that time, George Burbage, had 45 games).

"We have to remember where we are," Pollack said.

He meant more than just in a geographical sense. NBA rules differ from those of college ball, and so do the rules for counting.

"The pass is supposed to create the opportunity for the shot, as opposed to just throwing the ball to the guy," Pollack said of NBA guidelines. And even the definition of a shot differs, with college ball holding the harder line. The NCAA says a shot attempt has to leave a shooter's hands, while the NBA begins a shot attempt at the beginning of the shooting motion.

Now there's also a Big Brother watching NBA games from league headquarters, with someone in Secaucus, N.J., monitoring the statistics gathered in real time, with the ability to instantly change them.

One aspect hasn't changed. The official book still is kept courtside by the official scorer wearing a referee's striped shirt. At Sixers games, that's Mike Sullivan, only the third to have the role in half a century. The stats that officially count are the ones in his book. He got his start on the crew when he worked in the sports information office at St. Joseph's. His book is easily legible, keeping shots made, timeouts taken, personal fouls accumulated, etc. Sullivan keeps the first quarter in a blue pen, switching to red, green, and black for subsequent quarters.

This night, the league's new computer system froze a couple of times, including in the opening minutes, which was a nightmare for the crew — "There's so much going on it's hard to catch up," Pollack said. It's far different from the era when one person would keep the entire box score at a Penn game. (These days, college games need three crew members.)

These are precise people, so when you ask them before the Warriors game whether Harvey Pollack invented certain statistics, they'll tell you, no, it wasn't as if Harvey invented categories of stats, he was just the guy who began counting so many of them. When Pollack was a Temple men's basketball manager in the early 1940s, he asked Owls coach Josh Cody if he'd be interested in offensive and defensive rebounds. Counting turnovers? Why not. From hockey, Pollack stole the plus-minus system for figuring out the score while a player was on the court. For Larry Brown, Pollack also added plus-minus numbers for each grouping of players.

Players keep score, too

Did players pay attention? What do you think?

"Wilt always knew how many rebounds he had," Ron Pollack said. "If you had him for 32, he'd tell you, 'I had 34.' "

There are occasional player complaints. Brian Pollack, Ron's son, who began in the family business putting Charles Barkley rebounds on a public board at the Spectrum as a teenager — Barkley B's — remembers Allen Iverson coming by just one time with a turnover complaint — "It's not my fault these [expletives] can't catch it."

In the old days, the game would end and the players and stat crew would all end up at Pagano's in West Philly for chicken and refreshment. Even if contact with players is reduced these days, some guys still make an effort. Like the time Joel Embiid wanted to meet the guys who kept the stats.

"Help me," Embiid quipped to Pollack.

"I'll try not to count too many turnovers," Pollack quipped back.

"Now with the security it's like the president is in town every game," Pollack said, remembering the days when the entire front office was maybe five people, including his father, the PR director. "There was no secretary," Pollack said. "My father did his own typing."

Pollack will tell you how Brett Brown stopped at the hospital when his father was in his last days.

"He came twice, and spent I'd say an hour with me, by himself," Pollack said. "My father didn't know he was there. He just talked to me about everything, his family and my family."

Given how Harvey Pollack was so far ahead of his statistical time and influenced those who came later, Sullivan walked around the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and could find only one mention of Harvey, on a list of awardees of a lifetime achievement award, which Pollack received in 2002.

"But he's not in the Hall of Fame," Sullivan said. He asked for an employee, asked if there was a Pollack display anywhere that he was missing. There was not.

All these Sixers wins and losses and players and coaches and ownership changes later, a constant is the group counting it all up. Berman, who figures he is second now in crew longevity, remembers how he fell in love with basketball statistics as a child. His father would bring him to games and he gravitated to the stat man. He'd keep his own scorebook. Harvey Pollack would grade the 12-year-old on his stats. No evaluating on a curve either. "He was tough," Berman said.

In this line of work, this crew will tell you, the facts need to stand on their own.