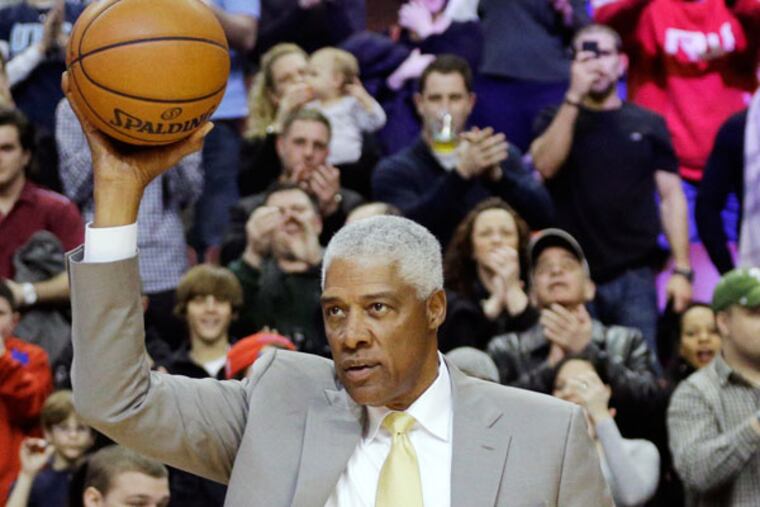

Doctor J's life an open book

Former Sixer Julius Erving writes an excruciatingly honest autobiography.

DOCTOR J took the playground game indoors. Took it to a higher level. Above the rim. Flew like a condor, stung like a scorpion. Found wealth and fame in that thin air. It was different at ground level, both feet on the shifting terrain. All that gloom. All those people he loved, dying young.

He has written his autobiography, with considerable help from Karl Taro Greenfeld. Calls it "Dr. J" when it could have easily been called "Julius Erving." Slice it and balance the parts, sadness outweighs joy 60-40.

When he played he was a knight in glistening armor. Elegant, graceful, kind. Nobody knocked Doctor J. Until now.

Now, he wants the world to know he was a cheating husband; an overmatched, overindulgent father; a naive businessman. And, oh, yeah, as a player he chose greedily from the smorgasbord of arrogantly perceived entitlement, grabbing fistfuls of available women from column A, while spurning column B, equally available drugs and booze.

He's 21, playing in the ABA, he decides to experiment, to see if he can sleep with a different woman every night. For eight nights, he does it, scoring in Dallas, Richmond, Va., St. Petersburg, Fla., New York, Charlotte, Louisville, Ky., and then Hampton, Va. "A different fox every night," he brags, "an Asian woman, a sister, a Caucasian, and so forth. But after a few nights, the excitement and macho thrill wear off and I start to feel empty."

It's still 1,992 short of Wilt's braggadocious claim, but it might sell books. That and the smarmy description of his relationship with sportswriter Samantha Stevenson. Their hanky-panky predated Monica Lewinsky and Bill Clinton in the White House, but Erving boasts that the pattern was the same and that's saying a mouthful. Erving insists he had sex with that woman only once, when orthodontia work left her with a mouthful of ominous braces and wires.

Nine months later, he gets a letter notifying him of the birth of his daughter. His wife, Turquoise, is enraged and flails at him. Did he mention that he'd sometimes hit Turq, "but only in self-defense." When cooler heads prevail, they work out a financial agreement that calls for silence.

It is only when Alexandra Winfield Stevenson shocks the world, advancing to the semifinals at Wimbledon, that a sports writer outs Doctor J as the girl's dad. At that point you will put the book down and take a long shower.

There, we've got the ugly stuff out of the way. But when you yank your own knightly image off a pedestal, beware of falling armor and graffiti artists.

Basketball? There's plenty of basketball in the book. No lists! No toughest defender, worst coach, best teammate. Just some passing references that might stir debate and sell some books.

Bill Russell? "He went on to become, in my opinion, the best all-around player in the history of basketball."

Pete Maravich? "Pete Maravich is the most skilled basketball player I've ever seen."

Kevin Loughery? "He's the most intuitive coach I've ever played for."

You've got to slog through 301 pages before the Sixers grab Erving from a bankrupt Nets' team, change his number to 6, as in $6 million. He modifies his flamboyant game to fit in with George McGinnis' ego and Gene Shue's hefty playbook, which Erving scorns.

They blow a 2-0 lead against Portland with a ludicrous scuffle between Darryl Dawkins and Maurice Lucas low-lighting the second game. An angry Dawkins destroys the clubhouse plumbing.

"I'm thinking," Erving writes, "we're supposed to back up Dawk? Chocolate Thunder? He's 6-foot-10 and 260 pounds. He is our enforcer."

The Trail Blazers win the next three. Game 6, Erving scores 40 but misses the potential game-tying shot. Shue then calls a play for McGinnis. "I think," Erving writes, "we should run a play for Doug Collins or let me drive. But I don't say anything . . . George misses the final shot." Game, set, match.

McGinnis was mired in a shooting slump. Somehow Erving omits describing a practice session in Portland where every time McGinnis missed a shot, his teammates chanted, "Brick!" In the handbook on slump-busting, is that an option?

There's the heartache against Boston, accurately depicted, squandering a 3-1 lead.

There's the triple heartache against the Nets, without reference to Erving saying they could "mail it in." And there's the tawdry scuffle with Larry Bird, hands around his throat.

Is it an urban myth that Bird, a Hall of Fame trash-talker, had just told Doctor J that if he kept guarding him, he'd get 50? We don't get the answer here.

What we do get is sorrow. Erving's sickly younger brother Marky dies of complications from lupus at 16. "It's out of order," Erving wails. He loved Marky deeply, felt guilty that he could run so fast and jump so high while impaired lungs kept his kid brother from doing the same things.

And then his sister, Freda, dies too young of cancer.

The crusher was the tragic death of his son Cory. Went off on a "bread run" the night of a dinner party. Vanished. Was finally found, in his car, in a pond, having taken a shortcut home from the bakery.

Warts-and-all biographies are plentiful. But this many blemishes in an autobiography by someone we all regarded as noble?

Erving gives us a clue in the fly-leaf.

"I want to be candid about my life," Erving writes. "I want to recall with you everything that I have seen and done, and try to make sense of this ongoing journey. While it has not always been easy, it has been exciting and, I believe, emblematic of our time."

The ball is in your court.