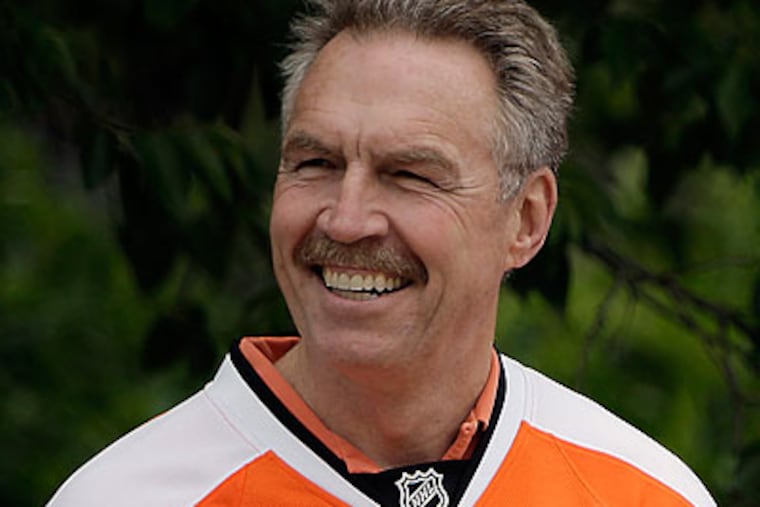

Flyer-turned-TV analyst Bill Clement shares his insights about leadership

Freddie Shero pulled out a piece of string one day and taught them all about leadership. You pull on the string and it follows you anywhere. You push on that limp string and it goes nowhere. Bill Clement watched Bobby Clarke pull guys to back-to-back Stanley Cup championships. When time was short and the stakes high, Clarke could push, too, staccato phrases, sharp as a cattle-prod, delivered where the sun don’t shine.

Freddie Shero pulled out a piece of string one day and taught them all about leadership. You pull on the string and it follows you anywhere. You push on that limp string and it goes nowhere.

Bill Clement watched Bobby Clarke pull guys to back-to-back Stanley Cup championships. When time was short and the stakes high, Clarke could push, too, staccato phrases, sharp as a cattle-prod, delivered where the sun don't shine.

And now, Clement has written a book called "Everyday Leadership" about those Flyers teams, about his triumphs and tragedies, about walking the tightrope over a canyon littered with fears and anxieties.

"Bobby's leadership style was his greatest asset," Clement recalled. "Besides his desire to work until his heart burst. He had that willingness to have the tough conversation, the one that is hard for most people.

"He chose his delivery style depending on the circumstances. He came to me, I could hardly walk, let alone skate, during the finals against Boston. I wound up playing games 4, 5, 6. Because Bobby made me feel vital to the outcome."

That was the gentle pull, the healing smoke, the tender side of leadership. Rick MacLeish felt the red-hot poker, Game 5.

"MacLeish came off from his shift and sat down beside me to my left," Clement writes. "Bobby was to my right. Rick was our most talented and skilled player but his motor didn't always run at high speeds.

"Bobby let Rick catch his breath for a few seconds, then leaned in front of me with his jaw clenched and in a level but stern voice said, 'Ricky? I sure hope you're saving it for game six, you son-of-a-bitch!' And then sat back, upright."

Clement played with finesse. He seldom fought. The team was known as the Broad Street Bullies, and they led the league in penalty minutes both years they won the Cup.

"I delivered gloves to the penalty box," he jokes. "I was the glove delivery boy. I realized, without that [Bullies] identity, I wouldn't have two Stanley Cup rings.

"It wasn't my identity, it wasn't Terry Crisp's identity, it wasn't Simon Nolet's identity. I didn't see Billy Barber drop the gloves that often. We all had our roles, plus the universal image based on six to 10 really tough guys.

"People say we won because we brawled. We were talented, we were driven, we sacrificed for one another, we all subordinated our individual interests for the good of the team. Not one guy made it about himself. It was always about us."

Clement scored the last goal of that second championship season and was gone before the Cup was drained of champagne. Traded. They walk together forever and, yes, Clement is right there with them.

"There was a sense of loss, an emptiness, a loneliness I felt when I was traded," he says. "It created a void, it was hard. They still had one another. I was gone. For months I felt as if marooned on an emotional island, that closeness I had felt was gone."

There were bleak stops in Washington, in Atlanta. Clement was prepared for life after hockey. He is always prepared. But that first restaurant venture splattered into bankruptcy. Two marriages failed.

Acting preceded a return to hockey as a television analyst. Meanwhile, his career as a motivational speaker blossomed.

"For years," Clement recalls sadly, "I was deathly afraid of public speaking. My first real gig, I was 21, with the Flyers, and [agent] Mark Stewart called, said I'd get 100 bucks, a little father-son Q-andA. It turned out to be at Father Judge, maybe the largest private school in the state.

"Tom Woodeshick, the Eagles runner, spoke first. They laughed, they cried, they applauded. I had nothing prepared. I go up there, the room got cloudy, I almost passed out.

"I didn't want it to end that way. I wanted to get back on that tightrope and walk across the gorge. To this day I get an adrenaline rush and a knot in my stomach as big as a basketball before I speak.

"So it takes some courage to get up there. And I tell the people that there are fears and anxieties in the canyon. But I want them to understand that the canyon floor is not lethal. You fall, you dust yourself off, you pinch and claw your way back up.

"The world doesn't care how many times you get knocked down. It's how many times you get back up."

The Flyers' season is over. Clement reluctantly takes part in the inevitable autopsy. People want to know what happened to Claude Giroux, the hero of that game against the Penguins, knocking Sid Crosby on his ascot, scoring that early goal. Wound up watching that final loss to the Devils in a suit, suspended for a cheap, angry hit on Dainius Zubrus, furious about an infraction that wasn't called against the Devils.

"That first shift against Pittsburgh," Clement explained, "Giroux was in control of his emotions. That hit against Zubrus, his emotions were controlling him.

"It's a perfect example of how our behavior can end up being something negative if you allow your emotions to control you. This can be a great leap forward for Giroux. He knows this. Wow, it hit him right in the head."

Contact Stan Hochman at stanrhoch@comcast.net.