Earmarks are back. Here’s what lawmakers want Congress to spend money on in Pa. and South Jersey

From urban to suburban to rural Pennsylvania, the spending requests from members of Congress read like an X-ray of gaps in the social safety net and differences in opportunity across the state.

WASHINGTON — Earmarks are back.

If lawmakers have their way, Congress may soon set aside $1 million for a sports and recreation facility in North Philadelphia and $500,000 to help people with mental health problems or addiction avoid incarceration in Bucks County. There’d be $5.5 million for a new police and fire facility near Scranton, $1.5 million to restore the Lansdowne Theater in Delaware County and spur economic development, and $1 million for a building to house a new nursing program at Lebanon Valley College outside Harrisburg.

Those are just some of about 170 spending requests submitted by House Democrats and Republicans from Pennsylvania and South Jersey. They seek aid for job training, downtown streetscapes, school and municipal buildings, food banks, YMCA upgrades, rural broadband, and more.

The requests are all part of the return of “earmarks,” federal money set aside by individual lawmakers. Renamed “community project funding,” they’re back a decade after Republicans banned the practice following corruption scandals. House Democrats are allowing every member to request up to 10 items in spending bills.

Senators also get a chance, though Pat Toomey (R., Pa.) won’t participate, saying earmarks spend money “not based upon merit, but politics.”

Democrats who control the House say they’ll set aside 1% of discretionary spending for the requests, which would be about $14 billion under current spending levels. So lawmakers won’t get everything they want, and were told that only a couple asks each might be approved, said Rep. Mary Gay Scanlon (D., Pa.).

Pet projects? Or local knowledge?

Supporters say earmarks allow lawmakers to steer resources to organizations and projects they know firsthand, instead of leaving it to distant officials.

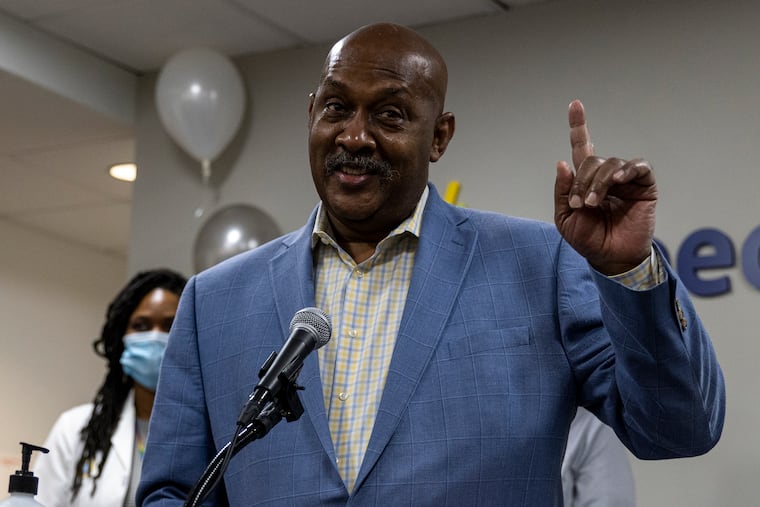

“Who’s closer to the constituents?” said Rep. Dwight Evans, a Philadelphia Democrat. “We’re on the ground.”

Evans has visited or volunteered with several of the 10 organizations he sought money for, including the nonprofit Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium ($1 million requested). Fellow Philadelphia Democratic Rep. Brendan Boyle asked for an additional $5 million for the group’s parent nonprofit, It Takes Philly.

Rep. Dan Meuser, a Northeastern Pennsylvania Republican considering a run for governor, emphasized the money would be spent regardless. If lawmakers didn’t choose, it would be distributed by federal agencies “based upon what they thought was best, not what the district told me was best,” said Meuser, of Luzerne County.

He said his 10 requests, totaling more than $20 million, could boost economic activity in postindustrial areas.

Lawmakers also said earmarks could grease the wheels for deal-making, since it’s easier to persuade people to vote for bills that have specific benefit for their districts.

» READ MORE: Biden’s first 100 days: Speak softly and deliver a big pitch

Critics warn earmarks open the door to excess — or outright corruption. Three of Pennsylvania’s nine Republican House members — Reps. Fred Keller, Scott Perry, and Lloyd Smucker — made no requests.

“Congress should be looking at ways to eliminate wasteful spending, not place additional burdens on taxpayers and future generations,” Keller said in a statement.

Democrats and Republicans who support earmarks said they’ve added new transparency to the process. All requests are posted online, for-profit recipients are barred, and lawmakers certify that they and their immediate family have no financial stake in the projects.

The 18 Pennsylvania and South Jersey lawmakers who made requests sought more than $207 million. Their total requests range from $332,000 by Rep. Andy Kim (D., N.J.) to $38.5 million by Rep. Jeff Van Drew (R., N.J.).

Individual items were as small as the $32,000 Kim requested to expand a program connecting police with mental health workers, to the $15.5 million Van Drew sought for dredging and beach restoration in Cape May County.

The biggest requests were for infrastructure like sewer and water projects, airport upgrades, and repairs to affordable housing.

A societal X-ray

The requests read like an X-ray of gaps in the social safety net.

Pennsylvania lawmakers in both parties sought millions for mental health services, treatment for drug addiction, and social workers to help police respond to people in crisis.

“Addiction and mental health issues, those were underfunded and a huge problem pre-pandemic” and got only worse, said Scanlon, of Delaware County.

In cities, there were requests to aid food banks, provide job training, and create recreational opportunities for young people and underserved communities.

Evans said he received 73 requests and narrowed those to 10 by focusing on poverty. There’s also $1 million apiece for the Mann Center for Performing Arts and the Nicetown Sports Court.

» READ MORE: What to watch as Pennsylvania loses a congressional seat: ‘The stakes are really high’

Lawmakers in rural and postindustrial areas sought money to create job opportunities in struggling regions. Rep. Glenn Thompson (R., Pa.) requested $1.5 million in Jefferson County to train people in meatpacking. Meuser’s requests include $2.6 million for an Alvernia University expansion that would include simulators to train students to use heavy equipment.

Many asked for water upgrades and sewer repairs, including $500,000 sought by Republican Rep. Guy Reschenthaler for a Southwestern Pennsylvania school district where water is currently “trucked in,” according to the application.

Others emphasized racial inequities. One of Scanlon’s requests, for example, cited “decades of racist municipal and corporate disinvestment” in Southwest Philadelphia in seeking $925,000 for a watershed education center and mussel hatchery on the Schuylkill.

“Well-funded business and well-funded organizations, they always have a seat at the table,” she said. “This is supposed to be about community projects.”

A Norcross family connection

The ban on requests that could financially boost family members didn’t stop Rep. Donald Norcross (D., N.J.) from seeking $500,000 for Cooper University Hospital, where his brother, Democratic power broker George Norcross III, is the board chairman.

It could be allowed: While George Norcross is in many ways the face of Cooper, he has “never received compensation of any type,” the hospital said. Donald Norcross’ office said it checked with the House ethics committee before making the request.

The money would support “an innovative program” that trains military personnel alongside civilian doctors, the congressman said in a statement. He also pointed to his requests for other groups addressing food insecurity, housing for veterans, and mental health services for people who survived childhood trauma.

Republicans are OK with some spending and infrastructure

Republicans say they’re the party of fiscal restraint, and many have attacked President Joe Biden’s $2 trillion infrastructure proposal as excessive. But several made large requests that read like Biden’s blueprint.

Van Drew wants $1.5 million to convert the Atlantic City jitney fleet to electric vehicles.

Rep. Mike Kelly (R., Pa.) wants $2 million to extend a runway at the Pittsburgh-Butler Municipal Airport and $5.5 million for paving at Erie International Airport. Thompson wants $5.5 million for John Murtha Johnstown-Cambria County Airport. They cite the economic ripple effects of such projects.

Meuser, who sought $1 million to study connecting Reading to Philadelphia by rail, said that there are real needs for infrastructure investment but that Biden’s proposal would spend too much and include too many ancillary ideas.

“It’s not difficult to spend a lot of money,” he said.

Now comes the push to ensure the projects get funded.

“Will we be trying to twist some arms?” Scanlon asked. “Absolutely, that’s part of the job.”