What Pa. elections officials are scared about heading into November

Misinformation, litigation, and potential certification delays. Pennsylvania election officials are preparing for the worst in November as the state takes center stage.

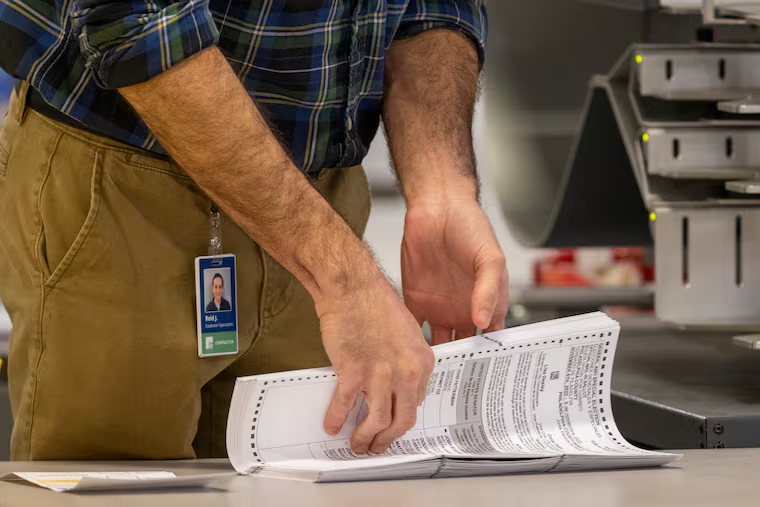

Elections officials across Pennsylvania are hopeful the 2024 presidential race won’t be a repeat of the chaos of 2020 — marked by a days-long wait for results, a deluge of misinformation, and baseless court challenges that dragged on for weeks.

But even as they say they’re better prepared this year to handle the problems from four years ago, many are bracing for another tight race that could breed new areas of confusion and uncertainty amid an intensifying culture of election denialism if the nation once again waits on Pennsylvania to know who the next president will be.

“The longer it takes to decide who the winner is, the more opportunity there is for unrest,” said Neil Makhija, chair of the Montgomery County Election Board.

Here are some of the scenarios that elections administrators, lawyers, and campaign officials fear most:

Misinformation and threats

If Pennsylvania election administrators learned anything from 2020, it was that delays in calling the election create fertile ground for misinformation to spread.

As Pennsylvania’s vote count that year stretched on for days, former president Donald Trump and others seized upon the moment to falsely suggest Joe Biden’s total had been padded with thousands of ballots overnight. (Those votes were the result of ongoing counting of mail ballots, which were heavily Democratic.)

Those conspiracy theories had only multiplied by that Saturday when projections called the state for Biden.

“In 2020 when that started … a lot of us thought it would end as each official action happened upholding the integrity of the election,” said Kathy Boockvar, the former Pennsylvania secretary of state who oversaw that election. “We all thought it would die down and instead it’s gotten worse over the last four years.”

Although misinformation and lies surrounding the 2020 election have grown, officials say that with more in-person voting and with several elections behind them in which they’ve hastened the pace of counting mail ballots, they’ll be able to report results sooner this year.

But, like in 2020, state law still prevents election officials from opening mail ballots until 7 a.m. on Election Day, making it likely that larger counties won’t finish their counts that same night. And mail ballots, counted later, may still skew toward Democrats.

Should the race prove as tight in Pennsylvania as some polls project, it could once again be days before it’s clear which candidate the commonwealth chose, allowing disinformation and even threats of violence to take hold.

“The window of time from when the polls close until when the race is called is still our biggest risk window for mis- and disinformation,” said Seth Bluestein, the lone Republican member of the Philadelphia City Commissioners, which oversees the city’s elections. “It’s really that misinformation that leads to harassment and threats.”

This year, misinformation is already swirling as Trump and his allies have repeatedly claimed without evidence that noncitizens will vote en masse.

In 2020, Bluestein’s predecessor on the commissioners’ board Al Schmidt — who is now Pennsylvania’s secretary of state — faced hostility and harassment after Trump singled him out on social media. And as the count dragged on, two Virginia men were arrested outside the Pennsylvania Convention Center, where the tallying was taking place, after arriving in a Hummer stocked with guns and emblazoned with QAnon conspiracy stickers.

Since then, elections officials across the country have reported continued threats, including Makhija who said he was targeted with suspicious mail after the RNC sued Montgomery County last month.

It’s a ubiquitous experience.

“There’s a general level of concern out there because I think everyone in the state who’s in election administration has had an experience of some kind going back to 2020, or maybe a year or two afterward that gave you pause,” said Forrest Lehman, the election director of Lycoming County. “Something that was concerning, or maybe even scary.”

But officials say they’re taking steps this year to prepare for any disruptions.

After 2020 Philadelphia’s commissioners moved their counting center to a permanent warehouse in Northeast Philadelphia, where they hope to avoid the same crowds that gathered outside their temporary 2020 headquarters in Center City.

Local and state enforcement organizations have announced task forces specifically designed to combat threats to election workers on or after Election Day. Gov. Josh Shapiro set up an election threat task force to help agencies coordinate.

Frivolous lawsuits

Even after Pennsylvania’s 2020 results were called, the Trump campaign and its allies contested them for weeks in court with a barrage of lawsuits — all of which were dismissed by judges with one panning the effort as “light on facts” and breathtaking in the presumptuousness of its request to set aside millions of votes in the state.

Officials were hopeful that the professional repercussions some lawyers involved in Trump’s effort have since faced — like Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani’s disbarment in Washington last month — would tamp down on similar filings this year.

But while the political parties have been engaging in legitimate, more routine legal disputes over which ballots should count under the state’s election code in the run-up to Nov. 5, the period has also seen a proliferation of organized legal challenges brought by right-wing “voter integrity” groups that critics have panned as thinly veiled attempts at voter suppression. The groups often have no direct tie to the Republican Party.

They stand little chance of succeeding in court, but experts say they can still sow needless doubt about the validity of the election results.

For example, the far-right group United Sovereign Americans sued Pennsylvania in June over flaws it claimed to have found in the state’s voter rolls — a strategy the group has deployed in other battleground states to suggest “confidence in the election [is] impossible.” The Pennsylvania Department of State referred to the suit as “a panoply of conspiracy.” That case remains pending in a federal court in Harrisburg.

Meanwhile, six Republican members of Congress — all of whom voted against certifying Pennsylvania’s 2020 election results — sued Pennsylvania in federal court last month, alleging its practices for verifying overseas ballots are susceptible to fraud. Election law experts have described their suit as a voter-suppression play.

“They’re trying to create a cloud of suspicion around votes that are totally properly counted,” said Pat Moore, a senior legal adviser with the Harris campaign, which intervened in the case on Friday.

Jim Allen, the Delaware County elections administrator, noted that his county has repeatedly been sued by the same people bringing discredited claims of malfeasance. Most recently, a federal judge tossed out a lawsuit that falsely claimed the county’s voting machines are not properly tested while seeking an order that would require the suburban county to shift to hand counting, a slow and less accurate method.

“It doesn’t matter if you show them all the envelopes and they come in, they photograph them. Two months later, they go into court and say, well we didn’t really see that many,” Allen said of local election deniers.

Campaign and elections officials say such suits still put strain on administrators, who must take time away from the counting of votes to deal with even the most frivolous filings.

“Am I worried that’s going to cost any qualified voter their opportunity to vote? Absolutely not,” Moore, from the Harris campaign said. “We’re 100% prepared for it. Is it going to be a needless burden on election officials … Yeah, and they deserve better than that.”

After the 2020 election several of Trump’s electors in Pennsylvania signed a document agreeing to be on an alternative slate of electors if any of the lawsuits overturned the state’s results. Five of those Republicans are back on Trump’s slate of electors this year. At least two of those electors said they would sign the document again if circumstances were similar this year.

Certification crisis

There’s one nightmare scenario that has worried state election officials for years, but so far has yet to materialize in a significant way in Pennsylvania: rogue county officials refusing to certify their vote totals over baseless, unproven allegations of fraud.

A report earlier this year from the nonprofit group Informing Democracy found across Pennsylvania 49 current county board of election members whose past behavior raised concerns about their commitment to certifying votes. This behavior included expressing skepticism about the 2020 election, calling for hand counts or audits, and voting against certifying any election since 2020.

In most cases, those members make up a minority of their election board and have not become serious roadblocks to their county approving its results. But in six counties across the state, (Berks, Fayette, Lancaster, Luzerne, Bradford, and Butler) they held a majority on the local elections boards.

And a compounding concern is that officials say the certification process — a normally routine, procedural step that under state law counties must complete within three weeks of Election Day — has come under more intense scrutiny from the public and election deniers.

“That pressure has really increased a lot and I just worry about what happens if you have some of these red, rural county folks refuse to certify their vote total because of some specious misty cloud of fraud claims people have raised,” said former Democratic U.S. Rep. Conor Lamb during a panel earlier this month.

Experts are already convening to contemplate worst-case scenarios. A group of national security experts and former military and civil leaders convened by the University of Pennsylvania evaluated what would happen if civil unrest at the polls compromised Pennsylvania’s elections. They warned leaders to prepare for the possibility of interference.

“Anyone who considers January 6 has to be aware of the potential for violence,” said Claire Finkelstein, faculty director at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Ethics and the Rule of Law. “And here we have a situation in which there’s been much more time to plan.”

A refusal or significant delay in a county’s certification could have a cascading effect. Federal law requires Gov. Josh Shapiro to certify the statewide results, allowing the state’s presidential electors to meet and cast its Electoral College votes, by Dec. 11.

Pennsylvania has never faced a certification crisis during a presidential race. All 67 counties certified their results on time in 2020.

During the 2022 primary, three counties — Berks, Fayette, and Lancaster — initially refused to certify, voicing objections to a court order and Department of State guidance to include undated mail ballots in their totals. State elections officials took them to court to secure a judicial order compelling them to certify their results.

But elections officials cite both examples as a sign that there are safeguards in place to ensure the process won’t be stalled by rogue actors.

Schmidt, the state’s top election official, said the Department of State would be prepared to take counties to court if needed.

In the end, said Schmidt, it’s not a matter of anticipating what could go wrong but being prepared for every possibility.

“All you can do is to make sure you’re prepared, and if none of that ugliness returns, all the better,” he said. “But if it does, we’ll be ready for it.”