Pennsylvania’s 2024 election results could be contested for weeks in court. Both sides say they’re ready for that fight.

Republicans and Democrats are engaged in an unprecedented push to recruit hundreds of lawyers across the state for what both sides are predicting will be a torrent of post-election litigation.

From county-by-county skirmishes over the validity of individual ballots to sweeping Republican-led challenges aimed at overturning the statewide results, the 2020 presidential race was the most thoroughly litigated election in Pennsylvania’s history.

But this year could end up giving it competition for that distinction.

Across the state, Republicans and Democrats are engaged in an unprecedented push to recruit hundreds of lawyers and volunteer observers in preparation for what both sides are predicting will be a torrent of postelection litigation.

And already, state courts have issued significant rulings that will dictate whether tens of thousands of contested votes are counted on Election Day.

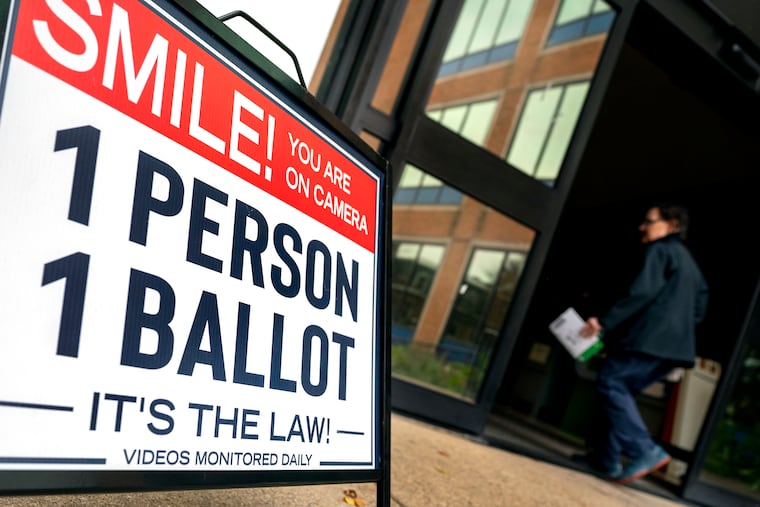

The parties maintain the ongoing legal arms race is about ensuring that all legally cast ballots — and only legally cast ballots — are counted in Pennsylvania. But the resources they’re pouring into that effort reflect what election lawyers describe as a new reality in the deeply divided state: Victory may no longer hinge just on who can turn out the most votes but also on who’s best prepared to defend — or attack — those votes in court.

“We’re in a new world now,” said Democratic campaign lawyer Adam Bonin, of Philadelphia. “Before 2020, the thought of any of this extending beyond Thanksgiving in all but the closest of races would have been completely unfathomable. Now, we know — in terms of the presidential race — it can go further.”

Broadly, lawyers on both sides say they’re hopeful that this year’s postelection litigation won’t be marked by the same outlandishness that characterized some of Donald Trump’s efforts to contest Pennsylvania’s 2020 election results in court.

That year, the former president’s campaign and its allies bombarded judges with dozens of legal challenges including, most notably, one led by attorney Rudy Giuliani that made sweeping allegations of widespread fraud but offered no evidence to back up those claims. Another, brought by Trump ally U.S. Rep. Mike Kelly (R., Butler), sought the exclusion of all 2.7 million mail ballots cast in the state.

» READ MORE: Trump and his allies tried to overturn Pennsylvania’s election results for two months. Here are the highlights.

Both efforts were roundly rejected by judges — including some Trump appointees. Some of the attorneys involved have since faced professional repercussions, including Giuliani, who was disbarred in Washington, D.C., in September over his involvement in the 2020 Pennsylvania litigation.

Because of that backlash, said Republican election lawyer Matt Haverstick, “I don’t think we’re going to see the same level of rancorous litigation this time around.”

But he and others predicted the volume of litigation could still equal — if not exceed — that seen four years ago.

Many of the legal fights to emerge so far have centered on more granular issues over which votes should count and increasingly they’re targeting smaller and smaller tranches of mail and provisional ballots, like those missing required dates on their outer envelopes or ballots cast at the polls by voters whose mail ballots have been previously rejected for procedural defects.

While rulings in those cases may affect fewer than 1% of the votes expected to be cast this year, the intensity of the legal fighting around them is indicative of the narrow margins by which the presidential race in Pennsylvania could be decided.

Consider that President Joe Biden eked out his 2020 victory over Trump by just over 80,000 votes. Polls suggest this year’s result could swing by even narrower margins.

“I would never predict turnout or who’s going to win or lose,” said Pennsylvania Secretary of State Al Schmidt, the commonwealth’s top elections official. “But it’s easy to predict the likelihood of litigation around presidential elections. … No one is going to be caught unprepared for any litigation that comes our way.”

A legal arms race

To that end, Republicans and Democrats have been working since earlier this year to line up their troops for the court battles to come — a push they described as their most robust election integrity efforts to date.

The goal on both sides? Placing lawyers and volunteers on the ground to monitor voting, canvassing, and certification in each of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties and to handle any issues that arise.

Democrats began their recruitment effort in mid-March and boast that they’ve recruited thousands of attorneys nationwide — nearly 10 times the number on hand in 2020. Kamala Harris’ advisers say they’re more prepared this year than they’ve ever been to combat what they characterize as Republican efforts to disqualify eligible votes in court, rather than winning over voters at the polls.

“For four years, Donald Trump and his MAGA allies have been scheming to sow distrust in our elections and undermine our democracy so they can cry foul when they lose,” Harris campaign manager Jen O’Malley Dillon said. “But also for four years, Democrats have been preparing for this moment, and we are ready for anything.”

The party’s legal efforts in court are being spearheaded by longtime Democratic election lawyer Clifford Levine, of Pittsburgh, who served as campaign counsel in the state to Biden in 2020. He’s backed by attorneys from around the state and a team from Washington-based law firm Wilmer, Cutler, Pickering, Hale and Dorr LLP that includes former Clinton-era Solicitor General Seth P. Waxman.

Republicans, in turn, have been represented so far by attorneys Kathleen Gallagher, of Pittsburgh, and Thomas W. King III, of Butler — both veterans of past GOP legal fights over mail voting — as well as by lawyers from the Washington-firm Jones Day.

Notably missing this year is Columbus-based firm Porter Wright Morris & Arthur LLP, which represented the Trump campaign in several early Pennsylvania legal challenges in 2020, only to withdraw that representation, under pressure from clients and staff, as unfounded claims of election fraud became more central to his arguments in court. The firm did not respond to requests for comment on its involvement in election-related work this year.

Meanwhile, the GOP has focused on lining up its own army of “election integrity” watchdogs — including lawyers and poll watchers — in hopes of deploying 100,000 across 15 states.

Dozens of prospective volunteers showed up at a recent Republican-led training event in Fort Washington, where party officials regaled attendees with pep talks that leaned on the party’s lingering suspicions of the 2020 results. Though reporters had been invited to attend the session, they were barred from the room once any actual training began.

“I’m confident that the legal team I have in place will be prepared to defend the voters in every county across the Commonwealth,” said Linda Kerns, the Republican National Committee’s election integrity counsel for Pennsylvania. “That is our goal: To protect the voters, to make sure that laws are followed, holding elections officials accountable and making sure that every legally cast ballot from an eligible voter is counted.”

The court battles to come

As for what they are likely to be fighting over, lawyers from both sides said the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s hesitancy so far this year to rule on several key issues before Nov. 5 could result in a proliferation of county-level court fights after Election Day.

In the weeks before the 2020 vote, the justices issued several opinions on matters ranging from the legality of ballot drop boxes and restrictions on poll watchers to the procedures for counting mail votes. That quick pace was, in part, driven by the fact that 2020 was the first presidential election in which Pennsylvania had offered no-excuse mail voting and courts were still defining the contours of the law that authorized it.

But this year — and several elections later — the justices have shown little appetite for considering last-minute, significant changes to the rules and procedures in place.

“This court will neither impose nor countenance substantial alterations to existing laws and procedures during the pendency of an ongoing election,” the justices wrote in an unsigned order Saturday refusing to hear an appeal brought by a coalition of voting rights groups challenging the current practice of rejecting mail ballots missing the required dates.

The same day, the court also refused to hear an RNC-backed case seeking to bar counties from alerting voters to procedural defects in their submitted mail ballots that could lead to their votes being rejected.

“I’m confounded,” said Witold “Vic” Walczak, legal director of the ACLU of Pennsylvania, which represented voting groups involved in both appeals. “When you have an issue that’s going to disenfranchise thousands of voters and [the courts] don’t decide this before the election, it’s going to come up afterward.”

To that end, the ACLU, along with other nonpartisan organizations, is working this year to expand efforts to monitor and challenge barriers to voting at the polls. They’ve lined up lawyers and volunteers in roughly 40 key counties prepared to handle issues in court as they arise, Walczak said.

“Part of the problem is we have an election code that has some gaps, and is not a model of clarity on every issue,” said Mimi McKenzie, legal director of the Philadelphia-based Public Interest Law Center, which is partnering in that effort.

Beyond Election Day, attorneys are preparing for legal challenges around the procedures for counting and certifying the vote.

Two years ago, supporters of then-Republican gubernatorial nominee Doug Mastriano flooded the courts with petitions to force hand recounts under a little-known provision of state law, even though Mastriano lost that race by more than 780,000 votes. Judges quickly swatted them away. The same year, however, the Commonwealth Court had to order three counties — Berks, Fayette, and Lancaster — to certify their vote totals after they held off on doing so amid disputes over which ballots should count.

Ultimately, Republicans and Democrats say they’re hopeful this election won’t require the same level of court intervention — but they are prepared for that possibility.

“The voters should have faith that they’re deciding elections — not judges and lawyers,” said Bonin, the Democratic campaign lawyer. “Let’s cut away all the nonsense, and see what the voters say.”