John Fetterman doesn’t just have supporters — he has fans. His celebrity could make him a senator.

In a midterm election year when Democrats are expected to struggle, Fetterman's outsized frame and unconventional political demeanor has brought him something of a cult following.

John Fetterman crossed his arms and cast his flushed face downward as the woman in a fedora started into her fourth verse of the song she wrote for him.

John, like Popeye, says, “I am what I am.”

On the side of truth, he’ll take a stand.

So vote for Big John in the Senate race.

He’ll make Pennsylvania a better place.

Pennsylvania’s lieutenant governor didn’t look particularly comfortable with the serenade last weekend in Bucks County (a parody of Jimmy Dean’s “Big Bad John”). But he graciously gave her an “I’m not worthy” bow as a room full of people, many in Fetterman campaign shirts, broke into applause.

As he closes in on the Democratic Senate nomination in Pennsylvania, Fetterman doesn’t have supporters so much as full-on fans. Fans who write songs about him, buy his merch, and know his life story. In a midterm election year when Democrats are expected to struggle, his outsized frame and unconventional political demeanor — plus the publicity that comes from three statewide campaigns and millions in TV ads — have brought him something of a cult following.

And while a quarter of Democratic voters remained undecided in a poll of the race last week, the 40% backing Fetterman don’t seem particularly inclined to change their minds. To the frustration of Fetterman’s opponents, he’s maintained his long-held lead even as they’ve ramped up their attacks.

“He’s direct and he’s consistent and he’s honest,” said Deb Freedman, a retired teacher who came to see Fetterman on Saturday in Yardley. “He’s the real deal and that’s what we love about him.”

At an American Legion Hall, about 100 Fetterman fans ate Wawa doughnuts and pretzels — a catering choice meant to playfully troll Fetterman’s loyalty to Sheetz, Wawa’s Western Pennsylvania convenience-store counterpart.

At 6-foot-8, Fetterman almost touched the drop ceiling with his bald head. He wore what’s become his campaign uniform: a Carhartt black hoodie and jeans. (The gym shorts he’s also known for came out later in Montgomery County, once the day warmed up.) For Fetterman, the casual way he dresses and presents himself — direct, unassuming, somewhat awkward — is as much a part of his pitch as his message of being an unabashed progressive who can also appeal to rural, disaffected Democrats.

Fetterman, 52, touted raising the minimum wage and ending the Senate filibuster. He promised never to compromise on Democratic values and drew laughs by poking fun at retiring Republican Sen. Pat Toomey’s “incredible talent” to be “hated so much by both parties.”

“If there is a terrible political price to pay for leaning in on any of those critical issues and values, I’ll take it,” Fetterman said. “If you’re not prepared to end your career to expand health care for everybody, increase the minimum wage, protect universal voting rights, then why are you in this business in the first place?”

Fetterman supporters can easily recite — often in the same language as his TV ads — nuggets about his life and career. They gush about his directness, his attitude, his “realness.”

And it’s not just the candidate. Fetterman fans are Fetterman family fans. When he walked into the Yardley event with his wife, Giselle — his fashion opposite in her bright pink dress and pumps — there were excited gasps from women in the crowd: “Giselle came!” The crowd that later formed around her was only slightly smaller than the one surrounding him.

A Twitter account for Levi, the family’s rescue dog, has 25,000 followers — more than eight times the following of Republican Senate candidate and actual human David McCormick.

“I’m obsessed with that stupid Twitter account,” said Donna Minton, 46, of Levittown. “Whoever runs that is just perfect.”

Minton was a Republican until 2018, when she soured on the party during Donald Trump’s presidency. She still has staunch Republican friends and family whom she thinks Fetterman could win over.

“They don’t hate him like they hate some Democrats,” she said. “They think he’s funny and he’s a man’s man. ... He’s real to them.”

Fetterman has made appealing to Republicans and more conservative Democrats a central part of his campaign.

“We’re not here because we have a plan to turn Franklin County blue,” Fetterman said last month in rural Chambersburg, near the Maryland border. “We’re here because we are going to need every last vote to make sure that we flip this seat blue.”

» READ MORE: John Fetterman still has a huge cash advantage in the Pa. Senate race, even after Conor Lamb’s best quarter

To the annoyance of his critics, who say the tough-guy package is more style than substance, Fetterman is Pennsylvania’s only real Democratic political celebrity right now.

“His presence is something that people remember,” said Neil Oxman, a longtime Philadelphia-based campaign consultant who’s unaligned in the primary. “He’s not phony. He doesn’t look like every other buttoned-down politician who wears a Brooks Brothers suit … and he’s made a million appearances on cable TV.”

“He’s become absolutely, unequivocally, a cult figure,” Oxman added.

Fetterman, who lives outside Pittsburgh in Braddock, had mostly campaigned in the western and central parts of Pennsylvania until last weekend. His crowd in Yardley — and in Plymouth Meeting later in the day — was almost entirely white.

He hasn’t done any large, public, in-person campaign events yet in Philadelphia, but his TV ads are on local airwaves plenty. A huge proportion of the state’s Democratic voters live in the region.

“He’s playing to his base,” Mustafa Rashed, a Democratic consultant who’s neutral in the primary, said of Fetterman’s focus farther from the city. “They’re there. They’re turning out. They seem immovable and they seem willing to go all the way with him.”

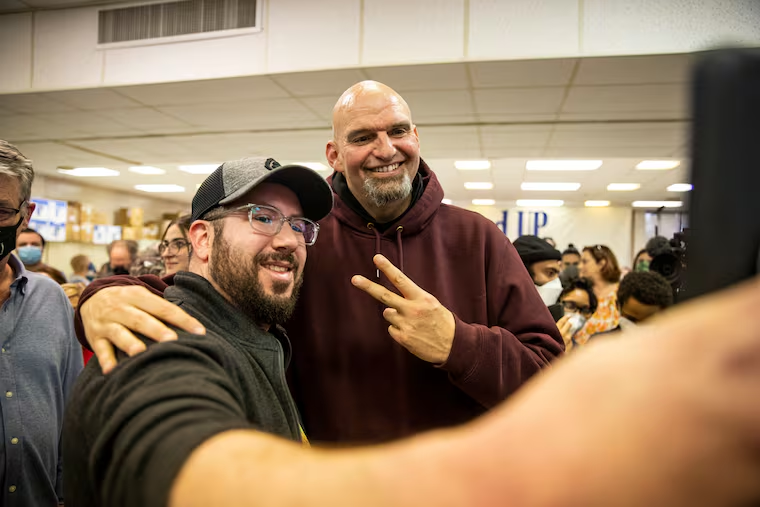

At UFCW Local 1776 in Plymouth Meeting, which represents commercial and food workers, Fetterman waded through a sea of selfies.

“You’re exactly who we need,” one woman said. “Take care of yourself, now,” a man told him. “Make sure you’re eating right.”

One voter said she was delaying a move to Mexico to vote for him. An engaged couple asked if he’d officiate their wedding. He raised a baby to the ceiling and a dozen iPhones followed.

Fetterman’s gym-shorts celebrity isn’t celebrated by everyone.

“It’s disrespectful for the office he’s running for,” said Ryan Boyer, head of the Philadelphia Building Trades, which supports U.S. Rep. Conor Lamb in the primary. “It sends the wrong signal for people that don’t have his level of privilege. I mean, could you imagine if Fetterman was a 6-foot-8 bald-headed big Black guy? Would he have that level of success?”

Others argue it’s just not authentic, given that Fetterman grew up wealthy and went to Harvard.

“It’s an obvious farce,” said Jake Sternberger, a Democratic consultant who ran Joe Sestak’s Senate primary campaign against Fetterman in 2016. “He’s a trust-fund rich kid who is cos-playing as a working-class poor person.” Sternberger said the frustration is magnified “when you have in the race a candidate like [State Rep.] Malcolm Kenyatta, who grew up very poor.”

» READ MORE: Malcolm Kenyatta is tired of being told a Black gay man from North Philly can’t win Pa.

In Plymouth Meeting, Fetterman focused on his family’s more humble beginnings. His father, who became a successful insurance executive and donated heavily to his son’s campaigns, started as a union worker stocking shelves at ShopRite.

“I was born to two teenage parents. And let’s just say I wasn’t part of the plan when they were dating,” Fetterman said. “Fifty-two years ago, your union was there for our family. And now it’s an honor of a lifetime to be there for yours.”

For some Fetterman fans, it’s all part of his appeal.

“The man looks like a football player and he’s as smart as a Harvard graduate,” said Michael Barkan, of Yardley. “He’s a nice guy, but he could be intimidating if he needs to be, and I think we need something like that in Washington.”

Staff writer Jonathan Tamari contributed to this article.