Inflation is still voters’ top concern. We took a look at what Fetterman and Oz say they would do.

Inflation and the economy consistently rank as the top priorities for voters, and have weighed on Democrats. Here's what experts say a new senator could do about inflation.

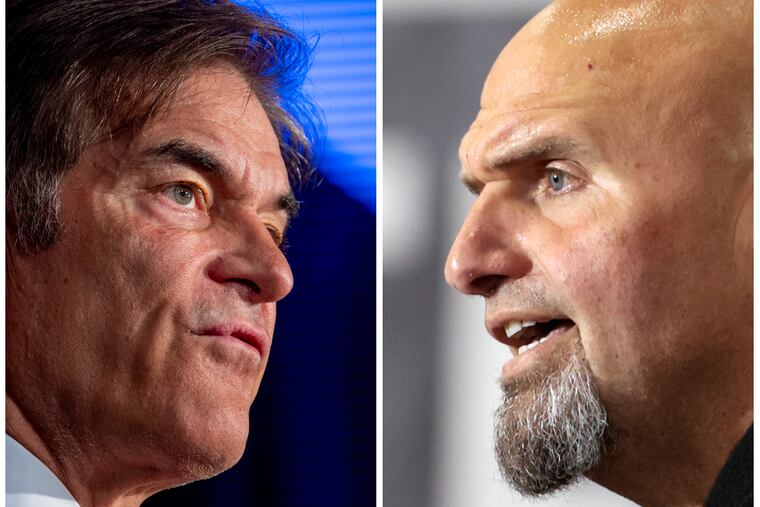

For months, Pennsylvania’s Senate race has been dominated by abortion rights, crime, Mehmet Oz’s New Jersey ties, John Fetterman’s health, and Twitter trolling.

But inflation is the issue that started atop voters’ minds — and it remains there.

The most recent economic data, released last week, showed prices rose by 8.2% in September compared with the previous year, the latest sign that inflation is still straining household budgets. It’s an issue people routinely experience firsthand, in stark numbers at the bottom of their receipts.

Some 87% of Pennsylvania voters see jobs, the economy, and the cost of living as extremely or very important to them this election, according to a Monmouth University poll released in early October, the largest share of any issue. And polls suggest it’s weighing on Democrats nationally.

Both Fetterman, the Democratic nominee for U.S. Senate, and Oz, the Republican candidate, have talked about fighting rising prices. But how much influence could any senator really have?

Not much, according to economists.

“In terms of things that would lower prices on store shelves, it’s pretty tough to act that quickly,” said Josh Bivens, director of research at the liberal Economic Policy Institute.

“They have delegated price stability to” the Federal Reserve, said Carola Binder, an associate professor of economics at Haverford College. “As long as that is the setup, there’s really not that much that Congress can do about inflation.”

And while economists agree that congressional spending can contribute to inflation, and that at least some of today’s inflation came from the wave of aid that flowed during earlier stages of the coronavirus pandemic, they also said that much of that money’s influence has already played out. The big relief programs passed under the Trump and Biden administrations have largely ended, so federal spending is already shrinking.

Norbert Michel, director of the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives at the libertarian Cato Institute, said most major policy changes that could affect inflation now are unlikely to win enough bipartisan support to pass, and would take time to have an effect.

“Other than maybe very targeted tax increases, which I think there’s very little appetite for, there’s not a lot that Congress can do at this point,” said Alex Arnon, associate director of policy analysis at the Penn Wharton Budget Model, which tracks fiscal policy.

Still, with prices weighing on voters, neither Oz nor Fetterman can ignore the issue. The ideas they’ve offered are often broad outlines rather than specific policies — though Fetterman has provided far more detail than Oz. Economists interviewed for this story said some of the ideas the two are promoting, though, would actually make inflation worse.

Fetterman: Fight ‘corporate greed’

“We need to be ... standing up more against the corporate greed. I think that’s one of the drivers there,” Fetterman said in an interview last week with The Inquirer’s editorial board.

Asked how a senator could fight such greed, Fetterman said he’d use his office to draw attention to the problem. In an August opinion piece he published in the Times Leader in Wilkes-Barre, he also called for prosecuting executives of oil and meatpacking companies “who are artificially driving up prices, gouging consumers at the pump and at the grocery store.”

That stand alarmed the Pennsylvania Chamber of Commerce.

» READ MORE: We sat in on John Fetterman’s endorsement interview. Here’s what he said.

“That’s a very adversarial position to take on an industry that supports thousands of good-paying jobs across the commonwealth,” said Jon Anzur, a spokesperson for the group. The Pennsylvania chamber doesn’t endorse in federal races, but the U.S. Chamber of Commerce is supporting Oz.

Fetterman’s plan for inflation includes cutting taxes for “working people” and stronger “Buy American” provisions.

A Fetterman spokesperson, Joe Calvello, said the lieutenant governor would support, for example, restoring the enhanced child tax credit, worth up to $3,600, that was part of President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion stimulus, dubbed the American Rescue Plan. The credit, which expired after last year, briefly drove a dramatic drop in child poverty.

Fetterman also argues that tightening “Buy American” policies would strengthen U.S. supply chains. “We need to make sure we manufacture more things in Pennsylvania and in America,” he told the editorial board.

Fetterman supported both the stimulus bill and the Inflation Reduction Act, passed by Democrats and signed by Biden this summer, saying, “I’m always going to lean on the side for working Americans.”

The second measure in part targeted drug costs by taking a number of steps to cut what Medicare pays. Oz opposed the law but says on his website that he would battle big drug companies, without saying exactly how.

But prescription drugs are a rare product on which federal policy can have such a direct effect, because Medicare is one of the dominant purchasers. “There’s not that many of those things that Congress can influence,” Bivens said.

And despite its name, analysts doubt the Inflation Reduction Act will have much immediate impact on inflation.

Beyond specific solutions, Fetterman has argued that someone as wealthy as Oz, a celebrity surgeon, can’t relate to how rising prices affect everyday people.

“Dr. Oz doesn’t understand it, he doesn’t even understand shopping,” Fetterman said, referring to Oz’s viral “crudite” grocery store video.

While inflation is widely seen as a political burden on Democrats, the Monmouth poll indicated more Pennsylvanians trusted Fetterman on economic issues than Oz, and far more respondents said Fetterman “understands the concerns of people like you.”

But while Fetterman’s proposed solutions might provide some public benefits, fighting inflation likely isn’t one of them, said Arnon, of Penn.

Tax cuts would give people more money to spend, putting upward pressure on prices, he said, and Buy American clauses could increase costs for businesses, which would also raise prices on consumers.

Oz: What he wouldn’t do

On this issue and others, Oz has said far more about what he wouldn’t do than what he would.

The “economy” page on his website consists of 69 words, all focused on criticizing Biden. He has blasted the the Biden stimulus package as a driver of inflation, and he opposed the Inflation Reduction Act.

“Washington Democrats’ reckless spending has caused gas, groceries and other necessities to skyrocket and become unaffordable for many families,” said a statement from Oz spokesperson Brittany Yanick.

She said Oz would aim to “cut taxes for working families, lower health care costs,” and stop free-spending Biden policies.

But in response to a follow-up question, she offered no details about how Oz would lower health-care costs, or whom exactly he would cut taxes for, other than saying he would focus on “small businesses.”

She pointed to the 2017 tax cuts signed by former President Donald Trump, saying many provisions “unfortunately are set to expire.” (Oz has declined numerous interview requests to discuss his policy views, including an invite from The Inquirer’s editorial board.)

Michel, of Cato, dismissed the idea of calling for lowering health-care costs without specifying how.

“If the plan involves ending subsidies/transfer payments that increase demand, along with reducing regulation that helps increase supply, then that’s a plan,” Michel said. “Otherwise, it’s a headline.”

Mainly Oz takes aim at Fetterman, charging that the Democrat would support more federal spending.

Economists generally agree that pandemic aid under both Trump and Biden contributed to fast-rising prices today. But there’s debate about how much can be chalked up to those bills — or to the Democratic measure specifically. At least some of the U.S. inflation is part of a worldwide rise in prices, the result of an economy that thawed out of pandemic freezes with pent-up demand and rickety supply chains. That created unique conditions as the government sent out a massive money infusion.

The impacts of the aid and the economic situation in which it was delivered are “just inherently difficult to separate,” said Arnon, of Penn.

While Republicans supported early pandemic spending under Trump, they argue that the Democratic package in early 2021 was overkill, and came after the worst economic shocks were subsiding.

Yet without the aid passed by both administrations, several economists argued, there could have been a far slower jobs recovery, and even worse impacts on businesses.

Inflation probably rose faster, Arnon said, but without the aid, “it’s very likely we would have seen a whole bunch of different terrible outcomes.”