John Fetterman’s stroke might not have a huge impact on Pa.’s Senate race, but it has reshaped his political identity

In the homestretch of an extremely tight race, Fetterman is hoping surviving a stroke becomes a way to bolster his relatability — and not his kryptonite.

As John Fetterman and Mehmet Oz prepared to debate in a Harrisburg TV studio, Darryl Carney was busy renovating a two-story house around the corner, favoring his right arm.

“In 2014, I had a major stroke. I’m paralyzed all the way on my left side, and you can’t even tell,” Carney, 63, said. Then he pointed at the studio where the lieutenant governor was set to have the biggest moment of his campaign.

“Fetterman can still do the job. I’m living proof,” he said. “He’ll get my vote.”

Thirty minutes south, Karen Mamrak, 66, was watching the debate in York, hoping it would help her decide whom to support. She disliked that Oz had long lived in New Jersey but wasn’t sure about Fetterman. Mamrak’s dad had a stroke, and she knew how serious they could be. Halfway through the hour, she’d made up her mind.

“I understand that Fetterman feels as though he’s fully capable of being a good senator, but … I don’t think he has, right now, the smoothness,” she said. “He’s not eloquent enough right now to represent us. I’m going to support Oz.”

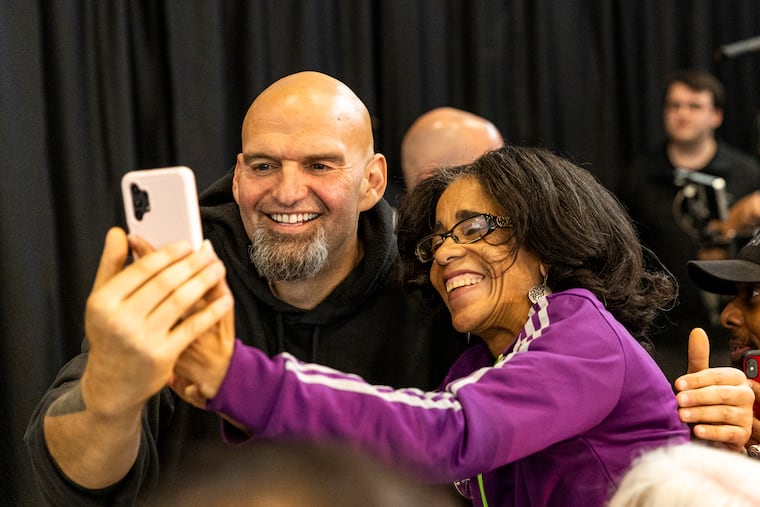

Fetterman built a campaign image as a tough-looking, atypical politician who could relate to voters from Montgomery to Mercer Counties. Since a stroke threatened his life and political career, he’s tried to weave his recovery into that brand, aiming to connect with Pennsylvanians who have faced health challenges by casting himself as a resilient underdog who got “knocked down but got back up.” He’s simultaneously tried to bat back skepticism over whether he’s fit to serve.

“I find it very comforting to find that we’re not alone,” Fetterman told The Inquirer. “A lot of people have told me that they’ve been inspired and grateful to me pushing through. … You can never be confronted with your mortality in such a stark and surprising way to really not have that change your whole identity as a person.”

With days to go until the critical Senate election, polling hasn’t shown the stroke or the debate had much of an effect on voters. But the stroke has had a decided influence in shaping Fetterman’s political identity. And In the homestretch of an extremely tight race, Fetterman is hoping his survival story becomes a way to bolster his relatability — and not his kryptonite.

Concerns about his recovery are far from his lone obstacle. The race has narrowed for myriad reasons, including pushback to President Joe Biden, inflation, and millions of dollars of attack ads on crime.

”The focus on his very serious health challenges in some ways kind of eclipsed the substance of what was going on,” Republican Sen. Pat Toomey said of the debate, arguing Fetterman’s policies are the bigger factor in the race. “John Fetterman certainly comes from the Bernie Sanders wing of the Democratic Party — and that’s not how you get things done, and it’s not the consensus of Pennsylvania.”

From front-runner to underdog

Fetterman cruised to victory in the May primary, winning every single county as his party called him a Democratic unicorn who might have figured out how to win in a year predicted to be tough for traditional Democratic politicians. With his towering frame, bald head, and tattoos, the lieutenant governor benefited from laudatory profiles in national magazines about his 13 years as mayor of Braddock, a small, struggling former steel town outside Pittsburgh.

The stroke came just as he was about to have one of his biggest triumphs on the path toward a job he has eyed since at least 2016. It completely disrupted his plans for the general election, and threw a gigantic wild card into one of the country’s most important elections, and potentially the fate of the Senate.

An early lead evaporated to what is now a dead heat as Fetterman faces the same Democratic headwinds as candidates around the country.

“Regardless of whether Fetterman wins or loses, he will get fewer votes than Josh Shapiro,” Democratic strategist J.J. Balaban said, referring to the Democratic gubernatorial nominee. “There will undoubtedly be a lot of takes about why — was it his tattoos and working-class vibe? His votes on the Board of Pardons? His stroke?”

» READ MORE: John Fetterman had a stroke in May. Here’s what we know about his health.

Balaban thinks that, more than the stroke, the tens of millions of dollars in negative ads were a huge difference-maker, something Shapiro, running against a much-underfunded opponent, did not face.

But the stroke did have a more subtle impact: It kept Fetterman off the campaign trail for three months, unable to deliver on his “every county” strategy. His events, more pep rally than persuasion, had served to motivate his base, though he’s stepped up the pace in the last two months with a busier public schedule at times than Oz.

Despite the race’s tightening, voters appear to view Fetterman more favorably than they view Oz, and voters in a recent poll said he is more understanding of Pennsylvanians’ issues. He’s used that to his advantage, trying to contrast himself with Oz, a celebrity doctor and daytime TV host, for whom a big challenge has been relating to voters.

But Fetterman has had to repeatedly assert that he is physically and cognitively fit to serve. He’s said his only lingering challenge is auditory processing and word retrieval, for which he has relied heavily on closed captioning. The campaign has not provided any doctors to reporters to interview and has faced backlash for initially painting a sunnier picture of Fetterman’s health than turned out to be true.

Even some Democrats have criticized the slow pace at which his campaign released information about his health.

“I think it is more urgent now for the Fetterman team to release more health information about him, to reassure people he’s OK,” Democratic strategist Mustafa Rashed said after the debate. “This should be an impetus to be fully transparent about his health records so people know he’s fit and ready to serve when called.”

‘He’s speaking for me’

Fetterman has pointed to two doctors’ letters along with his appearances at public rallies across the state as the “ultimate transparency.” And his supporters have lauded his public appearances, which still involve frequent stumbles, as brave.

“Every time John Fetterman speaks, he’s not only speaking for himself, he’s speaking for me and millions of other people who are stroke survivors,” said Desiree Whitfield, a stroke survivor from Mount Airy. ”To let us and the world know, just because you’ve had a stroke, doesn’t mean you’re out of the game.”

Fetterman asks supporters at every rally to raise their hands if they’ve had a health challenge, something he says he started spontaneously.

» READ MORE: Everything you need to know about Pa.’s November 2022 election

“I started wanting to connect, like, ’Hey, am I the only person who feels like this sometimes?’” he told The Inquirer.

At a recent endorsement event, Jerome Fordham, an evangelist based in South Philadelphia, greeted Fetterman as a fellow stroke survivor. He talked about having to write down his sermons to make sure he stays on track.

“It does affect you, but you can do your job,” Fordham said. “It’s very relatable what he’s going through, knowing what to say but not always getting it out.”

The connections seem to have resonated beyond stroke survivors in Pennsylvania, where 1 in 4 residents have some type of disability. A Fetterman supporter who’d beaten cancer told a reporter at a Philadelphia rally how they connected with his struggle. A speech pathologist at a rally in Bucks started crying, saying Fetterman reminded her of her students working through communication challenges.

“I think if you look at the electorate, you see that regular people have stroke survivors in their families or in close friendship, or they know people with disabilities or chronic illnesses,” said State Rep Jessica Benham, a disability-rights activist from Western Pennsylvania.

Benham, who is also the first state representative who has autism to serve in the state, didn’t support Fetterman in the primary but called him “1,000 times more relatable now.”

“It’s inspiring and not in the kind of patronizing inspiration-porn way, but in a like ‘I trust this guy to fight for people with disabilities because he gets it.’”

Disability advocates have come to Fetterman’s defense — criticizing media coverage of his campaign and arguing that closed captions are a tool that should be available to those who need them. Neither Fetterman nor Oz has put out any detailed policies or legislation related to disabilities, though Fetterman has said his experience has led him to want to push for better access to health care in rural areas.

‘They handed it to you on a platter’

Fetterman’s very rocky debate performance worried Democrats as it represented the last live impression a lot of voters would have of him before Election Day.

But polls showed little change, likely reflecting that many of the people who tuned in had already made up their mind.

In a recent poll taken after the debate, more voters (48%) believed Fetterman’s assertion that his speaking problems do not affect his ability to think or do his job than disbelieved it (38%), and just 3% of respondents said the debate had them reconsidering their vote.

Still, fewer voters said they saw Fetterman as capable of effectively serving a six-year term (48%) than said the same for Oz (59%).

National Republicans supporting Oz see an opportunity in spotlighting Fetterman’s post-stroke challenges, though. RNC chair Ronna McDaniel commented on a joint appearance between Fetterman and Biden, taking aim at the president’s own verbal struggles, saying, “Well, maybe they can get a full sentence out.” An ad by a super PAC backing Oz shows one of Fetterman’s most difficult debate moments, when he failed to explain why he’d shifted his stance on fracking.

» READ MORE: Mehmet Oz’s Senate run has stripped the gloss off his TV image. That could weigh on him in a tight finish.

“I do support fracking,” Fetterman said, before pausing, then adding, “I support fracking, and I stand, and I do support fracking.”

“They handed it to you on a platter,” Lavern Brown, an Oz supporter, told her candidate at an event the morning after the debate.

Brown told The Inquirer that he wasn’t just talking about Fetterman’s communication challenges, though. He thinks Fetterman has failed to defend against attacks calling him soft on crime in particular.

“Besides the point that he had a stroke — I’m not making fun of that because we’re all gonna have a stroke some day — besides that, he’s just … clueless, and he has the wrong ideas on absolutely everything.”

Fetterman’s use of closed captions has also led to questions about his ability to do the job.

The Senate is not the deliberative body it once was, said Wendy Schiller, a historian and Brown University professor. Senators can rarely offer amendments anymore, she said, but the lack of action in the chamber has made for a more public job outside of it — holding news conferences or interacting with constituents.

“You could see someone saying, if we really want someone who will get attention for what Pennsylvania needs, Mehmet Oz can work the cameras,” Schiller said.

Toomey points to his own work as he stumps for Oz. Every day, he said, he’s on the phone with constituents, colleagues, regulators, and others.

“It’s formal, it’s informal, it’s negotiations, it’s consultation, it’s learning. … This is the majority of what the job is,” Toomey said. “You can feel great sympathy for a guy who suffered a terrible, life-threatening stroke … but also feel like maybe this isn’t the job for him.”

Sen. Bob Casey, the Democrat supporting Fetterman, has argued the opposite.

“John Fetterman is up to the job right now,” Casey said on MSNBC last week.

And Casey and others have said that what Fetterman promises to vote for will matter most, particularly if Pennsylvanians concerned about abortion rights, union rights, and democracy turn out in big numbers. Fetterman got into the race talking about being the 51st vote for Democrats.

“If I were the Fetterman campaign that’s what I would run over and over again,” Schiller said. “At the end of the day, I’ll be the vote that protects labor and health care and women.”

Staff writers Jonathan Tamari and Rita Giordano contributed to this article.